How Avant-Garde Designer Ximon Lee Fuses His Transcendental Club Moments Into Gender-Fluid Clothing

It's no secret that the fashion industry plagiarizes club aesthetics. That's why Lee uses responsible design in his work to protect the subculture's authenticity.

Ximon Lee describes his first authentic clubbing experience as a “dark hole you enter” that led to somewhere “ambiguous between life and death.” The cavernous maw he recounts was Griessmuehle, the beloved—and unabashedly ragtag—Neukölln, Berlin venue that closed earlier this year. But in 2015, Lee, an avant-garde fashion designer who was in town post-Paris Fashion Week, witnessed it in full swing. Lee remembers descending down its rickety stairs: “Are they going to fall apart or not?” he pondered to himself. “How is it even possible that this place exists in Germany—a first-world country with the most careful, the most precise, and the most disciplined culture?” Lee himself was born in the border province between Russia and China and has lived all over China, so the confusion he felt questioning the incongruities of this Western adult playground that sprawled before him proved to make an indelible impression on his creative world.

It’s not even that clubbing itself, per se, is the main touchstone for Ximon Lee’s fashion designs—in fact, not at all. Rather, it’s the general dissonant atmosphere that captured his attention that fateful night that continues to nebulously shroud his collections since he moved to Berlin in 2016. Before he relocated, Lee had already built up a reputation for himself in New York after graduating from Parsons School of Design, whose esteemed Fashion Design B.F.A. has churned out the likes of Tom Ford and Alexander Wang. His resume practically glints with its list of polished accolades: Parsons Menswear Designer of the Year award, semi-finalist for the 2014 Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy Prize, the first menswear designer to win the H&M Design Award, and sponsorships by GQ. In 2016, Kanye West declared that Lee was “killing it” at the LVMH prize opening—a statement that has given Lee the kind of immediate pop culture clout designers several years his senior can only dream of.

Yet, in spite of the mainstream recognition, an inquiry into his collections illustrates a distinctly music-subcultural underpinning. For his eponymous brand’s AW18 showcase, Lee conceptualized an interdisciplinary project complete with opera singers and dancers, titled “Masters of Mess,” with Berlin-based producer and performance artist Pan Daijing after a casual meeting through the city’s creative community. The most striking garments within the collection were his red and orange knitwear pieces, which look like oriental rug deconstructions with wavering, greyish-blue vessels compressing and sinewing themselves around their models. Two years later, for his SS20 “Reconscious” collection, Lee tapped L.I.E.S Taiwanese techno affiliate Tzusing to conceive of the runway soundtrack. He’d first heard Tzusing at ALL club; his set was one of the first times in Shanghai when Lee danced until he broke a sweat, so he took a mental note of the DJ’s name for a future collaboration. The final presentation itself contained bibs and overcoats with grainy black-and-white relief prints of nude bodies colliding in space.

Those who go out will immediately infer the clubbing motifs that seem so apparent throughout his work. Its gender fluidity, chainmail shirts, and silver metal hardware (with strategic placements on the body that replicate the look of an industrial piercing) all point to this. However, Lee has a curious way of evading the rave aesthetics that seem so conspicuous to the rest of us: “A lot of things are just not so easily articulated in words,” he says. “It often tends to be misleading or too much of a definition for the product, than actually allowing people to imagine themself the way they want to imagine them.” While this is true, he does admit to perhaps the more subliminal effects of the dancefloor on his design decisions. How can a city steeped in such a bacchanalian energy not assert its influence on its creative inhabitants? “For me, it was not so conscious, but people can feel it,” he says. “People can see.”

About six months ago, Lee witnessed a DJ set by Silent Servant, which would end up animating his imagination in unexpected ways. What he remembers taking away were these abstracted images like “massive groups of elephants tumbling around,” “traveling through certain landscapes,” or “race cars with trains” and bygone mental states that seemed to involuntarily filter through his mind. “You’re taking a real experience of certain violence from a sound and triggering some sort of brutal, melancholic memory from your childhood,” he explained. In the past, Lee has used his craft to meditate on themes of hardness and shame, so inspiration, for him, is often an exploration of psychological gradations.

These emotional triggers aren’t the only thing that lead to inspiration. For Lee, it’s about negotiating an entire nexus of the nocturnal experience from “a very socialist building with a very strange, very tacky color combination, to a leather guy with very specific stitching detail, to a very particular latex smell in certain club settings.” Here, he says, “You can see all kinds of behaviors, either freaky or beautiful, powerful or very relaxed. You can see all kinds of body movements, and that also creates a very interesting reference in what you’d think about silhouettes.”

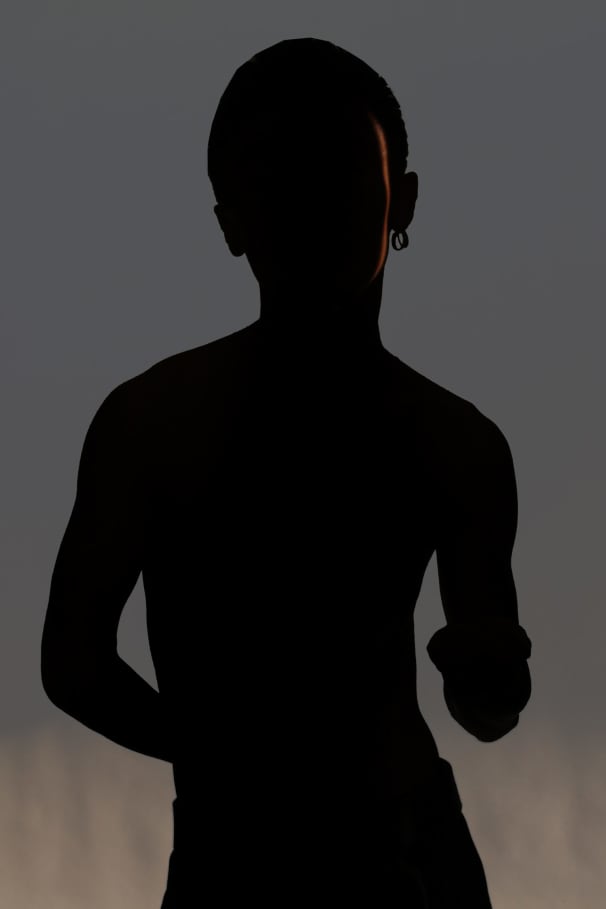

The silhouette itself, through the way that the shadow maintains its amorphousness while still insinuating the human form, is an apt metaphor for the way club culture works its way into Lee’s designs. “The brand itself was never drawing direct inspiration from sportswear or homosexuality or hyper masculinity or urban cool or the techno dance floor,” he insists. In his business, he explains to me, it’s often easier to drive sales if consumers can comprehend a cut-and-copy of tailoring or logo styles from familiar throwback films or music genres. That’s why, he explains, “a lot of time it’s more about focusing on the material surfaces and the sensibility, rather than some very direct, very obvious things.”

It seems that fashion design, in Lee’s opinion, should function something like an elusive dress code at the world’s most notorious club: It isn’t as blatant as simply dressing in all black. Functionality, wearability, and texture are what signal one’s nightlife affiliation, rather than obvious aesthetic cues. “You can embed [a reference] in a collection and some people will feel the same way as you, as if they’ve also been through this, but it shouldn’t be in your face,” he explains. The dangers involved with the trendy plagiarism of fashion, especially when it comes to co-oping rave culture, is that clothing becomes a highly aestheticized, superficial affiliation, divorced from the themes of community and sonic empowerment the milieu was originally founded on.

This, Lee argues, demonstrates the dichotomy between responsible and irresponsible design. “On one hand [direct referencing] is a completely wasteful practice during development and irresponsible design, but it’s also exploiting a certain subculture,” he says, continuing, “For [the subculture], it’s authentic. They feel that way at the time and they dress in a way that belongs to them. To turn that into a mega-trend or super-popular top seller, you kill that cool. People will no longer want to dress that way because you, as a brand, already killed that; you take the authenticity out of its original context. And, for me, that’s a very uncomfortable thing to do.”

Club culture, in spite of what runway trends will have the masses believe, is not a costume. It’s a living, breathing, and shifting system of political beliefs and social behaviors that also happens to be represented by a dress code. By protecting the aesthetic parameters of a subculture from appropriation through his personal practice, Lee—whether he’ll admit to it or not—betrays his own allegiance.

At the moment, Lee is considering virtual fashion shows. Our interview takes place during the final weeks of Berlin’s lockdown, and the fate of his industry is still unforeseeable. But considering the steady rise of eCommerce, in tandem with the waste of foam boards, plastic, and carbon emissions that involves flying editors into town for a twenty-minute runway presentation, along with rumors of a second COVID-19 wave, a shift towards online is certainly the most viable option. Plus, it’s much easier for a buyer to screenshot a look into a desktop folder than scroll back through an iPhone video, he adds. For clubbing, however, “you can never get it back when you don’t experience it in person and really immerse yourself in it,” he observes. “I’m not sure how the future will be. But I think nightlife, it’s irreplaceable.”

Whitney Wei is the Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Beats. Follow her on Instagram here.

Published May 22, 2020. Words by Whitney Wei, photos by Luis Alberto Rodriguez, Ronald Rose & XIMONLEE.