The Brazilian State vs. Baile Funk: The Blame Game of the Pandemic

Faced with police brutality, rising infection rates, and a negligent government, the favelas of Rio de Janeiro have had to turn inwards for support.

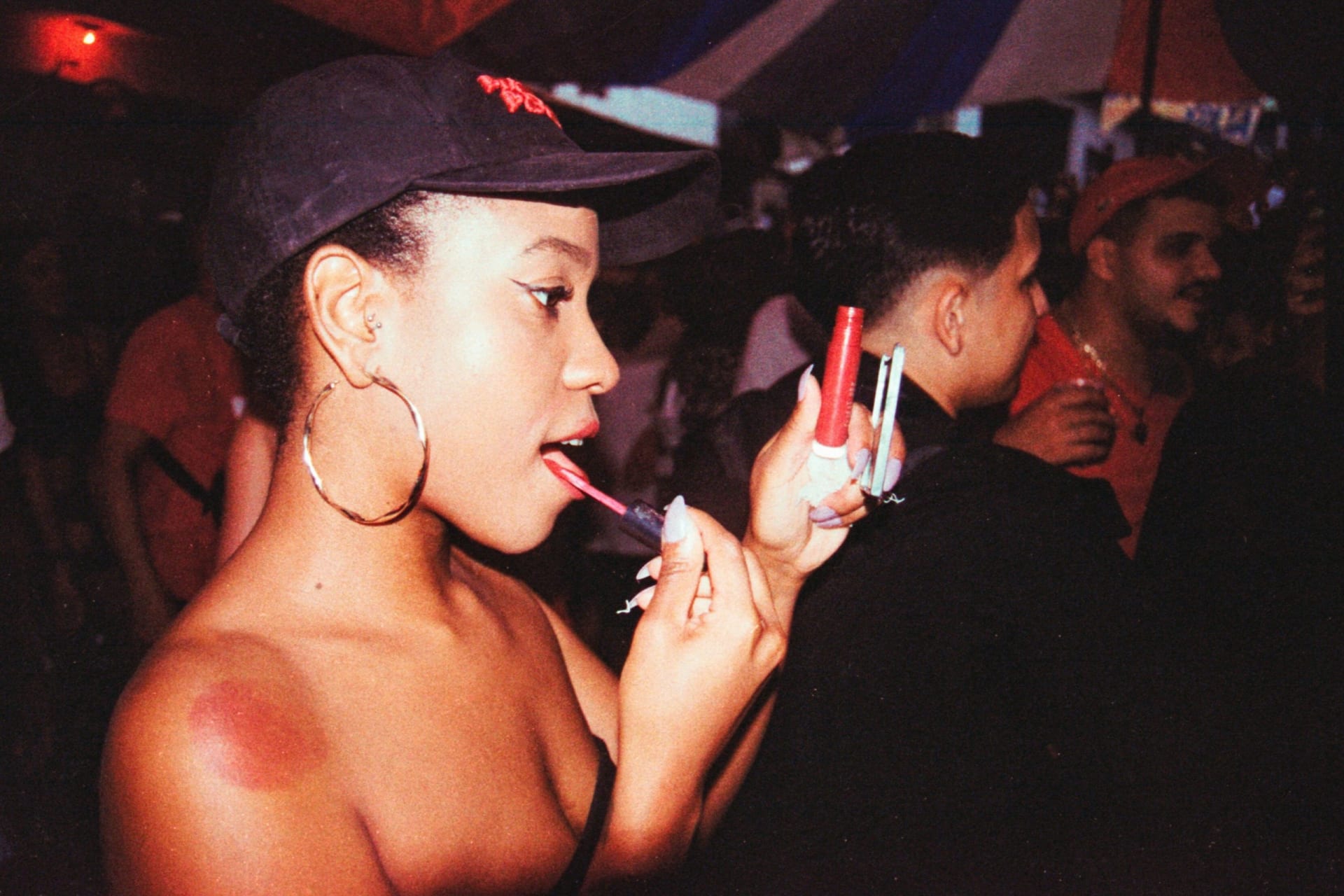

In early March, during one of the last editions of the Santo Amaro Baile, located in the southeastern end of Rio de Janeiro, an enthusiastic crowd jumped up and down to DJ Leo Big Mix’s set. The floor beneath the piled sound system trembled as about 300 partygoers shook their hips with fury in time to the rhythm. Almost every face glistened with sweat. The high energy of the revellers, dancing to beats over 160BPM, was one of the last moments of euphoria that Leo and the rest of Santo Amaro would experience before becoming the hostages of an invisible threat.

Leo Big Mix is a DJ and organizer behind Santo Amaro Baile, where he frequently plays. He is of average stature, has strong eyebrows, deep brown eyes, and sports a trademark goatee. Naturally optimistic, he has a tendency to always search for the silver lining— even in the worst situations. “We’re already trying to find an alternative to what we can do [to make an income]. The folks from the baile funk scene still couldn’t find it. We were all caught by surprise, but we will soon find one,” he said a few days after the virus became a nationwide threat. But the situation got worse.

Even with a majority of Brazil’s population quarantining at home, the mortality rate during police operations skyrocketed, and not by chance: The victims were predominantly Black and living in slums. In one crucial case, roughly 3 months ago, 14 year old João Pedro was playing with his cousins during an operation in the Salgueiro Complex, a slum in São Gonçalo, which is a city located about 22km southwest of Rio de Janeiro, when he was fatally hit by one of the many shots the police deliberately fired at him. 72 bullet holes were found in his home after the incident. This was no isolated case: João Pedro is only one of the many victims of police violence. 23,000 Black men are murdered every year in Brazil.

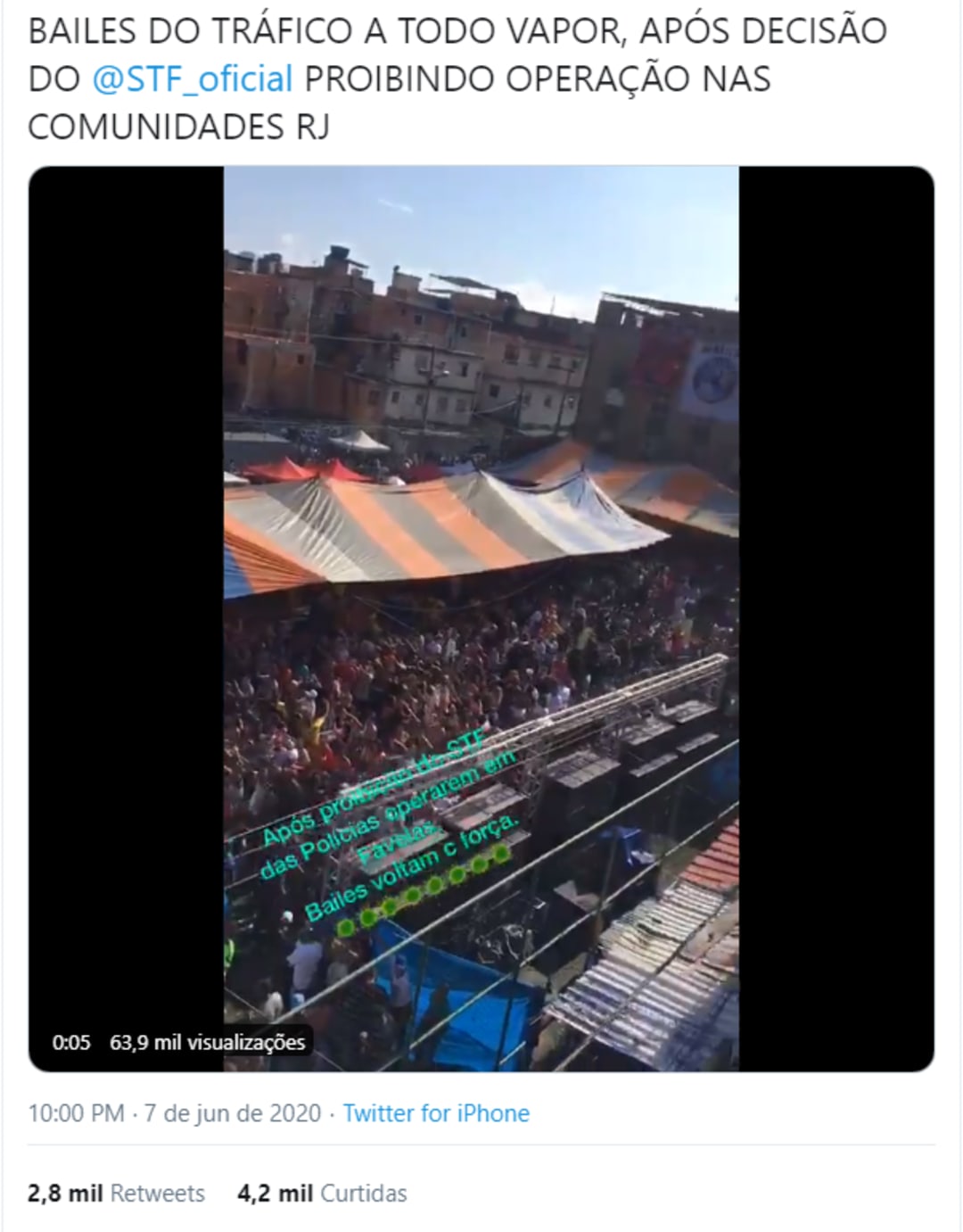

The Supreme Court Minister Edson Fachin mentioned João Pedro on July 5th when he announced his decision to suspend all police presence in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro during the pandemic. Only two days after this decision, however, an unknown source posted a now-deleted video of a baile swarming with people on Twitter, with a caption tagging the Supreme Court declaring, “Drug mobsters’ bailes going full steam after the Supreme Court decision prohibiting operations in the communities of RJ [Rio de Janeiro]”.

The video showed a baile hosted by MC Poze at Nova Holanda, a favela from the northern neighborhood of Complexo da Maré in Rio, as if the favela residents were intentionally shirking state mandates, but the footage had been taken months prior. The actual event occurred on March 11th, three months before the Supreme Court imposed any restriction on public gatherings. But these inconsistent facts didn’t stop the video from being retweeted almost 3,000 times and making its viral rounds across countless group chats on WhatsApp—a platform already known to serve as a source of political misinformation from the far right in Brazil.

Since the novel coronavirus hit Brazil, the country’s mainstream media outlets have attempted to frame the bailes as a mass source of infection, meanwhile ignoring large-scale gatherings that have taken place in wealthier neighborhoods. The favelas, and specifically the baile funk scene, are not only being blamed for the spread of the virus, they’re also being targeted in violent actions that would otherwise be more visible to public scrutiny. The pandemic only catalyzed the already tumultuous political climate in Brazil.

The Supreme Court’s decree didn’t stop the operations in Rio; they just became more brutal. Complexo da Maré, where the bailes of Vila do João and Nova Holanda take place, remains a police target. Inside sources from the location claim that now, instead of firing guns, law enforcement began executing people using knives, so forensic examinations were unable to frame the perpetrators with ballistic evidence.” Last Friday [July 31st], they invaded two communities in Niterói,” says Leo Big Mix, “Their actions are truculent and thoughtless. The police have no goal. They tell you that they just want to make the event stop, but it’s not their true intent. Their intent is to hit, humiliate, and treat the attendants of the baile like criminals. It’s revolting.”

Since the authorities are persecuting vulnerable areas during a time when they should be providing protection, communities have had to turn inwards for aid. Several initiatives that offer on-the-ground support have since emerged from local collectives, neighborhood associations, and concerned citizens. Frente CDD is one of the latter. Based in the Cidade de Deus favela in Rio de Janeiro, the project was founded by a group of residents who have taken on the responsibility of gathering and distributing donations, water, and hygiene kits to the community. Deize Tigrona, one of the community’s baile funk legends and first women to pioneer the genre, has been a vocal supporter of Frente CDD across her social media platforms. Leo Big Mix himself has also contributed to aid efforts through Juntos Pelo Santo Amaro (“Together for Santo Amaro”), an initiative which functions similarly to Frente CDD but existed prior to the pandemic. He claims that the majority of contributors belong to the community, even though its locals are living under very precarious conditions themselves.

Leo also took part in the fundraising project Funk Solidário (“Solidary Funk”)—a series of live streams on Instagram featuring Sany Pitbull and DJ Cabide, two MCs who have had a crucial role in baile funk’s history, that distributes groceries to baile funk workers in need. They donate to MCs, technicians, car drivers, as well as others in the scene. In an Instagram post, they highlighted the importance of these relief funds, saying “We are the first ones to stop working and the last ones to get back on track.”

Many favelas have set an example in Brazil by acting swiftly to prevent the spread of the pandemic. Rocinha, the biggest favela in Brazil with a population over 100,000, banned tourists from entering the area. On March 13th, the president of Rocinha’s Residents’ Association, Wallace Pereira da Silva, requested the state tourism secretariat, to enforce travel bans on foreign visitors. Up until the coronavirus hit Brazil, it was not uncommon to see safari jeeps loaded with tourists in places like Rocinha or Vidigal. Travel agencies often offer package tours with visits to favelas (some are specialized in favela touring), creating a culture of voyeurism where tourists are encouraged to gawk at the neighborhood inhabitants in the same way they might survey animals at a zoo. Many of the clientele include western Europeans, and Wallace Pereira da Silva’s appeal to the secretariat reflected his concerns over the state of Italy and Spain, which had over 20,000 cases at the time.

Vacationers travelling home from Europe were the ones who initially brought the virus to Brazil, but the devastation quickly shifted to impoverished favelas and prisons. Rocinha borders some of the country’s most affluent districts, but its dwellers don’t enjoy the same access to clean water and health care as their wealthy neighbors.

By early May, Brazil had become the center of the pandemic. President Bolsonaro, who had openly dismissed the effects of the virus and mocked the impact of the pandemic, tested positive for COVID-19 on May 13th, shortly after he dined with President Donald Trump in Florida. Later in the same day, he shared negative results and then denied ever testing positive. Bolsonaro tested positive once more on July 7th, but his history of fake news scandals dating back to pre-election led people to question his inconsistencies across social media.

Many skeptics linked the recent positive test result to Bolsonaro’s involvement with the lobbyists of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. The substance was proven in a laboratory study that it could be used to stop COVID-19 from entering cells in vitro; however, later research showed that it didn’t work with cells in the human body. Between March and April, against the former health minister’s advice and without technical endorsement, Bolsonaro ordered the army’s lab to produce chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine at 84 times its former domestic output quantity. The lab is now under investigation by the Federal Audit Court for overbilling a medication that has now been proven ineffective against COVID-19 by the World Health Organization. The drug is not only useless, but it also causes severe side effects that are, in some cases, fatal. Since the start of the pandemic, the consumption of chloroquine has risen 358%, much to the benefit of its three main manufacturers, whose owners are all early Bolsonaro supporters. What’s more, the only foreign lab authorized to sell the substance in Brazil counts Donald Trump as a shareholder.

In May, Brazil lost two ministers of health, after both refused to recommend the use of chloroquine. Since the last termination on May 15th, Brazil has had no one from the medical field occupying the ministry. General Eduardo Pazuello, an active duty military general, took over the position without any pertinent qualifications, triggering a flood of tweets in Brazil with the hashtag #cadeoministro (or #whereistheminister). The lobby for chloroquine went so far that a group of scientists from Manaus—who found in their research study that the medication may increase the rate of mortality for COVID-positive patients—received a legal inquiry from the federal prosecutor’s office and started receiving death threats.

The scenario is beyond chaotic. President Bolsonari has undermined quarantine strategies and encouraged people to go to demonstrations in his favor. The only way the government has managed to stop rising mortality rates was by taking down the official website that disclosed data about COVID-19. After 4 days of withholding information, a Supreme Court order forced them to publish the data again.

Brazil now occupies one of the highest COVID-19 diagnoses and death rates in the world, second only to the United States. But these statistics remain in question due to an issue of underreporting. Brazil has tested about 300 people out of each million inhabitants, while the U.S. has tested over 30 times this amount. The quality of imported test kits, three-quarters of which haven’t passed their origin country’s public health control requirements, have also skewed the numbers. A large portion of these tests came from a foreign supplier in China that had their right to export revoked, but, since the order took place before this mandate, Brazil received and distributed the test kits in spite of being fully aware of their inferior quality. Most of these fast test kits have a 40% chance of displaying a false negative result. Additionally, a patient’s cause of death can only be attributed to COVID-19 if they were previously tested, meaning those who have died from the virus but did not have access to testing remain unreported. It is likely that the number of infected people and mortality rate are significantly higher than the official statistics. Different studies by COVID-19 Brasil, a team of independent researchers from all over Brazil, have put together models suggesting that both the number of diagnoses and fatalities amount to less than 10% of total domestic cases.

The government’s relief aid is rife with controversy, too. The National Treasury provided informal workers 152 billion Reais (around 25 billion EUR) in additional funding, a very shy figure compared to the 1.2 trillion Reais (or close to 200 billion EUR) directed to banks on the grounds of maintaining the liquidity of the economic system, in spite of the fact that Brazil’s 4 largest banks recorded an all-time high net profit in 2019.

These issues with COVID relief have also trickled down to the local music scene. “Not only the funk scene, but the entire artistic scene has not received a single financial incentive from the government,” Leo Big Mix tells me. “The way the pandemic reached Brazil saddens me because I’m sure it could’ve been very different. The ones who could’ve done something did not. [The] social disparity here is absurd; the pandemic just made it much clearer. I figured it would take long, but at some point they would [think of us]. [But] we’re just left to our own devices.” He, like other autonomous workers, didn’t fit the aid criteria. But, in some cases, being eligible is not enough to receive support. Many claim to have had their aid denied even if they fulfilled the criteria entirely, without any explanation or a means to reapply. Others were stuck with stagnate statuses: The bank promised to inform the applicants within five days if they would receive financial assistance, yet their “in analysis” status remained pending for over a month. These issues have led applicants to queue at banks for hours, putting citizens at further risk of contamination.

At the end of July, Bolsonaro tested negative for coronavirus, and Brazil started a process of reopening from a lockdown that never really happened. In spite of over 90 thousand deaths, the president decided to reinstate air travel. The number of infections is rising again, but now even the people who were scared of contracting the virus are beginning to venture outside. The long quarantine has started to take a harsh toll on Brazilians’ mental health. “A lot of my friends and fellow co-workers had terrible breakdowns. I had a friend who had to go to an asylum. It’s a huge pressure to survive without work. The only help we get is from friends or NGOs. The community is sharing what it has so we can survive. If we wait for the government to help us, we will be left with nothing,” said DJ Polyvox, the founder of 150BPM baile funk. One of the few things that helped Polyvox get by during the hiatus was the National Copyright Collection Agency in Brazil (ECAD). Recently, many other producers started registering their music to maintain a passive income stream.

The government’s maladministration has made people choose between contracting the virus in order to financially survive or remaining confined with no hope for a solution. Leo is tentatively returning to a work routine and planning his next events, but it’s still far from enough to make a living. “I really miss my work pace,” he says, “I always liked working. I was on it from Monday to Sunday. I confess, I’m counting the minutes to go back on the decks.”

Max Folly is a Brazilian DJ and producer based in Berlin known as Folly Ghost. He’s also part of No Shade, a night club series and mentoring program. Follow him on Instagram.

Published August 19, 2020. Words by Max Folly, photos by Fernanda Liberti.