Roller Skating and the Birth of Miami Bass and Memphis Crunk

Sound in Motion Part 2: The Role of the Rink in Miami Bass, Memphis Crunk and Baltimore Snap

Essays and interviews by A.J. Samuels

In our four-part series Sound in Motion, we take a look at wheel-based subcultures that have had an especially important relationship to the development of musical subgenres. It goes without saying that ideas surrounding the rolling and cruising experience—from roller skating grooves and the importance of punk, hardcore and hip-hop for skateboarding, to productions tailored specifically to car audio bass—have long permeated pop cultural consciousness. Wheels matter for music, and we’d like to find out how much. Here’s another look at how sound and motion have fed back into each other in the past and continue to do so today.

Part 1 of our roller skating special mapped out the historical conditions that led to African-American roller skating communities developing into petri dishes for some of the most important strains of American dance music. Using the role rinks played in some of America’s earliest civil rights battles as a point of departure, I analyzed how the simultaneous replacement of organs with record players in roller rinks became the revolutionary musical motor behind a new African-American skate experience. With the more “sexualized” genres of jazz and blues now defining how revelers rolled, white fear of interracial mingling increased. Hard won access to rinks by African-American protesters would ultimately give way to the unofficial separation of “black” and “white” nights, which still exists to this day.

Fatefully however, this also led to rinks becoming central stages for music and entertainment in black communities across America, with regional and cultural insularity leading to the pioneering of unique dance music cultures, from early hip-hop in New York City to Chicago footwork, Miami bass and crunk in Memphis—all born in and around skate grooves. But what about the most obvious form of roller skating music—songs about skating itself? During the height of the roller disco craze in the late ’70s and early ’80s, the “thematic” roller skate song underwent a curious evolution, essentially mimicking the disco and boogie tracks already popular in rinks but changing the lyrics so that people really got the skate-themed message and bought the record. Often, however, that tended to miss the point, because while style skaters rely on vocal cues (as both National African American Roller Skate Archives historian Tasha Klusmann explained to me recently and the Bmore club legend DJ KW Griff analyzes in this piece), it’s essentially the rhythm section that defines the essence of skate music, with vocals functioning predominantly as punctuation. But nobody told that to Hollywood and major labels.

Indeed, from Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times and The Rink to Gene Kelly in It’s Only Fair Weather, Hollywood has a long and interesting history of featuring roller skating as a kind of vaudevillian dance element (which it once was). But the film industry’s first serious attempts to cash in on the disco skate fad were with the ultra tacky rom-drams Roller Boogie and Skatetown USA (1979), both of which included similar soundtracks of up-tempo discopop, rock and whitewashed skate-themed songs, e.g. Dave Mason’s “Skatetown U.S.A.,” Cher’s “Hell on Wheels,” Bob Esty’s “The Roller Boogie,” etc. Unsurprisingly, neither the films nor the music caught on in African-American skate communities, though you could argue that they weren’t the target audience considering their West Coast, partially outdoor skate scene focus.

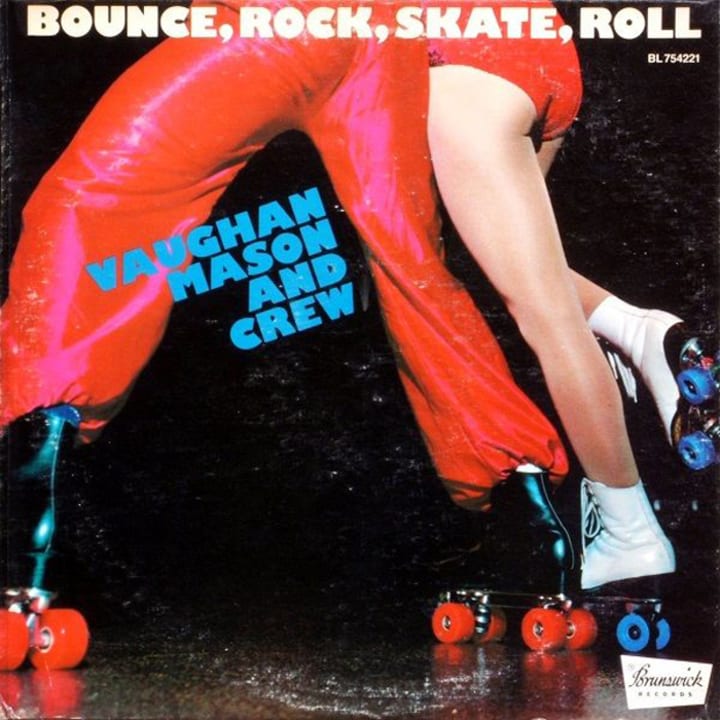

Either way, both were undeniably rife with cultural appropriation. And yet, Hollywood’s and major labels’ failures had little to do with a lack of authenticity in their product, per se, as the handful of thematic skate jams successful in African-American communities were created by opportunistic musicians attempting to cash in on a fad. It’s just that their results ended up funky. As Vaughan Mason recently told me in a lively phone interview from his home in Baltimore (which you can read in full here), his greatest roller skating hits emerged from pure capitalistic moxy:

“So, I’m working at a stereo store on Trinity Place, about four or five blocks down from the World Trade Center. This is the summer of 1979. I was living on my friend’s couch, and I was making about $125 a week. A friend of mine from Yonkers had just graduated from the Wharton school of business in Pennsylvania, and was telling me about stocks and explaining how money works and all that. He said, ‘Why don’t you just get a Wall Street Journal and watch some penny stocks?’ So here I am riding the subway from Brooklyn to Manhattan. On the front of the Journal there was an article that said the industry is selling 300,000 pairs of roller skates a month. I said, ‘There’s no way I can go wrong writing a song about roller skating!’”

The result was “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll.” Indeed, the lure of scoring a skate hit caught on amongst a variety of artists: The late ’70s incarnation of classic doo-wop combo Little Anthony and The Imperials had some success with their skate anthem “Fast Freddie the Roller Disco King,” which featured none other than a young Prince (a known roller skating obsessive) on electric guitar—not that they followed up on it. Other more dubious figures also tried their hand at the rink burner, including the jailed former cult leader and controversial Afrocentric author, Dr. York. His funky, slightly upbeat Afro-disco skate gem “Shake ‘n’ Skate” from 1981 found a place in sets of African American style skate DJs in the north eastern United States—that is, long before his writings expounding on the evils of the Illuminati were popularized by early ’90s rap luminaries like Mobb Deep. Regional hits like Michigan Avenue’s “Roller Skate Cowboy” or Times Square’s “You’re Hot” were groovy outliers for skating communities that made smalltime artists and managers a quick buck, and there were countless others. What many have in common—in contrast to the faster disco-oriented major label fodder—is that they are more like skate “dubs,” groove copies in a sense, with “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll” being the best example. Think Chic’s “Good Times” and multiply that by X, with the minor exception being a handful of electro-inspired skate tracks in the early-mid ’80s.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QKqdcGX80JE

Inevitably, Hollywood would eventually revisit roller skating, this time in an attempt to appeal to today’s sizeable African-American skate scene amidst a spate of appearances in the mid-2000s by jam skaters in music videos for the likes of Ciara and Missy Elliot, amongst others. However, some style skaters had mixed feelings about films such as 2005’s retro skate flick Roll Bounce starring Bow Wow or 2006’s rink drama ATL, starring Atlanta rapper T.I. and Outkast’s Big Boi, and coproduced by TLC’s T-Boz. The latter is based on the significant hip-hop scene surrounding the historical Jellybeans roller rink in Atlanta, where groups such as Outkast, Goodie Mob, TLC, hitmakers Dallas Austin and Jermaine Dupri all hung out and skated in the ’80s. For historian Tasha Klusmann, both films come across as somewhat inauthentic representations of the style skate scene, despite the attention paid to detail in the skate choreography.

In contrast, national skate party promoters like Donte Doyle see the increased coverage of African-American style skate scenes as a positive development, regardless of the accuracy of Hollywood’s dramatizations. A style skate entrepreneur of sorts, Doyle has invited stars like Bow Wow to make appearances as guest MCs at his skate parties, such as the recent Skate Warz held in Orlando this past November. Musically however, Doyle seemed adamant when I spoke to him about sticking to rink specialists as DJs. And for good reason, as skaters from all over the U.S. travel to national parties expecting skate DJs to know the rink diaspora’s musical common denominators, as well as understand the different kinds of music played in regional African-American style skate communities: JBs in Chicago; slower R&B grooves for Baltimore style “snap” skaters; Bmore and Philly club for “fast backwards” skaters from New Jersey; house, boogie and disco classics for the New York heads. In that sense, Moodymann’s Detroit-based Soul Skate—often the lone style skate party discussed in dance music circles—is actually something of an anomaly within the national style skate scene, it being pretty much the only time of year when skaters also roll to big name acts like “Little” Louie Vega or DJ Quik, as opposed to national party DJ regulars like Brooklyn’s beloved DJ Arson or Chicago’s DJ Joe Bowen.

That said, Part 2 of Sound in Motion will continue to focus on important American DJs and producers who not only started out in rinks, but made some of their most significant musical contributions in them—both in terms of sound and accompanying dance styles. Read on about how these artist’s genre-defining contributions to music were influenced by the groove and smooth, circular roll of one of America’s most underappreciated wheel-based subcultures.

Roll the Bass: Luther Campbell on the Importance of Miami’s Roller Rinks.

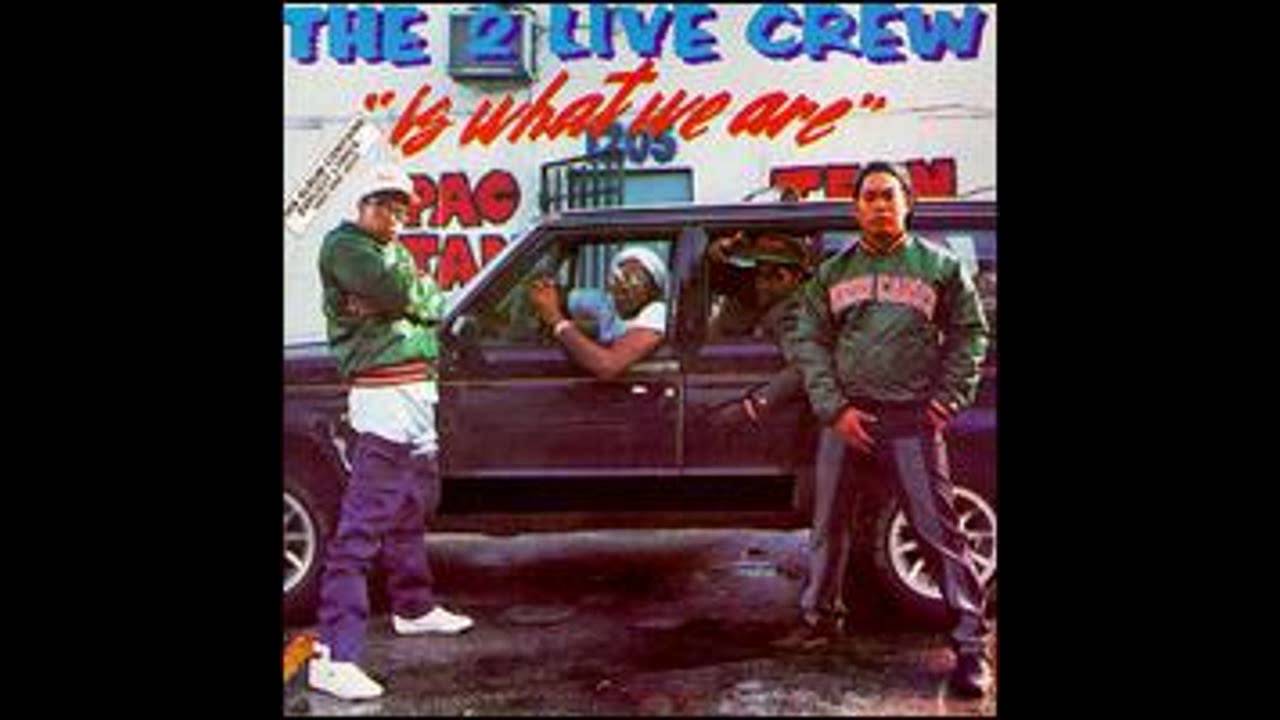

To say that Luther Campbell holds a special place in the history of rap music is an understatement, particularly in regards to the larger role he has played in American popular culture. As the musical mastermind behind legendary rap group 2 Live Crew, the South Florida native helped establish the legal precedence of not one but two separate cases of free speech (obscenity and copyright, respectively) that went to the United States Supreme Court. Which is to say the 54-year-old former candidate for mayor of Miami has done more to defend artists’ rights than all the music power lawyers and petabytes of online petitions combined.

But before that, Campbell was known as one of the founding fathers of Miami bass, the southern electro-funk subgenre pioneered in the early ’80s and devoted to the idollike worship of low frequencies. With his Ghetto Style DJs crew, he made a name for himself battling other Miami sound systems in rented out roller rinks, holding some of the city’s first ever bass parties. It was in the rink that Campbell would first tailor his booming, freshly pressed, 808-driven productions to the moves of skaters and dancers alike.

Campbell’s time spent in roller rinks was not uncommon for Miami bass producers. Fellow innovators and rink DJs Maggotron and Magic Mike both emphasized in separate interviews the importance of the rink as a starting point in their respective DJ careers, although neither seemed especially inspired by the skating experience. Campbell, however, spoke passionately about how the rink fed back into the music, sensing the power of controlling both the dances and the skate speeds during his legendary Pac Jam parties at Sunshine Skateway and, later, Superstar Rollertech, together with freestyle music legend Pretty Tony and his Party Style DJs crew. Here, he describes how many of Miami bass’s dances were created in the rink and how skaters responded to the low end.

Luther Campbell: Skating was a big part of our childhood growing up. When I was about eight years old, I can remember my parents bought me these Union 5 skates, which we strapped on to our shoes. This is some deep down south history, right here. At Hadley Park, on Christmas day, we put on a pair of Levis and a pair of skates and would actually skate around the outside of the local rink. Then we would move on to my elementary school, which we used as an obstacle course: You’d hop over the fence, go down a big hill, climb up some more stairs, hit the corner and crash hard because you played hard. And that is what prepared us to go into the white neighborhoods with our sound systems on Sundays.

The first time I ever played inside for skaters was at the Sunshine Skateway in Homestead, which is out in the suburbs. This was in the early ’80s and back then, like today, Miami was a very diverse place. I’m from Liberty City, which is about as far as you can get from the suburbs. At the time, not very many rinks let real DJs into the premises, especially African-American DJs, because the rinks around here were predominantly white. But on Sundays, when the rink was supposedly closed and the white kids were off doing their thing somewhere else, that’s when they let us in to do our thing.

This is when we started putting on our first real bass parties for skaters at 199th St. and Rt. 441 in Ft. Lauderdale, which was Gold Coast skating rink. We dubbed the party Pac Jam, which was named after the teen disco that I had. The title was essentially our slogan: our jams were always packed. The rink owners would be making tons of money when the places were filled with black kids. And for a lot of the people at the party who were from black neighborhoods like Liberty City and Overtown, it was like going out of town for us. But eventually white residents started complaining about all the black people coming to their neighborhoods. It was all kinds of political bullshit.

One of the unique things about my party and my crew was that we would create dances. In fact, a lot of the party was about that in particular. The very first dance was the Ghetto Jump, which we invented, though we never received credit for the track that came later. But that’s another story. See, the parties were so full that we organized it so that people would dance in the middle of the rink, while others skated all along the outside. And along the sides of the rink before you actually got onto the floor, people were dancing as well. Ghetto Jump had the whole rink jumping in the air and doing crazy things with their legs. Then we had the Throw the D and Throw the P, which was named after the song that we had at the time with 2 Live Crew and my Ghetto Style DJs crew. At the time, all the dances were done both on skates, in skating groups and with the skates off, as well.

What we brought to the rink was a total change of music. This also included the concerts we had there. And the music that we brought to the rink wasn’t yet Miami bass. Rather, I created Miami bass in the skating rink. But there was a lot of electro, hip-hop, Herbie Hancock, Egyptian Lover, Mantronix, sometimes slowed-down, dragging, bass-heavy Kraftwerk and Original Concept. Then there were the real slow jams for couples skating. And there were so many creative skate crews.

But in the last hour we always had people take off the skates and turn it into a big ass dance party. Importantly, you always had to tailor the music to people with skates on and skates off. With Throw the P, Throw the D and Ghetto Jump you could do all that, and they were all created in rinks for that very reason. What many people don’t understand is that we wanted everyone to be able to skate to the music because skating’s a large part of our history. And the rinks were where our clientele was. This was always taken into serious consideration when DJing and making music. When I discovered 2 Live Crew, it was when I brought them down to perform in a skating rink. The music was fast and electronic. ‘Beatbox,’ for example, was perfect to speed skaters up. They would hit the corners hard as hell, with fast tricks. To the slow tracks people were doing real nasty dances along the walls of the rink.

The last rink where Ghetto Style DJs played was Superstar Rollertech on 79th Street, which is where I actually first saw New Edition. They built a stage in there from the beginning, which made it an important part of young, black music culture in Miami. Pretty Tony Butler used to DJ there, and it was owned by football players Nat Moore and Larry Little. It was the first African-American skating rink in South Florida, and Pretty Tony did a great job with the parties at first. In the beginning lines were around the corner. But the violence destroyed everything. When they started losing money, we were called in to help. Not long after, gangs started taking over with shootouts and fights. Of course, Pretty Tony is a great producer and the music he put out on his label Music Specialists is fantastic. He’s the first person I brought 2 Live Crew to to see if he wanted to put out our record, but he turned it down. We used to have legendary battles with his crew Party Down DJs and Disco Rick, who now runs the famous King of Diamonds strip club. In Miami, all this stuff is connected.”

From Bmore Club to Snap Style Skating: KW Griff on How Rinks Keep the Groove Alive

While in cities like Miami and Memphis many skate moves were emulated on the dance floor after the skates came off, in Washington D.C. and Baltimore, “snap” skating to quiet storm and rare R&B B-sides is pretty much impossible to simulate without wheels. The fast, smooth, inside-outside leg movements have long been the region’s signature style—one which only increases in speed as the music gets slower. Recently, rare groove skate classics have gotten a production update from an unlikely direction, namely Baltimore club legend KW Griff. Baltimore club DJs are, however, no strangers to skating, as fellow club icon Scottie B famously got his start in the city’s now closed Rhythm Skate rink.

Not long ago, Griff’s club classic “Bring in The Katz” was rereleased by Night Slugs, though Baltimore’s mid-tempo breakbeat sound has taken a back seat to much of the music it’s helped spawn, namely younger (and currently hipper) siblings Jersey and Philly club. Meanwhile, Griff has become increasingly interested in skate music production, following an epiphany of sorts in connecting the rare groove records played in rinks and the many obscure R&B cuts in his own massive collection as a radio DJ. Here, he explains his fascination with the Baltimore skate groove, what his production tweaks have done to renew Baltimore’s rink soundtracks and how he came to DJ at the renowned Shake & Bake and Hot Skates roller rinks.

KW Griff: My skating experience growing up was occasional. As a teenager I was mainly going to Rosedale, Columbia and Rhythm Skate, and in those rinks, for the sessions I was attending, they were playing more up-tempo dance and electro—Afrika Bambaataa & Soul Sonic Force’s ‘Planet Rock,’ Newcleus’s ‘Jam On It,’ etc. So that’s what I actually thought skating was all about musically until in later years when I started venturing out and experiencing what was going on in other rinks. Even back then in Baltimore and some of the surrounding areas, it was clear that different rinks played different types of music during different sessions.

Around 2001 is when I started paying attention to music more in the 80, 90 BPM range, which is what skaters in the DMV—District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia—consider their speed for ‘snap’ skating. It’s a smooth but fast type of roll around the rink. It’s not a dance style of skating; there’s no stopping in the middle of a stride and spinning around and all that fancy stuff. DMV snap skaters may do a few little tricks in the middle of the floor but usually it’s a continuous motion around the rink because more than anything it’s about flow. So, around the early 2000s, a friend of mine asked me to stop down at Shake & Bake with him.

When I went inside, it was an ‘adult’ evening session and they were playing music I was very surprised to hear: rare George Duke and Barry White B-sides that are obscure to most but classic in certain circles. I had no idea that people skated to this. You see, when some people think of Barry White they think of ‘It’s Ecstasy When You Lay Down Next To Me’ or other hits. But what I heard at the rink wasn’t familiar to the average radio listener, and I had some of these albums. Eventually that led me to become more involved with skating again and, over time, to make roller skating tracks of my own.

In making roller skating tracks I take a similar approach to my Baltimore club adaption of ‘Foot Stompin’’: I use these B-side classics, but I don’t really change the essence of the songs. All I want to do is give it a little more bump, adding a few bells and whistles to make it a bit stronger with more hard-edged type beats so it would appeal to younger skaters without taking away what the seasoned skaters enjoy. It’s somewhat similar to, for example, what producer ShaProStyle from Chicago does with James Brown-inspired tracks, although I didn’t know of ShaPro at the time.

It’s actually at some of the national parties during ‘roll call,’ when every state has a certain period of time to just go out on the floor and represent their hometown style of skating, that I got to learn about the other types of music that other regions like to skate to. There I discovered the bridge between Baltimore club and skating—that is, other than my skate dub edit of I-Roc-T’s ‘Work Your Body.’

For example, North Jersey and Philadelphia ‘fast backwards’ skaters roll to some of the Baltimore club tracks. They basically do it in trio ‘trains’ in reverse along the wall. A lot of the trio music is more upbeat, in the 100 BPM range and higher. It’s interesting to me that the DMV skaters you may have seen at the national party last week rolling to house and showing all their different styles and dances and spins, only want to snap to smooth R&B like Barry White and Johnny Gill at home. Which brings me to DMV crowds. Since I started DJing at Shake & Bake and Hot Skates in Baltimore I’ve noticed how the snap skaters appreciate it when you pay attention to their body language.

That’s also what gives you an idea of whether a song works or not, because skaters won’t even have to say anything to you. The body language and vibe of the crowd will tell you. Which is why when I’m listening to different types of music, I’m thinking, ‘This could be skate-able but it doesn’t have the snares in the right places so it’ll throw them off, but maybe if I redo it I can make it work.’

Actually, as a producer, that’s how I listen to a lot of music. Take for instance, Diana Ross’s ‘Love Hangover,’ the remix of which for the rink I call ‘Skate Hangover.’ If you listen to the original it would be awkward to skate to because it starts off with a down-tempo interlude in the beginning and then eventually speeds up to a disco pace. I knew it had skate potential, it just needed a bit of tweaking to give it more of a skate appeal. And that’s a good example of how a lot of fascinating remixes you really wouldn’t hear anywhere else but the rink. Back in the day, the classic B-side cuts could only be heard at the rink because at that time only the DJs had them. You would go to the rink because you’d be excited to hear these songs specifically. They weren’t on the radio and they weren’t blasting at parties because it’s not really party-type music like, say, Stephanie Mills’ ‘Starlight.’

And that’s what’s special about the vibe in the skate context: It doesn’t matter how many times skaters hear it, they will skate to it. And when they skate, they’re often focused on the song specifically, so they don’t want you as a DJ to mess with it as it’s playing. And I’ve learned that the hard way. Many skaters don’t mind the DJ showing some creativity, but don’t go overboard with excessive scratching, over blending, or cutting songs short, because skating to music is like an art.

Take George Duke’s ‘Starting Again’: That’s a prime example where it starts off smooth and gradually builds to a peak almost near the end of the record. If you cut the song too short or don’t let it play out, there’s going to be some upset skaters on the floor. All they want you to do is play the song, plain and simple. Skaters know what part they’re going to skate hardest to, what part they’ll cool down to, and what part they’ll do a specific move to. Also, skaters love to see the DJ involved and enjoying what they’re doing. You have to imagine yourself out there on that floor and ask yourself, ‘What would I want to hear?’

Baltimore is known for the skaters to roll at 100 miles an hour, as people say. They’ll be in stride going around really fast, but totally smooth. Snap skaters even roll at high speeds to slow jams when they’re skating in pairs during ‘couples,’ and it amazes a lot of skaters from elsewhere because when you think of slow jams, you think of skating with somebody low speed, doing a little Fred Astaire step or just a slow dance where people happen to have skates on. Not in Baltimore. Here, when you put on slow jams around 60 to 75 BPM like Chanté Moore’s ‘Listen To My Song,’ all you see are people whizzing by you. It just reinforces that if you’re not really in the skate world, you don’t know what’s going on. But as a producer and skater, to me it has a true uniqueness, and being a part of it is a wonderful thing.”

Gangsta Boo and DJ Spanish Fly on Memphis’s Crystal Palace Roller Rink and Early Cunk Sounds and Dances

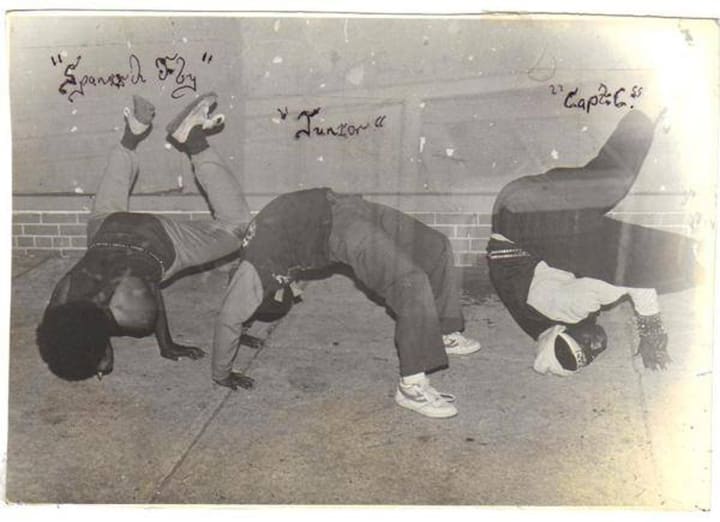

While producers in New York City in the early ’80s often sought out roller rinks to find funky, slower-paced grooves to rap on and b-boys looked to roller skating for smoothness and flow in developing early breakdance moves, further south in Memphis, Tennessee a similar alliance between rap and roller skating was being forged in the city’s famous Crystal Palace roller rink. It was there in the late ’80s and early ’90s that skate styles were gradually adapted to early manifestations of slower, booming breaks created by rink DJ Spanish Fly and legendary Memphis groups like Three 6 Mafia. As rap historian Mickey Hess describes Crystal Palace in his fascinating book Hip Hop in America: A Regional Guide, “Sunday nights at the rink were spectacle enough, with pimps, gangstas, pretty women and bad women on wheels. After the skates came off, the dances that had only begun to take shape on the skates came into full fruition on the dance floor.”

For rapper Gangsta Boo, aka Lola Mitchell, formerly the only female and youngest member of Three 6 Mafia, much of the music played in Crystal Palace defined the Memphis sound—that is, in between classic boogie and electrofunk skate jams. Here, she is joined by proto-crunk originator Spanish Fly to describe the way Crystal Palace rink culture—driven late nights by stoned, ultra-gangsta Memphis rap—spawned the crunk sound and a few of its dances.

Gangsta Boo: Me and my best friend and cousin would get dropped off literally every weekend at Crystal Palace growing up. The thing is, I could never really skate, but Crystal Palace was a real combination between skating and a straight up dance party. A lot of the jookin and gangsta walking took place at the rink—mostly with the skates off, but also with the skates on, because the slide and groove fit both, especially when Spanish Fly was playing classics like ‘Trigga Man.’ That was a huge skate song in Memphis. The connection between the skating and the dancing was the music, which was made for both.

Dance-wise, it was always a question of, ‘What can you do with your skates on? Or what can you do with your skates off?’ It went both ways. Good skaters did it all with both. Spanish Fly ran the rink musically, lots of Zapp and Roger Troutman style bounce stuff, with his own slow, booming rap in between, like “Smoking Onion.” That’s really when skaters, and later people there just to dance, would go crazy. And he played his own shit especially to shout out the different hoods in Memphis, because especially a country city wants to have their areas shouted out. And he did that with each track: White Haven, North Memphis, South Memphis, everybody. Each song called out a hood. The rink really brought different parts of Memphis together. It was a whole scene of people who met there, which formed the crunk sound.

See, Spanish Fly’s sound was slow and gangsta. OG style. With Three 6 Mafia we got into it at Crystal Palace, especially Crunchy [Black] and DJ Paul. Crunchy was always in there dancing. But sometimes the goons would come out there. There was definitely a few shootings. It fit into another song by a Memphis rapper who was there at the time: Scarface Al Kapone. His track “Lyrical Drive-By” was no joke. Memphis isn’t a flashy city, but you gotta show out, which means you had to skate to the music in a cool way. A lot of backwards skating and crisscrossing. There was a lot of coordination between skating and music at Crystal Palace.

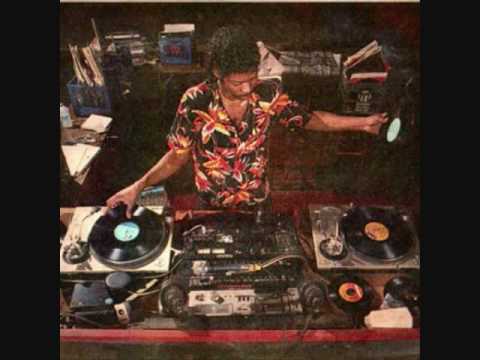

DJ Spanish Fly: I’ve been DJing for a long time, starting out when I was a kid in Clementine, which was my neighborhood in South Memphis. Crystal Palace had a very close connection to Memphis schools and my school had a special deal with the rink where every week they would take the kids to skate. Since that time I had a dream to become a DJ at Crystal Palace, so I got to know the manager really good and I ended up getting the job spinning 12-inches. A lot of this stuff was off play lists, like Egyptian Lover’s “I Need a Freak,” Vaughan Mason’s “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll” and some tracks that were a bit more up-tempo, say 120 to 125 BPM. That is, unless you wanted to slow it up.

See, different people and groups had different needs. There were tracks for faster skaters, tracks for men, tracks for women. Then, in the end, tracks for everybody. It was often split up. But as a general matter, Memphis was always about disco and then early hip-hop and electro, and the Crystal Palace owners knew I was a hot jock. So I could tell when skaters would need, say, “Set It Off” by Strafe or “Looking for the Perfect Beat” by Afrika Bambaataa. Not to brag, but I could figure out the pace of the skaters from one or two songs.

When I was going to school though, there wasn’t too much electronic stuff or gangsta stuff at the rink. It was a crowd raised on disco. In the very beginning the managers would tell us to cut more gangsta stuff off. But as a teenager I snuck into a bunch of different clubs around Memphis and that’s what really made me into who I am today, and how I became DJ Spanish Fly. At a certain point I left the rink just to DJ illegally in places like Club No Name, where I was actually too young to get in. Then, as I made a name for myself, I would get invited back into the rink for parties and special events, and that’s when they let me play my own tracks which before were way too gangsta.

This is also where my peers and then a younger crowd heard my big, slow gangsta stuff. Because they were too young to get into the clubs! My productions, the gangsta walk style music, really changed the music that people wanted to hear in Crystal Palace and how they danced. This is when a lot of people eventually started to take their skates off and dance in the middle of the floor, which is kind of a complicated thing. Let me explain: You have to keep in mind that the skate referees were the best skaters and they didn’t allow you on the floor in sneakers. That was the number one rule. But when I started playing “Trigga Man,” “Smoking Onion,” “Get Buck” and songs of that nature, they started to let people into the very inside of the rink, which was a donut hole in the middle with chairs and stuff.

But to get inside, you had to go on this ramp and avoid running into people who were cruising by fast. The rink held around 500 people, and the middle could hold around 200 people. And the middle was where you could take your skates off and get buck. That’s the real relationship to me between skating and how people danced to my gangsta stuff: gangsta walking looks like people rolling with their skates off. But back then, they didn’t call it gangsta walking. And crunk of course all came from getting buck.

Skaters loved my DJ Spanish Fly productions because they were slow and grooved. Crystal Palace was the only real place to get to hear them for younger people, and so that’s why everybody, and I mean everybody, wanted to be there. And there was a lot of parking lot pimpin’ going on, where I would sell my cassettes out of the back of my trunk, where music exchanged hands, where we’d have a little drink, where the dope boys were—all that. It was like a car show. And a lot of cats were gangsta but you didn’t know it. They were just skating, buck jumping, all that. My crowd was the robbers, the killers, the unaccepted.

A lot of people buy hip-hop today, but back in the day, the gangstas were the people who bought rap. And rap tapes were hard to find. It was like dope. When people thought roller skate music in Memphis, they thought Spanish Fly. To me, music changes everything. Music is the key. And the rink is a part of my music, like with “Trigga Man” and “Trigga Man’s Revenge.” I still think about it, “Hop in the Cadillac and roll by the skating rink.”

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2015 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. To read more from this issue, click here.

Photo of Luther Campbell by So Min Kang. Parking lot pimpin’ session images taken from the upcoming skate documentary United Skates by Dyana Winkler and Tina Brown.

Published June 19, 2015.