The article you’re reading comes from our archive. Please keep in mind that it might not fully reflect current views or trends.

“Testing things to destruction is probably the best way to test things” – Max Dax talks to Squarepusher

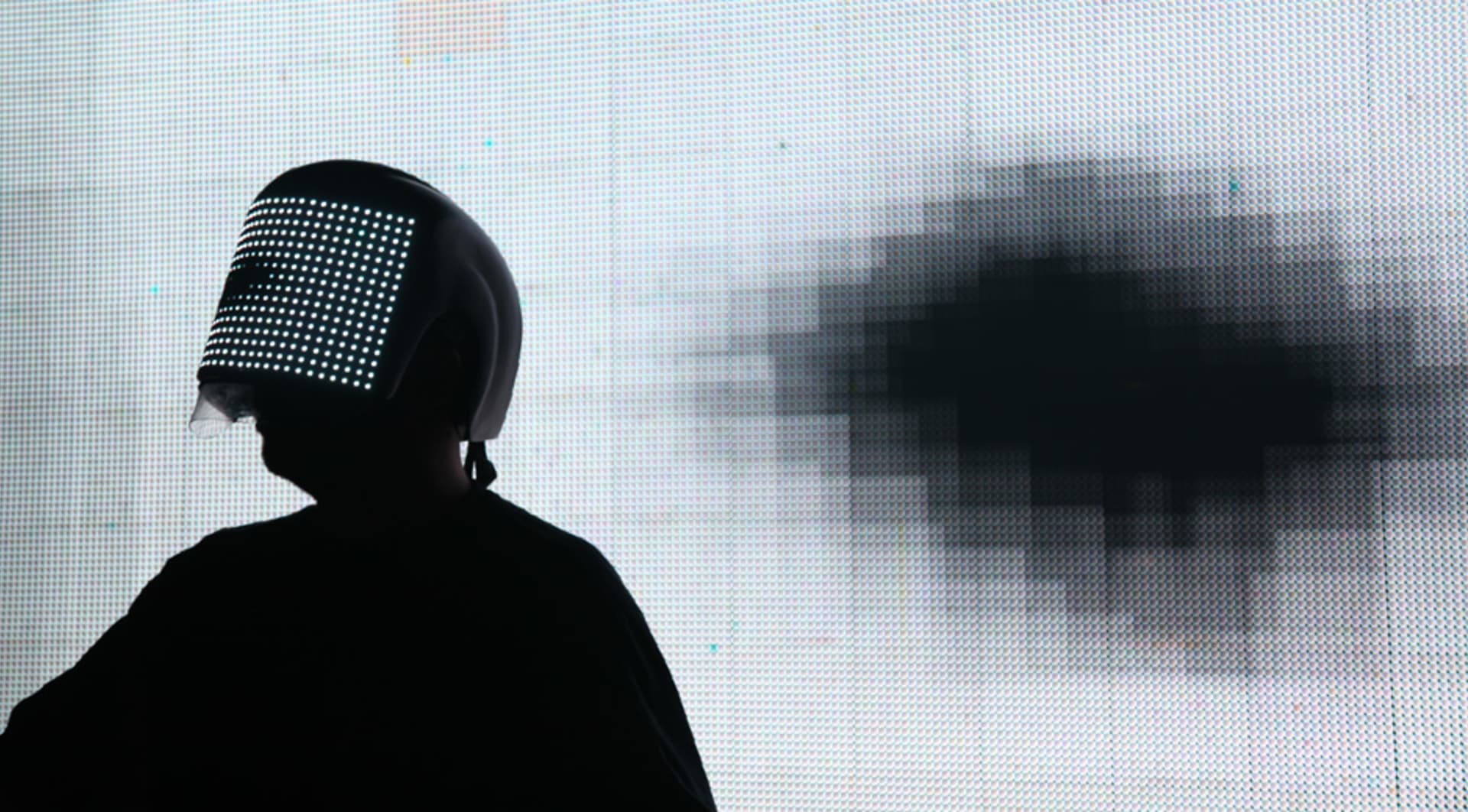

In this in-depth interview from last summer’s issue of Electronic Beats Magazine, Editor-in-Chief Max Dax speaks to electronic music’s great British eccentric Squarepusher. Here he talks about growing up his early obsession with radio bands, musique concrète and why having “entertainer” stamped on his visa doesn’t quite cover it. Main photo from EB Festival 2012 in Gdańsk by Luci Lux.

Tom Jenkinson, aka Squarepusher, was born in 1975 in British synth-rock Mecca Essex, homecounty of myriad classic electronic acts, including Depeche Mode, The Prodigy and Nitzer Ebb. But despite the local lineage, Jenkinson grew up knowing little about band histories and pop cultural contexts; he was too busy building his own radios and obsessing over circuitry. The unabashed electronics geek had a special interest in radio in its entirety: the noise, the interference, the music (all of it), and the ability to jump from broadcast to broadcast by spinning the dial. Today, Jenkinson has come to see radio as “the first instrument I learned to play,” and the beginning of an interest in both content and method—electronic music and how it’s made. It’s an appropriate history for an artist widely considered to be one of the most innovative acts on Warp Records’ roster of digital envelope pushers. On Ufabulum, Jenkinson once again applies his special brand of programming ingenuity and musical ability to create even bigger, more pulsing breaks and futuristic rave anthems, not to mention a live show equally as seizure inducing. In a good way.

Tom Jenkinson, you’ve created an impressive LED set-up to visually represent your music. How complex was it to realize?

We’re forced to use different gear every night, so there is quite a bit of trouble-shooting every time we build the huge LED screen up onstage. We always have to rent a good chunk of the equipment locally because it would be too expensive to travel by plane with. That’s probably the most complex aspect of the whole experience—to deal with new, unexpected problems on a daily basis.

Did you design everything yourself?

Well, I programmed everything that you see. That’s all my work.

It’s interesting how much effort you’ve put into staging your show. Instead of hiring somebody to take care of visuals, you seem to spend an equal amount of time and energy on it as on the music.

Absolutely. I guess I must have learned it from Kraftwerk. They do everything themselves, and they let no outsider into their creative inner circle. I hate it when something gets lost in translation, and in my case, I’d literally have to explain a picture with words that someone else would have to paint. It’s obvious that the result would be different than the picture I want. As it currently stands, what you see is like a negative or an inverse visual inspiration of my music. I definitively didn’t want to do something like all the others—to use found footage from TV to illustrate my tracks. I hate random or arbitrary visuals because they tend to draw attention away from the music. If what I’m displaying on stage doesn’t lock-in with and accentuate the sonic experience, then I don’t see the point.

Are the visuals triggered by acoustic signals?

Partially. There are two sources of control data: The first is the audio, with each separate signal broken into different instrumental sources. Those sources then get analyzed for pitch, amplitude, waveform irregularity, which in turn function as visual control parameters.

So when you improvise, the visuals will be different?

To an extent. If I affect the audio then obviously the visual parameter it controls will also change.

What about the second source of control?

That’s pure code—instructions that tell the screen to strobe at a particular frequency or change the dimensions of an object being displayed.

That’s a very technical description, but you could also say that with your stage set-up you’re operating a kind of childhood fantasy. You look like you’ve stepped right out of a yet-to-be-made sci-fi flick with your futuristic helmet and the thick data cable that connects it with your machine. It’s like Matrix come true.

I’d probably say that I’m in a state of arrested development. Of course, I mean that half-seriously because I think children love exploring and learning and playing with things without having any specific objectives in mind. It gets harder and harder to do that as an adult.

Doing things without objectives?

Exactly. And that’s why an integral part of my work involves reserving time to carry on with that kind of playful exploration.

One way to maintain that spirit as an adult is to force yourself to do things on a daily basis that you’ve never done before.

That’s a good way to keep yourself open minded. Of course, you can’t always live like that. Every now and then I need to get an analytical overview and think about where things are actually heading—that is, when I’m not doing pure research. I guess I split my time between child-like experimentation and figuring out adult-like objectives.

You once said in an interview that as a child you were fascinated by the size and sounds of power stations and big machines like Ferris wheels.

I’ve used noises from both in my music.

Would you say your music is like a coded language and you’re the only one who’s able to decipher the origin and history of a particular sound? Is there meaning in the original sound sources?

I’m probably not the right person to analyze what I am doing.

But you could describe it.

Well, the Ferris wheel sounds exist for real. The power station I think of more abstractly. You see, from a very young age I was fascinated by electricity, so I constantly read books about it as a kid. One of the books I had was about how power stations worked, and there was a time in my life when I almost lived inside this particular book. I memorized all the pictures and the descriptions of how it worked—how steam rotates the turbines and how the generators produce the electricity that’s being fed into the substations and then into the electric grid. I have this fascination with networks, and the way electricity is distributed is probably one of the best examples of how a network can function. As a kid I was also captivated by circuits. I often thought about electricity going through the pathways, being split here and there and changed into different quantities by various components… and then switched into new pathways.

Radio waves are also at the intersection of music and electricity.

Yeah, and that’s another one of my obsessions. But I’ve always been interested in both the technique and content of broadcasting—how and what music is projected through space. One of the most basic things to do as a kid when you’re into electronics is to build your own radio. Building a tuned circuit which could decode radio signals and then transmit them to loud speakers so that I could hear them: that was magic. The moment when I could listen to music on my own radio for the first time enthralled me. I never really lost that feeling of wonderment about the discovery of electricity and radio waves. I don’t like thinking that it just exists; I tend to see it as a huge man-made effort in scientific advancement.

Discovered by Madame Curie… No, Hertz?

Yes, via James Clerk Maxwell. I was always intrigued by tuning the radio, as well as switching it on and off. I suppose the radio was the first musical instrument I played. I used to just go through the bands and listen, less to specific songs and more to the range—that is, where I was being connected to. Especially with shortwave, where you can find stations in Siberia and Asia and all over the world, with all the foreign languages and distorted sounds. That I could flip in no time from a song being played in Gibraltar to another in Moscow strongly influenced my listening habits.

You mention distorted sounds—those also seem to play an important role in your music.

Like I said, I like the artifacts of the broadcasting; the things that are present but not intended. I like noise, chopped up pieces of music, distorted voices speaking in foreign languages. I see it all as one. I see the programs and the noises in between as a single listening experience.

It sounds like musique concrète.

Absolutely. The radio is like a junior musique concrète development device, like the tape machine. It was an equally defining moment for me when I realized that I could record and play back my own voice on cassette—as well as the sounds from the cars on the street, ambulances, and my mother’s washing machine. I soon realized that I could easily build up a sound archive with my cassettes—the only limitation being the amount I owned. And again, it wasn’t all about the content. It was also about the cassette itself and the sounds you’d get when you played around with the play, the fast-forward and the record buttons. There is no easier way to get pitch modulations than fucking with your cassette player. I’ve ruined many with that kind of abuse. But as a kid one rule always applied: testing things to destruction is probably the best way to test things.

Einstürzende Neubauten’s Andrew Unruh has similar stories about his unconventional uses of contact microphones, like attaching them to subway ticket machines. Of course, the result was usually incorporated into a song.

I never met him, but I know his work of course. We seem to be like-minded. And in that respect I don’t see myself that much as a musician. I rather see myself…

Yes?

A strange thought occurred to me right now. Every time I apply for a visa and work permit in America I have to describe how I’m earning money. Then it’s up to the border authorities to classify me. When I finally get my visa, it often says: “Tom Jenkinson, Entertainer” or “Tom Jenkinson, Composer”. It makes me laugh when I read it, because it seems like such a horribly limiting description of what I do; I am as interested in the ways of doing things as the things themselves. As a musician, I have always used conventional instruments as much as I have field recordings or electronics or computers. I really don’t care about sound sources or methods as long as it fits to the big picture. Everything for me has musical potential.

Did you listen to a lot of musique concrète—Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry, Eliane Radigue?

Yes, but not as a child, obviously. As I said before the radio was my first contact with music. But I was never really interested in who was playing the music that I heard. For me it was always this box, not a particular artist or group or composer. It was about the airwaves. Radio was depersonalized. There was no artistic hierarchy. I never differentiated between quality and bad commercial music. But, of course, I became aware of these classifications later on through other people.

You were never a fan of specific genres or musicians?

Not as a child. In fact, biographical details of the artists bored me to death. I wasn’t curious. Instead, I thought about being an artist myself. I wanted to know how it was done.

While listening to your new album, Ufabulum, I keep hearing what sounds like church organs beneath all the breakbeats and rhythmic complexity. Just before this interview I was listening to it with the bells of a local church here in Gdansk in the background—it seemed to fit perfectly.

The primary school I went to was affiliated with the local cathedral, so we’d be marched up there on occasion. I’d like to stress that I am not a Christian, but I did go on a weekly basis to take part in church things. I’ve forgotten everything about the services, except the organ. It absolutely annihilated all of the other impressions I might have had. It was the only thing I was interested in in the whole building. And it fascinates me to this day. If you’d ask me who’s my favorite composer, I’d probably say Olivier Messiaen—Complete Organ Works.

I DJed once before a Keiji Haino performance at the Berghain. I played a couple of Messiaen’s organ compositions over the Funktion-One system and it was just mind-blowing… for me as well as for the audience.

I have so much admiration for Messiaen, but what I also find striking is that the potential of composing for organ has yet to be exhausted. I’ve worked on a church organ myself and I will say right now: this is not a purely historical machine. It seems utterly conceivable somebody making contemporary music could do it exclusively with a church organ.

You called it a machine…

It is a machine.

One of the oldest machines that exist. I like imagining how it must have been for people living in the fourteenth century; listening to a massive cathedral organ must have been an otherworldly, futuristic experience.

You know, Messiaen’s compositions for organ were composed in the 1940s but could have been written or played hundreds of years ago—technically speaking. I mean, what he did was historically determined, and it wouldn’t have been possible without, say, Bach and what came before him. But in a purely technical sense, the parameters given by the machine were the same at the time when he composed his organ works as they were in the fourteenth century. I sometimes ask myself how these instruments will be played in two hundred years. How will people write organ music in the future? I like to think about breaking conventions, social and logical. I imagine the music I make today like a Messiaen organ compositions four hundred years before it happened.

A vision of the future from an alternate reality?

With my music I try to steal from the future. I know about the difficulty inherent in claims like that, but sometimes I feel constrained by history. One of the most important things for me is to avoid any redundancy in my music—not only in historical terms, but also within my own work. So if I do something, I have to honestly be able to say it contains something new. Otherwise, I don’t see the point. ~