Roller Skating, Civil Rights, and the Wheels Behind Dance Music

This archival feature from Electronic Beats, initially published in 2014, explores rollerskating culture and its relationship to dance music evolution in Chicago and New York City.

Wheels matter for music. From roller skating grooves and the importance of punk, hardcore, and hip-hop for skateboarding to productions tailored specifically to car audio bass—the feeling of freedom that movement from wheels provides has long permeated pop-cultural consciousness.

In the beginning, there was a loop. The history of modern roller skating and its relationship to dance music is one of direction, flow, and repetition: on the most micro level, wheels turn, allowing pivots and limbs to swerve and sway. Zooming out farther, skaters cruise at rinks counter-clockwise in an oval, over and over again, lost in rhythm but always gliding in time to an all-powerful groove laid down by the DJ. However, skating isn’t just defined by a smoothness dictated by the DJ’s predominantly groove- and loop-based music—it has long fed back into the production of dance music that’s as popular outside of the rink as inside.

And yet, within the broader pop-cultural narrative, roller skating, like disco, still receives short shrift as a fad that went out of style with pet rocks. That is, predominantly for white communities. Because roller skating in the United States—specifically “style” skating—has long been a Black American past time. And unbeknownst to most of white America, where roller rinks have long closed down or are used predominantly for “artistic” breakdance and figure skating-like competitions, skate culture in Black communities continues to be as popular today as it ever was. Yet its influence on the development of dance music, from disco, funk, and R&B, to hip-hop, crunk, Miami bass, techno, and later on, footwork, has long gone criminally underdocumented—a glaring omission also reflected in the larger context of academic roller skating histories. In short, skating has been vital to both the evolution of popular American dance and dance music for decades. And to understand why is to understand the remarkable space that it occupies at the very core of American civil rights struggles.

But first, a brief history. In the forties and fifties, roller rinks, like swimming pools, amusement parks, and other spaces of recreation in America, were strongholds of de facto segregation in the North, where the second phase of large scale African American migration from the South had recently come to a close. But unlike the then newly implemented integration of the labor force and the U.S. military, which were guided by the pragmatic color-blindness of American capitalism and militarism, skating rinks were amongst the last bastions of social “leisure” spaces separating white from Black. As historian Victoria Wolcott explains in her singular work connecting roller skating and civil rights history, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in America, co-ed dance and music culture at roller rinks ultimately provoked widespread fear of interracial sexuality: “In sites where leisure was consumed actively and men and women mixed, segregation invariably followed.” This intensified when, at the same time, the introduction of vinyl and the accessibility of record players revolutionized the music that was played in rinks.

In cities like Chicago and Detroit, gaudy tones of the Wurlitzer organ—the familiar hurdy-gurdy-like sound of American amusement—were replaced by early R&B à la Jimmy Forrest, Count Basie, or Duke Ellington. Suddenly, quad skates—an innovation from the original nineteenth-century inline skate design—were being used to their full potential as tools of dance to early groove and swing-based music in African American skate communities. But “Black” skate nights weren’t simply provided by white rink owners in the forties; they were hard-won through civil disobedience. Many of the first sit-ins in America protesting racial inequality were actually “skate-ins,” which took place across the northern United States a good twenty years before the mass mobilization of marchers fighting legal segregation in the South. These included the violent White City Roller Rink protests in Chicago, as well as NAACP-led rallies at the Alhambra Roller Skating Rink in Syracuse, New York, and at Harriet Island Park in St. Paul, Minnesota, amongst numerous others. And while rinks everywhere were transformed into battlegrounds in the fight for equal rights, the result, paradoxically, was often not the integration ideal, with black and white skaters gliding to a new rhythm together, but rather exclusively “Black” nights and “white” nights; or alternately, exclusively “Black” rinks, albeit often with white owners—a phenomenon that persists to this day, much to the chagrin of the African American skate community, and key figures like skate historian Tasha Klusmann.

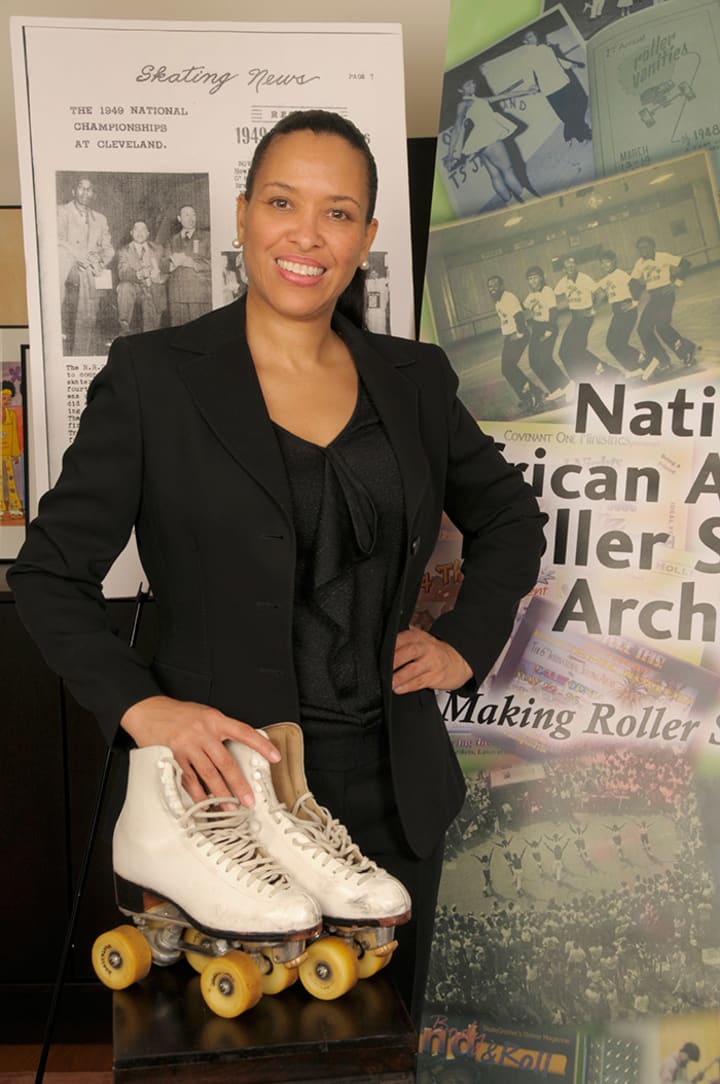

Klusmann, a Washington D.C. native, runs the National African American Roller Skating Archive, housed at the prestigious Howard University, which boasts hundreds of interviews with style skaters and DJs. For her, African American culture is as integral a part of roller skating history as skate history is to African American culture—a position largely ignored by historians of both. Today’s African American style skating communities across the U.S. still regularly experience difficulty in finding rinks to host larger late night “adult” parties—an obvious vestige of a historical struggle. This is also reflected in the usurpation of dance moves pioneered in black skate communities by “jam” skaters celebrated in predominantly white mainstream skate circles. For Klusmann, music and skate style are two sides of the same coin, developed in tandem with the introduction of soul, R&B, funk, and early disco into the rinks. But the marked regional differences in music played in the rinks across the country, from the fifties up through the eighties, were partially a result of the fight for independent African American radio for- mats—that is, in contrast to today’s nationalized generic music conglomerates that control the airwaves.

As she put it, “When I was a teenager, we didn’t have national radio. There were local D.C. radio stations only, so what music we liked might not have been what was going on in Detroit and New York and anyplace else. Every hub had the music it liked, and this was really the case with the black community. For D.C. in the seventies, it was Melvin Lindsey’s original Quiet Storm show on Howard University radio WHUR-FM.” With a few exceptions, notably Amy Reinink’s excellent writing on the D.C. skate scene, and a promising upcoming documentary United Skates by Dyana Winkler and Tina Brown, which focuses more on African American skate culture at large, little has been done on the significant influence of skate culture on dance music.

Ultimately, countless rinks in African American neighborhoods have functioned as veritable petri dishes for the regional development of dance music cultures and were often equipped with separate dancefloors (occasionally “kiddy” discos), where young performers would get their first break, and budding DJs could expand their repertoire on top of playing for the skaters. This story and the following interviews should by no means be considered an exhaustive account of the music inspired by and played for skating’s smooth glide within the rinks’ larger loop. It also shouldn’t be considered a detailed account of the relationship between race, segregation, and style skating. Those each deserve separate books and would have to include cities like Los Angeles, Atlanta, Houston, and St. Louis (amongst others), all of which have big skate scenes and notable musicians born from them.

Nor is the emphasis here on the act of skating or the vibrant scene itself. Instead, this is about the historical foundations of influential dance music sub-cultures. The interviews here are, barring a few notable exceptions, with DJs and producers whose reach in dance music has gone beyond that of the rink to be able to explain the music’s influence outside of it. Here in Part One, the focus will be New York’s original disco and boogie powered style skate explosion and a brief introduction to the birth of the hip-hop groove, as well as Chicago’s reworkings of James Brown and the fever-pitched footwork that developed alongside of it.

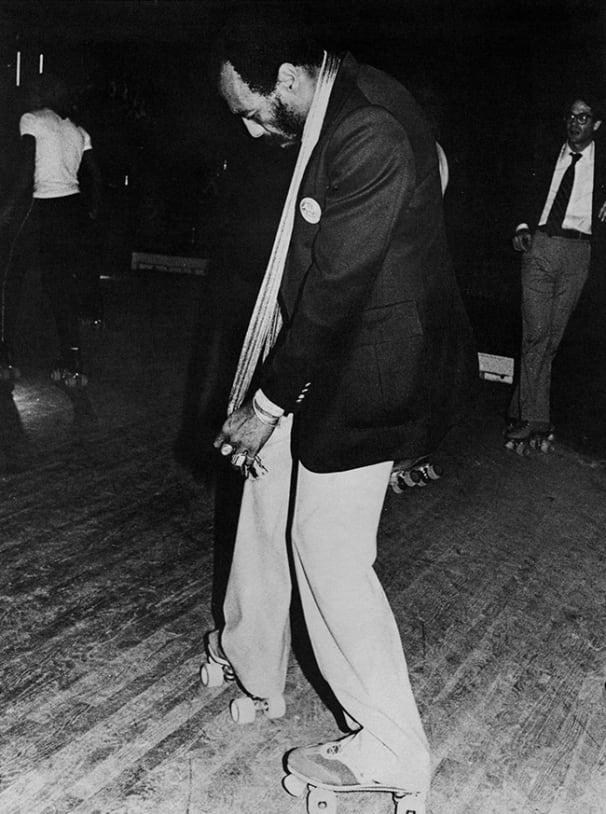

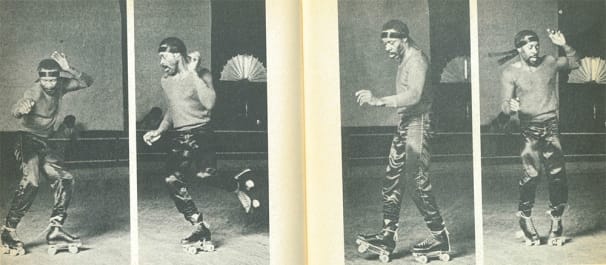

It goes without saying that in dance music history, it doesn’t get much more fertile an environment than New York in the late seventies and early eighties, from which disco, house, and hip-hop would emerge. Empire Roller Rink in Brooklyn is often credited as the nucleus of the funkier, bass-driven skate styles. DJs such as the legendary Robert “Big Bob” Clayton—still an active selector on the national roller skating scene—introduced a disco vibe that matched the utterly original moves previously introduced to the rink by the godfather of style skating, Detroit native Bill Butler. As Butler explained to me recently by telephone from Atlanta, the true revolution in skating at Empire came with his own insistence on introducing the slow groove of Count Basie’s “Night Train” to Empire’s then-primitive sound system in the fifties: “In Detroit, we had to picket to skate a single night because it was an especially segregated city at the time. Then I landed in Brooklyn in 1957 and changed the whole concept of roller skating by introducing Count Basie. Everything after that became skating to the downbeat, and the rest is history. See, space plus the beat equals all strides. I could have been a mechanical engineer, but I chose to roller skate.”

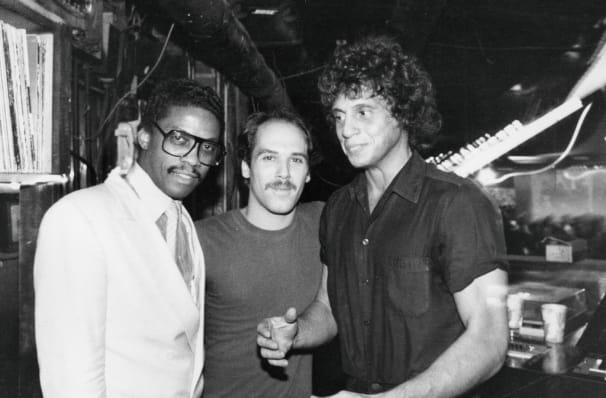

While Butler would go on to develop many of the strides and dance moves that became de rigueur for style skaters in the disco era (documented according to the region in his famous how-to-style skating book Jammin’), Manhattan’s Roxy roller rink would prove to be equally influential in terms of its selectors, amongst whom dance music pioneers DJ Julio and Danny Krivit stood out. Krivit, a DJ, producer, and founder of the legendary 718 Sessions party in New York, sees an enormous and often undiscussed influence of New York’s groove-based skate music styles on much of the disco and post-disco tracks made in the seventies and eighties. As a native New Yorker and a busboy in his father’s legendary West Village cafe, The Ninth Circle, Krivit grew up surrounded by music and musicians who defined various eras in popular music, from childhood friend Nile Rodgers of Chic and neighbor Ian Underwood of The Mothers of Invention to meetings with James Brown. Here, Krivit takes us through style skating’s most defining era in New York dance music:

I roller skated when I was a kid with little metal skates. It was just an activity like any other.

“I certainly didn’t think of going to a roller skating rink, even though they did exist, because at the time rinks that I knew of only played muzak and melodies. It was not rhythm, and certainly nothing with a beat. The rinks back then didn’t encourage that. And ethnic or ‘non-white’ rinks were pretty segregated. But this started to change in the seventies in New York, which is also when certain rinks started to play entirely different music than before. Ultimately, the real change in skating came from when people stopped skating to melody and started skating to the groove. For me, at the center of this was Bill Butler and DJs like Big Bob at the Empire Roller Rink in Brooklyn in the mid-seventies. Around the same time I got my first more serious pair of three hundred dollar skates. Suddenly I could control how I moved, even dance on skates. By ’77 I started seeing that there was a whole skating scene. Then, in the summer of ’79, I DJ’d an outdoor skating party, which is where I met DJ Julio, with whom I would come to DJ with at The Roxy. That was the first time I played just for skaters.

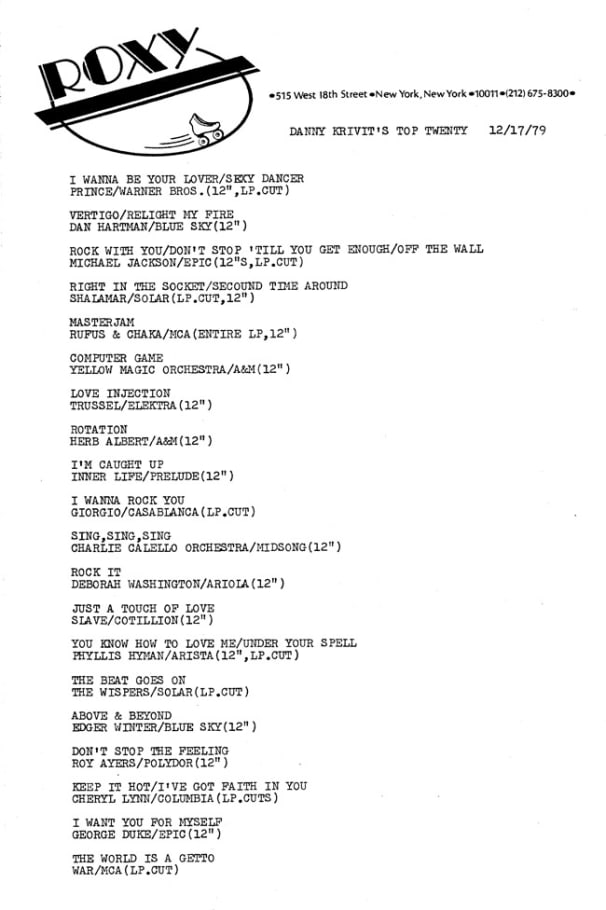

Disco had gotten very strong towards the end of the seventies, but the music also seemed to get a bit whiter and more about the beat than the groove. Even though my style was more soulful and funky and perfect for roller skating, it had me kind of not in the disco trend. I wasn’t playing “Born To Be Alive” but rather B.T. Express. When I played the roller skating gig, it was suddenly much more groove-oriented, much more what I was actually into. And for my mixing style, the skating was also teaching me something: It wasn’t about mixing things only beat on beat, it was more about mixing in the groove. And it was also more downtempo, not as frantic, and not choppy. When I got the opportunity to audition at The Roxy in December 1979, I didn’t think I had much chance of getting the job. I was competing against a lot of the city’s top DJs. But The Roxy was such a huge rink, with the DJ booth way at the far end, and they didn’t have any monitors for the audition, so when you were trying to mix, there was this huge delay and echo on the beat. A lot of the DJs weren’t prepared for that and ended up doing train wreck mixes and also played a lot of inappropriate stuff.

So when I came on, you can see from the things that were in my chart from the same month, like Shalamar, Prince, and Trussel, that I was playing skaters jams. I also knew this element of record store style mixing, which was bringing something in at a very low volume and correcting it on the first or second beat before anyone else really hears anything wrong, and then bringing up the volume and completing the mix correctly. The owner of Roxy, Steven Greenberg, told me I was the main DJ Julio, who was an established roller skating DJ already at the Metropolis, was also in.

Steven was not an easy person to work for, but I made it through to the next owner, also named Steve, who owned another slightly larger rink in Long Island called Laces, where I also got a job and remained there as their main DJ for ten years. Some weeks I’d DJ seven nights a week, but I always played for skaters at least two nights a week. It was a very different scene than club music, but the roller skating groove seemed very natural to me and grounded me musically. The end of 1979 was the height of the “disco sucks” period. Around the same time I started to play at Roxy for skaters, most clubs were fleeing from disco, but they didn’t know what to replace it with. New wave was the first replacement choice, but it didn’t really stick. Then there was freestyle, and eventually, people thought, “Maybe we can get into rap,” but it was still too early for that. That’s about when house music slipped in, kind of a raw stripped-down version of disco. While this was all happening, roller skating was still really strong, and there’s something about roller skating music that was a hybrid of the best things about disco and radio R&B, like a clubbier version of radio R&B.

There's something about roller skating music that was a hybrid of the best things about disco and radio R&B, like a clubbier version of radio R&B.

Roller skating music was also starting to refine itself. A good example of that is “Give Me The Night” by George Benson. If you listen to it closely when you’re skating, you’ll notice that instead of having an emphasis on every other beat, there’s a clap every eighth or sixteenth beat. It’s where you would push with one foot on the other emphasis, which was the ideal skating groove. Of course, there were more high energy or downtempo grooves, but this was in the pocket, and a lot of music made at the time was right there. A lot of producers and bands didn’t necessarily want to admit that some of the music they made was particularly for skating, while you had other songs that were explicitly about skating, which was kind of ironic, as they didn’t fit into the real skate groove at all. You had this movie Roller Boogie, and they pushed Earth Wind and Fire’s “Boogie Wonderland” as this roller skating song, and when you saw people skating to that, there was no larger rhythm. It was as if everyone had headphones on skating to a different beat! On the other hand, something like Vaughan Mason’s “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll” worked really well. At the time, I was in a DJ record pool, and we would also go to record companies for records. My friend Bobby Shaw was at Warner Brothers, and we were always going to his office to get new records on Fridays. He had a lot of key releases for roller skating, like “Are You For Real” by Deodato, “Love X Love” and “Give Me the Night” by George Benson, “More Bounce To The Ounce” by Zapp. The group of DJs that gathered in the office were a lot more R&B oriented like myself, and half of them would show up in the rink regularly. Also, in the beginning of the eighties, a lot of people were looking at the dance charts and thinking that something weird was happening, because the top dance songs charted seemed to have no relationship to sales. In contrast, the R&B charts were directly related to sales.

To me, it seemed like there was an entire hip-hop scene around picking the skate grooves.

“The next week he’s playing the song, Frankie Crocker from WBLS hears it, it hits radio and becomes a massive hit. Of course, Tee Scott’s remixes were also huge for skating, and there was another very strong overlap there between the club and the rink.”

From the rink to the dancefloor: DJ Spinn & RP Boo

It’s also in Chicago’s various roller rinks where footwork, one of most celebrated electronic music and dance movements to appear in recent years, was born. Many of footwork’s first dance battles took place after participants took off their skates, and it’s no secret that late footwork pioneer DJ Rashad and long-time friend DJ Spinn met at the Markham Roller Rink in the city’s south suburbs. Here, DJ Spinn, himself a former rink DJ, and footwork legend RP Boo explain the strong link between the development of footwork and Chicago’s JB skating.

RP Boo: I first started producing music after I was already DJing. See, I was in House-O-Matic dance crew. I did so-called “performance tapes,” which were made specifically for their dance routines. One day I met DJ Slugo at a party and the president of House-O-Matic wanted to go make a track there with him at Slugo’s house, so we went over, and when I saw what he had to make tracks with, I was surprised: a Roland R-70 drum machine and a Pioneer sampler. That’s it. And he made a track in minutes. I asked him, “Is it that easy?” And he was like, “Yes!” I had just gotten a job at Chuck E. Cheese’s and had some money, so I went and picked up my first R-70. At the time, I was making house, ghetto house.

This article was published in Electronic Beats’ winter 2014/2015 print edition

Published February 04, 2021. Words by A.J. Samuels.

Follow @electronicbeats