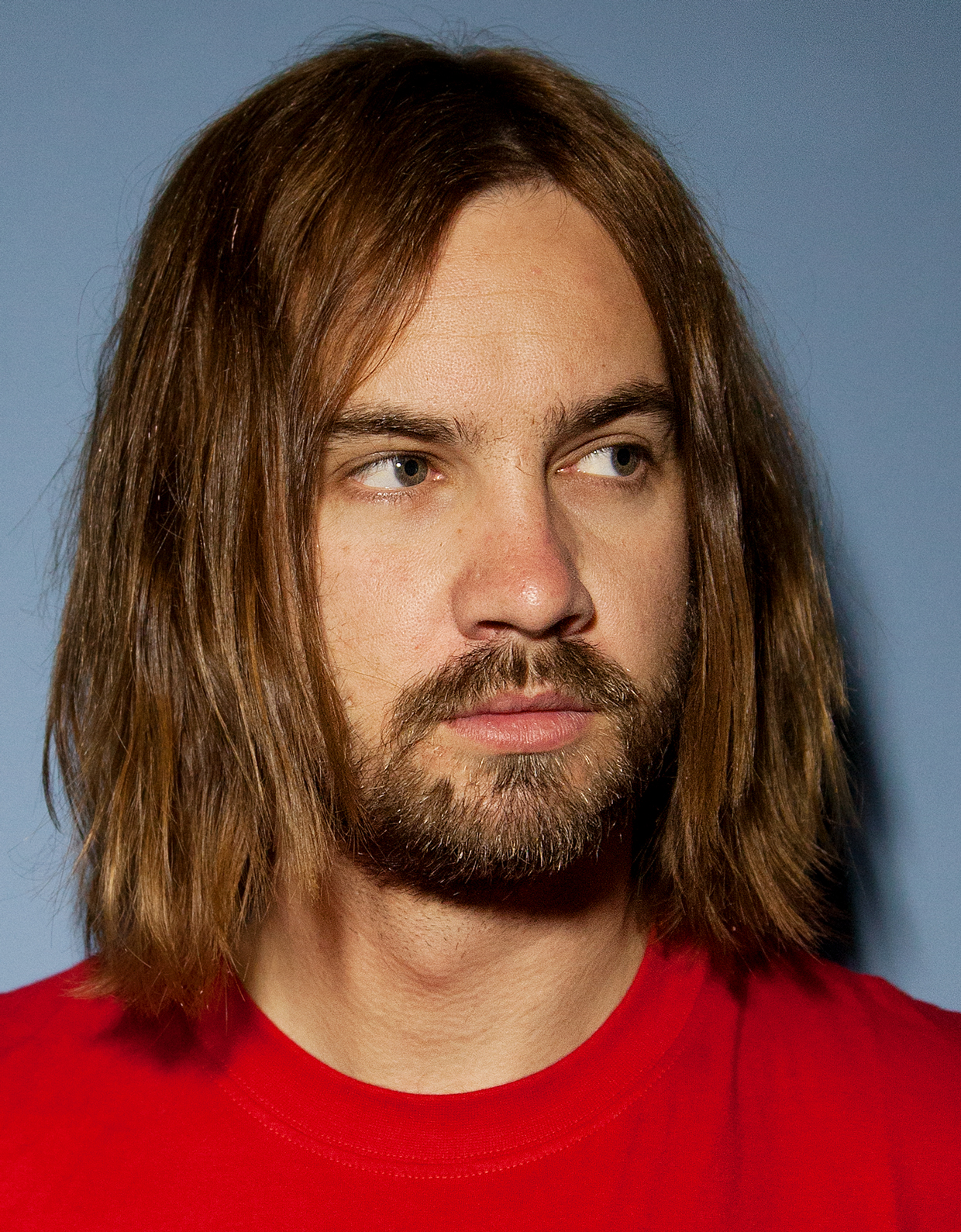

Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker Reflects on Pop Success

Hailing from Perth in Western Australia, one of the world’s most isolated cities, Tame Impala mastermind Kevin Parker might seem an unlikely candidate to top the charts alongside Ed Sheeran and Taylor Swift. But in only a few short years, Parker’s infectious brand of lysergic, riff-heavy pop has gone from bedroom project to global juggernaut, striking chords with young festivalgoers and aging psych-snobs alike. With his latest album, Currents, Parker draws on new inspiration from the funky crucible of ’80s electro-pop and a beguiling set of new life circumstances.

Kevin, you’re from Perth, which is thousands of kilometers from the next major town or city. How has that affected the music you make? Or do you think people unnecessarily romanticize the idea that isolated spaces promote innovation?

I still don’t know. There’s definitely something to be said for Perth people doing what they do to please themselves rather than anyone else. I think we have that balance going on where we’re so far away from the other cities in Australia that we feel disconnected, but we’re connected enough to know what’s going on in the outside world. We have our interpretations of styles of music that are popular in other places, so we catch on to the rest of the world. Touring in Melbourne and Sydney isn’t really in the cards for young Perth bands because it takes ages to fly there and costs a lot of money. So we said, “Fuck it, let’s not bother. Let’s stay here and make music for the rest of Perth.” Maybe it’s that sort of decision that makes the city musically productive. Since everyone has already seen everyone else play, there’s an onus to do more fucked-up shit.

Besides, I never relied on a music scene to do what I do because I make music alone, and when I started out there wasn’t a scene around me anyway. My experience of the “Perth scene” was just my friends and the people I lived with. Perth is so spread out that everyone has a huge backyard by anyone else’s standard. That was one of the things that shocked me once we left Perth: I always assumed that everyone around the world had a backyard. Only when we started traveling did I realize how naive that perspective was. We were more about backyard parties and weird jam events amongst friends that would go on for way too long.

Would you say playing outside established venues with your friends fed a healthier musical instinct? Playing in bars always seems to foster a competitive tension between young bands.

For sure. The competitive thing never changes, though. You can’t escape it because it’s human nature. I always found it constructive. Like a sibling rivalry, it only makes you strive harder. I don’t think I’d be anywhere near as good at what I do if I didn’t strive to be better than a band I saw or played with. I wanted to make music on the level of my friends. So that was competitive in the best possible way.

Do you think bands tend to get too deep into the mechanics of how they’re going to make it too early in their careers? There’s a tendency to focus on getting plucked out of your hometown by that cool, foreign label.

Before we got “plucked,” as you say, which is exactly what it felt like, I didn’t want to be a part of that grind: raise some money, record a demo, get a manager, get some more money together, record an EP, shop that around to every single person you can think of—from rural radio stations to giant labels. Then you go and raise more money from extended touring, record an album, and that’s your moment. I saw the painfully rigid structure of it.

I read that you got the call from the Australian label Modular, your pivotal “pluck” moment, on your way to a university exam. The world is pressuring you to get a life, or a “real job,” and then the complete opposite happens.

We were waiting for Modular to let us know whether they would actually go through with signing us. They’d been in contact with us before but they were like, “We need to talk to the boss,” who I guess was [Australian promoter and Modular founder] Steve Pavlovic. The call was to confirm that they would fly us to Sydney to play at a showcase for them. I was walking around uni, the exam was in 20 minutes and I was meant to be studying but I was thinking about this call. Then five minutes before the exam I thought, “Fuck, I better start walking to the exam,” and then the call came on the way there and I was like, “Fuck it, sweet! I’m out!”

After that I drove home to our share house and told Jay [Watson, touring member of Tame Impala], and we were like, “Whoa, sweet.” We didn’t even have a manager and we needed a lawyer to decipher the contract. It all went pretty smoothly after that. Each step on the ladder of success was as weird as the last. Getting flown to Sydney and put up in a lush hotel was like, “What?” Modular was so cool at that point. They put on a gig with us as the sole act in the middle of the day just because they wanted to see us. No one had even heard of us. Literally no one. And they had all these cool people there. So that was kind of crazy.

It must be weird thinking back now to something that seemed like such a huge deal at the time. Are you losing touch with the person who was stoked and surprised at something like that happening?

It’s true, which is sad. I still consider that the most exciting time of my life. The initial feeling that something great could happen is immense. Not to say that amazing things haven’t happened since then, but I’m getting better at digesting them.

I assume your resources and creative possibilities have expanded with your success. Do you feel like there’s a trade off in that regard? Are there constraints that appear in other areas to offset the appearance of freedom?

I think the more people you have involved—like with these big American labels—the more you have to fight for what you believe in. In the early days, if I thought something should be a certain way, I could say, “I think this should happen,” and I’d deal with it myself. Now it’s on a different scale. For instance, if you’re asked to stream your live set at a festival and you don’t want to, it’s a big deal. Some phone company sponsored a festival we played, and it was stipulated in the contract that the top three headline bands must be streamed, and I’m like, “No, I don’t want to be fucking streamed. I want to have a good time on stage and know that it’s not being broadcast to the entire Internet and stored forever and picked apart.” So suddenly, if you don’t want something to happen, if you want to do it your way, all hell breaks loose between managers and festival promoters and whoever. Even though there are lots of people working for you who care about your work, you’ve got to fight for what you believe in more when it becomes a bigger deal.

The business interests of the infrastructure become tightly linked with your private decisions.

That’s what it is. When more people, companies and brands depend on you to make a living, suddenly you have to please a lot more people than you did in the early days. Some people just ignore it and say, “Fuck you, I’ll do what I want,” and others are quite considerate. I guess I’m somewhere in between the two.

With Currents, you drape your signature songwriting style in electronic, funk and R&B-inspired aesthetics. The press has tended to paint this slight shift as a big, risky move for Tame Impala. What would happen if you released something that was really going to confound expectations? If slight changes in instrumentation are heralded as a fundamental change, what would happen if you released, say, a drone record?

Or the sound of a washing machine in reverse.

Not purely to be weird for the sake of it—but if your audience considers slight generic change as some huge step, perhaps that’s something to play with?

I hate the term “going electronic” or “going pop.” A lot of bands who have an established sound and a bit of success can become overly aware that people consider them to represent a particular brand of music. It’s a cool thing for them to throw those expectations out the window and make something totally obtuse. I find being inaccessible for the sake of it more of a cliché than going the other way.

Could the infrastructure veto such a move? Render it somehow impossible?

At the end of the day it’s still down to the artist. That’s probably the reason why a lot of bands make an experimental album: to pull a middle finger to the people who are expecting them to do something else. In a way that’s kind of how I felt when I was making Currents. I was making songs with a drum machine rather than a drum kit, or songs without a chugging riff. I knew that [Tame Impala’s 2012 hit single] “Elephant” did really well in America. The radio stations just kept playing and playing it months after its release. The record label was like, “Sweet, this ‘Elephant’ tune is sick.”

Ten more of those, please.

They never straight-out said that. The people we work with would never expect me to regurgitate formulas for the sake of success. But they’re probably thinking, “If he makes another ‘Elephant’, then we’re minted.” If I did, it’d get played on the radio, even if it was less inspired. As long as it was the same kind of thing, they’d be like, “Dope, there’s the next one—ship it out!”

Your production tends to get put on a pedestal, and people like to emphasize your self-questioning isolation within this dreamy soundworld. Album titles like Lonerism and Innerspeaker make such a connection quite immediate. While Currents is aesthetically pleasing on the surface, there’s an insidious aggression in it that’s contrary to the production style.

Some people focus purely on what the sounds say to them. The production style forms their opinion of how optimistic or pessimistic an album is. For me, Currents is meant to be about looking forward and a sudden adoption of confidence. Suddenly this interior voice is declaring what they are and what they want, as opposed to the other albums, which are more self-questioning. The overall consensus on Currents was that it’s heartbreaking and really sad, which kind of confuses me because Lonerism was really dreary in comparison. The lyrics are quite defeated, and Lonerism in general has a depressed tone to it, yet people were saying it’s really upbeat and positive. It’s weird that I always seem to have the opposite interpretation of my music.

Production can be such a red herring that it can say one thing with this hand and another with that.

Oh man, that’s one of my favorite things about music: putting two different kinds of sentiments together. I always thought a sad song with sad music and sad lyrics is one-dimensional. When you juxtapose positive lyrics with a melancholic sound, suddenly you have this weird friction that plays with your emotions. That’s one of my favorite things to do. I gravitate towards that musically.

Would you consider production to be surface or content? Some critics say your production keeps listeners away from meaningful interaction with the actual content of a song. Do you consider production musical material in and of itself?

My instinct is to say that it’s extremely inherent in the music. Production is the music as much as the aesthetic dressing because so much of how a sound comes across dictates how the brain responds to that sound. If you play a guitar nice and clean with some country rock strumming, it says one thing; if you overdrive it, suddenly it’s a really angry, aggressive chord with a completely different emotional value. And that’s what production is: it’s how the sound gets from the source to the ear. So from the ground up it has emotional weight. I dream about being a hotshot producer in the same way a kid dreams of being a rock star. See, for me, production is part of the songwriting process. I’m completely unable to write a song without considering how it would be produced at the same time.

Surely there are loads of people asking for your services.

You’d be surprised. I think there are a lot of production requests coming from fans sent to my manager. She filters through them, so not many requests actually come to me. Some big names have asked me to produce their stuff. I wouldn’t be able to say who, because then I’d be saying whom I denied. Sometimes I say no because I love their music and I’m too afraid to fuck it up and ruin it for them. It’s such a personal thing; people have to know each other to work together properly.

Now that you’re playing these huge festivals, is there any sort of musical monotony setting in or does the mega-festival keep surprising you musically?

I’ve slowly become that guy who doesn’t check out bands, which seems to be the ultimate sign of becoming a jaded festival veteran. You just rock up, play your gig and piss off. I still maintain that you can learn something from every artist you see, especially watching them on stage. That is, if they’re not exclusively using backing tracks. Having said that, I don’t go out looking for my new sound. I wait for it to come to me. Music has always come from such an internal place for me. I have a hard time thinking about it any other way.

When you’re a teenager, music can be a huge factor in shaping your identity, maybe because it comes from a highly personal internal place, as you say. I guess that especially goes for musicians. But for most, real success will remain a fantasy and their identity readjusts to everyday life. But when the opposite happens, I imagine music can have a volatile influence on your sense of self.

Absolutely. I guess that’s why artists go crazy. [Long pause] That’s how insanity happens.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine with photos by Luci Lux. Click here to read more from past issues.

Published January 04, 2016.