Amid Censorship, Tehrani Dance Music Emerges From the Shadows

"These limits never stopped us from what we are doing": Key figures in the Iranian scene reflect on the struggle to make their voices heard.

Tehran is a city where you can get thrown in jail for listening to Pharrell Williams yet have all manner of drugs delivered to your doorstep in less than 30 minutes. This is only one of the many paradoxes that exist in the Islamic Republic of Iran, a country most governments officially warn against visiting. Despite these facts, however, Tehran is slowly making a name for itself in the electronic underground and redefining its image through the medium of sound.

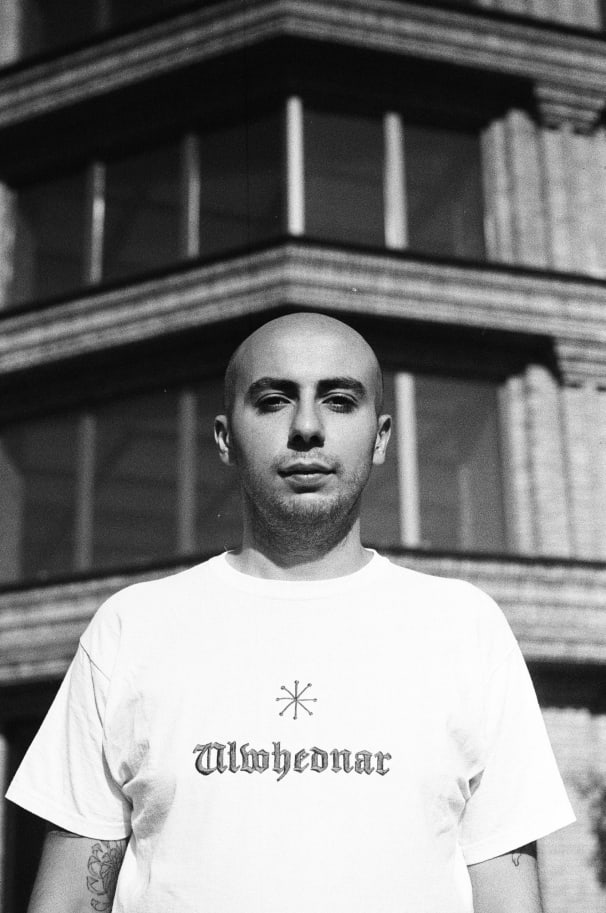

“There are a lot of problems in Iran, but I also feel lucky to be born here because it gives me an opportunity to be a pioneer,” says Azim Fathi, the founder of local record label and party series Paraffin Tehran. “I understand what it means for everyone else, not just for Iranians who respect this culture, [but for those who] share a love for freedom of expression.”

In the wake of the 1979 Islamic revolution, the Iranian government turned pop music into forbidden fruit, condemning it as indecent and a threat to their Islamic messaging. For some time now, Tehran’s underground has existed in the shadows through clandestine house parties in the city’s outskirts, where drug-fuelled raves can operate free from the interference of the bolshie religious police. While the house party scene continues to thrive and tend to the urges of Iran’s rave enthusiasts, new public events are bringing the sound of the underground to different audiences. In the long term, this could have a lasting impact on how the Iranian regime views electronic music.

This groundbreaking sea-change—the allowance of live DJing in Tehran—started some five years ago, Azim tells me. It’s likely no coincidence that it happened in tandem with Iran’s negotiations with the US and Europe to remove restrictive economic sanctions. During this period, Iran was beginning to open up again, tourism rates were rising and young Iranian progressives were full of hope that the country would soon be embraced by the rest of the world. When the US reinstated sanctions in 2018, it sent Iran’s currency into freefall and locked the country off once again, into a state, in some ways, even worse than before. Iran today is very different from five years ago, but electronic music events have weathered the storm. DJs continue to play out in intimate venues across the city, from cafes to galleries, during the day.

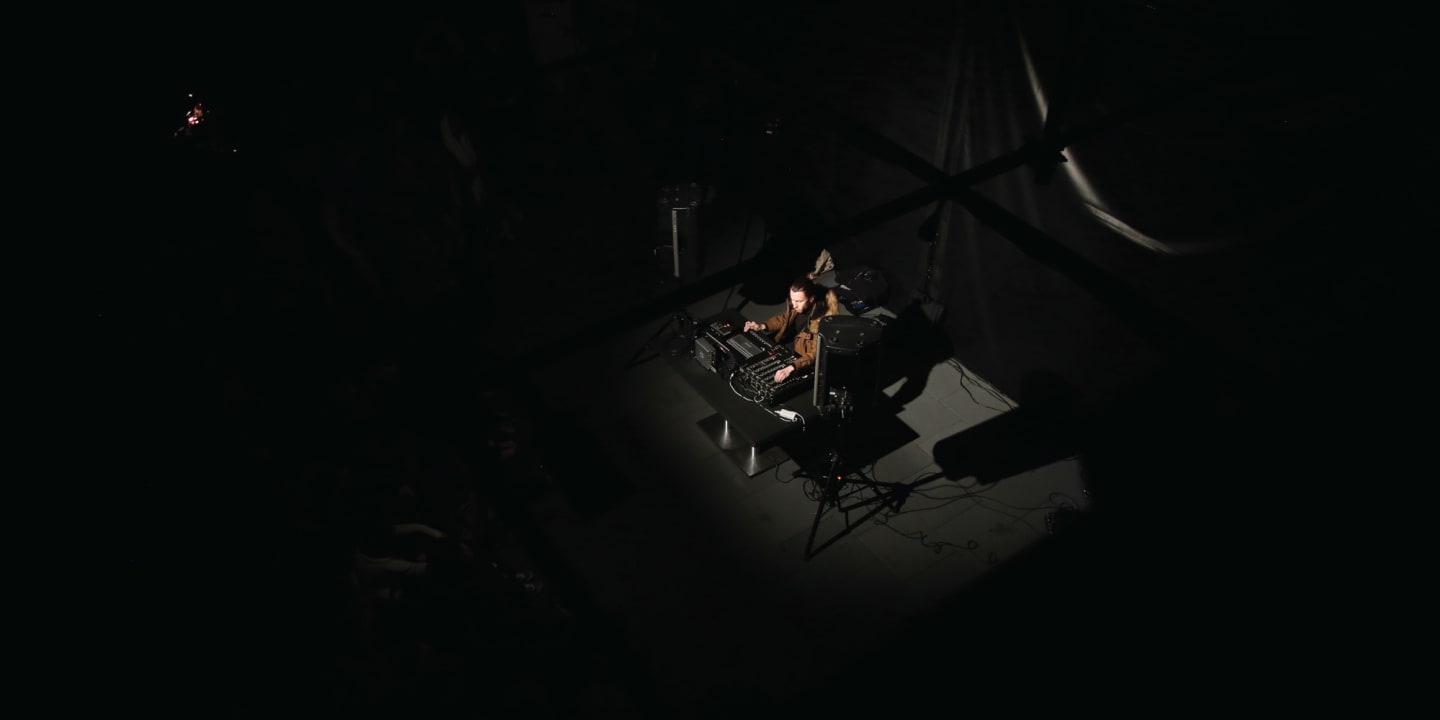

For those behind Tehran’s growing scene, like Azim, it’s more of a labour of love than an economic pursuit. Azim’s dance music collective, Paraffin, organizes around six to ten events a year, but putting on an event is far from easy and close to impossible to profit from. In order for the government to give a show the go-ahead, performers and promoters need to send in music that will be played so authorities can listen to and approve it. The first time Azim applied to put on a show, the authorities also asked for a video recording showing how DJs will perform onstage to watch for their facial expressions and reactions.

“That’s how closed they are,” Azim tells me. “They say ‘reserve two seats for our guys,’ but normally they don’t have time to check every performance and they don’t really care in reality.” Still, performers and promoters have to decide whether to risk straying from the submitted event proposal.

By loading the content from Soundcloud, you agree to Soundcloud’s privacy policy.

Learn more

Curiously, these musical regulations have impacted the type of sound coming out of Tehran. If the authorities cannot categorize the music, they allow it to be played. “A lot of music that’s happening here in Iran is really muddy and abstract,” Arash Molla, or ArtSaves, says. “That’s why I think we have a good ambient and experimental music scene here above anything else, partly because we were never allowed to play a specific genre, so people moved to more abstract music that you cannot define—to be able to play it here.”

Inspired by Tehran’s changing sound and his own desire to move away from loop-based and western-centric approaches, Arash’s latest EP, Bore, is darker and more distorted in sound. “Apart from our political [views], we don’t tend to express ourselves clearly. To the point that it’s kinda our aesthetic to be ambiguous,” Arash says. “This [experimental sound] goes back to our childhood because we have never been able to express ourselves clearly. And that’s why even the [melodies are] under a lot of reverb.”

The growth of Iran’s electronic scene is especially impressive considering Iran’s economic backdrop, which has had a knock-on effect on local DJs and producers. Iranian fans can’t buy music from musicians because they don’t have credit cards. CDs and vinyl can’t be posted to Iran because the US sanctions effectively forbid international companies from transacting with the country—the same goes for production or mixing equipment.

“I believe everything surrounding us affects the sounds we make, unconsciously, but these limits never stopped us from what we are doing,” Behrang, part of the Tehran-grown electronic duo, Temp-Illusion, explains. “To be honest we became hopeless from time to time, but at the end we found ourselves doing it again and again.”

Temp-Illusion’s atmospheric and experimental soundscapes have seen them become an integral part of the Tehran underground, and they’ve performed at Paraffin events and elsewhere in the city. Though Behrang and Shahin both have separate solo projects for other purposes, their work with Temp-Illusion draws inspiration from their surroundings in Tehran and all of the variables that come with them. “It’s undeniable that there are some limitations, but these limitations couldn’t affect our sound except [through making us] more eager about learning and producing,” Shahin from Temp-Illusion added. “I think we’re somehow representing how this city sounds in our view.”

A lot of these supposed limitations have led to the adoption of a kind of communist-style approach in the underground, echoing some of the defining aspects of Persian culture, like giving generously to friends and strangers alike. Since downloading music or ordering vinyl is impossible without a credit card, Iranians have resorted to sharing their music with others for free or uploading tracks for streaming purposes only.

Iranian underground parties also follow a similar structure: since charging people to enter would create more hassle if the police discovered the party, no one pays anything. But the parties are exclusive, and you need to be known and trusted to be invited. The risk of being caught and punished is ever-present, but it’s a risk Iranians have been willing to take for the sake of music, partying and cathartic release.

After being caught and thrown in jail for ten days alongside his friends, however, Azim now tries to be more careful.“That shit was like a movie in itself: how we all managed to get out of that shithole we were in, and how high we all went [to jail] when they captured us…it was a nightmare,” he laughs through the phone.

Though risky, these clandestine parties are necessary. Tehran’s scene is limited in the public sphere: officially, observers can’t dance, and DJs often need to modify their sets to minimize problems with the authorities in case they do decide to turn up. Nonetheless, people like Azim are clearly playing a long game, and that’s partly because of their love for the city. Azim has to manage the restrictions and make it work within the framework that exists, and slow and steady progress and changing attitudes towards electronic music could have big pay-offs further down the line.

Arash says that having more international exposure will help Iranian artists and the local scene, and DJs and producers can bring back what they learned to their home turf. Because of the effort required to throw events, even the biggest producers in Tehran normally only play twice or three times a year in public, and playing abroad also springs difficulties, since artists need visas to play.

“People take advantage of any little opportunity to play [in Tehran]—at cafes, at house parties. We are doing it, but a chance to play outside will give the artists a better view of what’s happening in music,” Arash says. “It would give us the opportunity to grow and see how things are getting done outside of Iran, seeing other peoples’ workflows and collaborating.”

Because of the sanctions and currency devaluation, booking international DJs is now some 12 times more expensive than it was before 2018. But that hasn’t stopped Paraffin from booking some of the best acts from its neighbours in the region, like Bassiani’s HVL. “So many artists give us a [booking fee] discount because they know the situation and that it’s impossible to make money. So they are basically investing in the culture of the city,” Azim explains.

Now, with the vicious outbreak of COVID-19 that has devastated Iran, the country is battling challenges that are putting a stop to music events and hampering the economy even further. Iran is one of the worst-hit countries in the world. “We were invited to go to a private party a few days ago. But in the end, the guys decided to cancel it because it was not really a wise decision, even though we are all healthy,” Azim says. Tehranis have to stay home at the moment, and that’s given artists like Azim the chance to focus on the Paraffin podcast series, create podcasts for other collectives, and focus on finishing music projects that he’d already started.

The onset of COVID-19 has effectively quarantined all musicians and brought nightlife to a standstill. Nonetheless, with the increased use of streaming platforms and more time available to spend listening to new music, it’s easier than ever for the international community to discover Iranian musicians and find ways to unite in uncertain times. “Through live streams, radio shows, guest mixes, interviews and all the other online tools, there are still ways to collaborate,” Arash says. “So by putting in a little effort, [the international community] can find worthy Iranian artists to cover, hopefully based on high standards regardless of their nationality and the current political situation in Iran.”

Miriam Malek is a freelance journalist with a focus on counterculture and Middle Eastern politics. Follow her on Twitter.

Published April 23, 2020. Words by Miriam Malek.