How Architecture Transforms the Clubbing Experience

Nightclubs have historically occupied marginalized and ephemeral spaces. Berghain in Berlin and B018 in Beirut are two notable exceptions to that rule.

It’s a nameless weeknight and you’re going out. You thread your way through uneven streets, dimly lit by glowing machines or humming streetlights, and you hear your final destination before you see it.

A crowd of people are waiting outside, blocking the entrance, their bodies turning together towards the doorway like dark flowers towards an unseen sun. The structures around you are ambiguous: a rolling tunnel of Victorian brickwork; or the anonymous façade of an industrial building; or a curve of metal fencing. In the line, a growing buzz of adrenaline grates against the stillness enforced by queue barriers. The friction results in tiny pockets of raised voices and jostling, bursts of laughter and the crunch of dropped glass. You reach the door and it’s always huge, and heavy, and faceless and encourages no second glances. You cross the threshold and wait again, this time in a narrow corridor, the humming bass peaking in spikes of vaguely discernible sound. You pay your entrance, give a hand or wrist through a glass partition to be stamped, and then suddenly you are moving. The corridor becomes a foyer and the mechanisms of control have seemingly disappeared and, all at once, you are in.

It’s an instant and jarring release into a kinetic chaos of bodies moving in all directions; between rooms, through doors, up and down stairways, colliding in constant motion between a booth or a bar or a bathroom. You move up and down ramps and past doorways through which the indeterminable sounds continue to move these bodies in different constellations of entanglement and distance, jostles and grinds. The spaces of the club collect you in different arrangements; from the communal spectacle of the dancefloor, to the semi-solitude of the cubicle, to the fluid mosaic of the smoking area until, eventually, you are spat back out of that entrance threshold into the same streets, now streaked with tired dawn light, where you started only hours before.

“Clubs are one of the very few types of architecture, besides maybe public bathhouses, which are so intimately involved with the staging and directing of human bodies interacting—sight, sound, smell, intimacy, inclusion and exclusion,” wrote Martti Kalliala, a trained architect and one half of electronic duo Amnesia Scanner, for Flash Art in 2016. Beyond the dance floor itself, the whole experience of clubbing is an intimately choreographed interplay of control and abandon, stillness and release, waiting and arrival—all mediated by architectural elements such as facades, walls, doors, stairways, corridors, and rooms.

And yet, for all this interaction between partygoers and the venues within which they dance, the role of the architect in the history of the nightclub—and, even more, the role of the nightclub in the history of architecture—is fairly ambiguous. Unlike houses, offices or public cultural projects such as libraries or galleries, few clubs appear in the portfolios of better known architects today (Arata Isozaki’s designs for the Palladium in 80s New York City being one glorious exception). Those who do work on club projects tend to be overlooked. The work is relegated to the practice of interior design, “[which] isn’t the most venerated form of architecture among architects,” suggests Kalliala, over the phone. “There is quite a lot of young architectural intelligence being deployed [in clubs], but it’s more behind the scenes.”

The history of gatherings around electronic dance music is thus largely populated by small design moves in improvised and adapted spaces—from the YMCAs and church halls of early-Detroit techno gatherings, through the occupied fields and warehouses of European rave culture, and onto the myriad industrial buildings repurposed as techno temples—rather than purpose-built cultural institutions. The reasons behind this are often tied into the broader politics of urban development. High profile cultural buildings, particularly in expensive Western cities, have been typically developed, built, owned, and run by socio-economic elites. Club cultures, on the other hand, have grown out of more marginalized communities; queer or trans people and people of color whose work did not fit into more mainstream spaces as a result of either exclusion or active rejection.

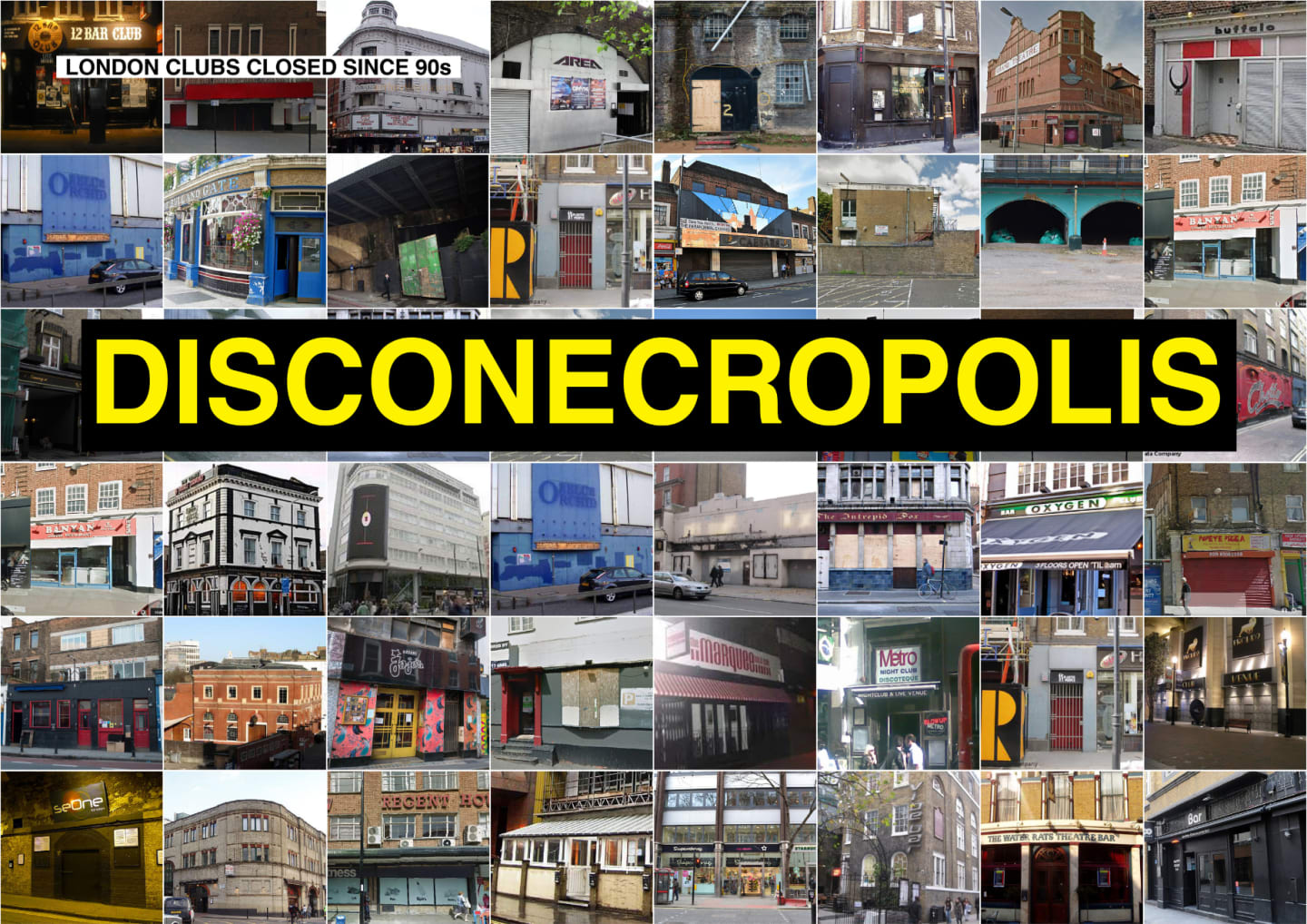

As a result, many influential nightclubs have occupied geographically and architecturally marginalized spaces, such as basements, railway arches, industrial zones, and have been defined by a particular ephemerality; few clubs last more than a couple of years in one spot. And while this short temporality does chime with the vital ever-changing nature of electronic music itself, the role of finance-led urban development should not be overlooked as a destructive force in contemporary club culture. London, in particular, has lost of dozens of nightclubs since the 1990s as a result of commercial developments; Dutch architects OMA dubbed the city a “Disconecropolis” (a necropolis being “a city of the dead”) in research for their now-cancelled renovation of Ministry of Sound.

Out of these conditions exceptional club buildings have, of course, emerged. Berlin’s Berghain is the obvious example and the one whose architecture occupies the popular imagination almost as much as the music played inside; the interplay between the rigidity of its interior/exterior threshold (the queue, the infamous door policy) and the contrasting fluidity of the spaces inside (the club has no dead ends) make for particular interest. More than this, the club’s location in a former urban dead zone, its scale, its occupation of an abandoned thermal power station, and the emphasis of that industrial history on its spatial design make it an archetype for contemporary club architecture—a precedent to today’s Bassianis, Printworks, and ∄, a new club in Kiev designed by Berghain’s architects Studio Karhard. “It was very clear that the Berghain building had a very strong atmosphere by itself,” explains Thomas Karsten of Studio Karhard, who have been making small tweaks to the club since its initial conversion in 2004. “It has a lot of industrial elements, the glass wall between the main dancefloor and the facade bar….those big windows at Panorama Bar. All these elements we wanted to save, so the main task was to fit all the technical needs into this building without destroying its character.”

Berghain also has the unique status amongst nightclubs of being well-known from its exterior alone. The obligatory post-set selfie or sneaky queue snap of the club’s facade render it visible as a piece of architecture, a monument like Big Ben or the Duomo di Milano. This recognizable facade and its relative isolation between Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain makes it readable as a whole building, in contrast to the spatiality of the typical club whose exterior presence reveals little of the interior, and which often is one part of a larger superstructure: an industrial complex or railway line, for example.

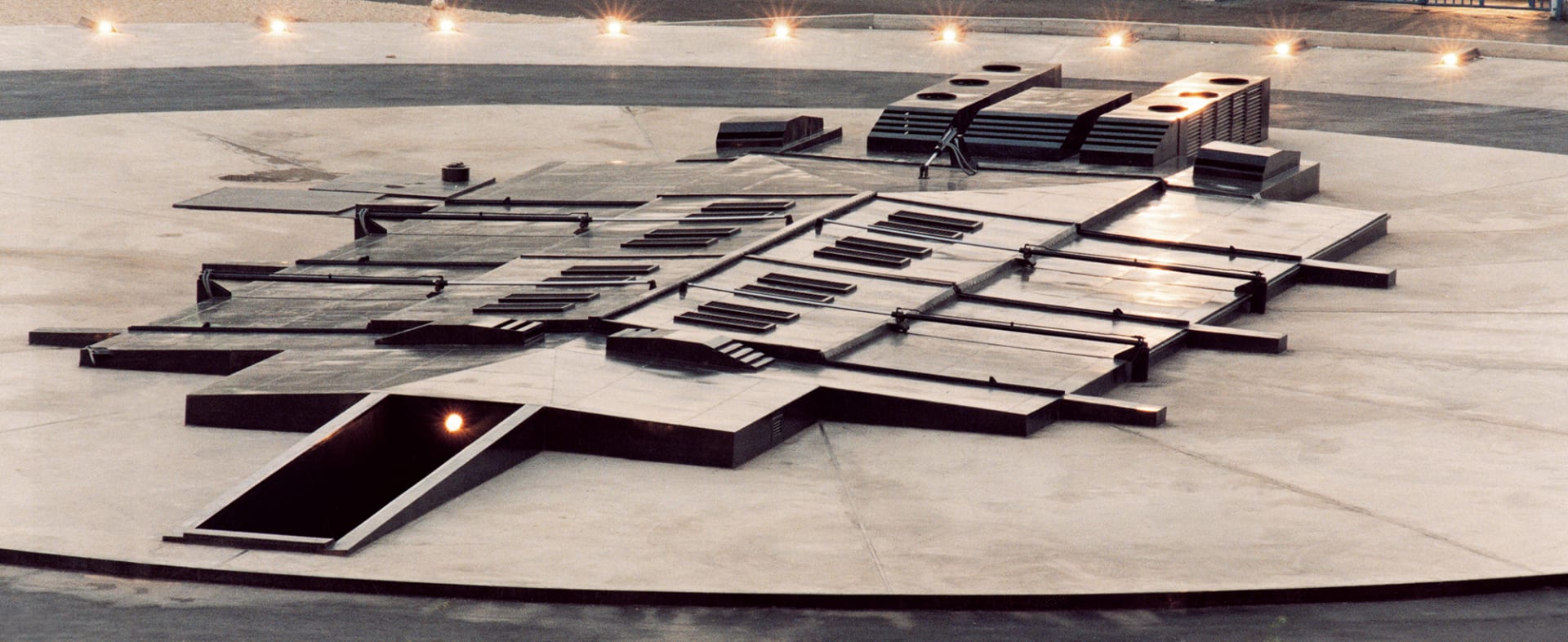

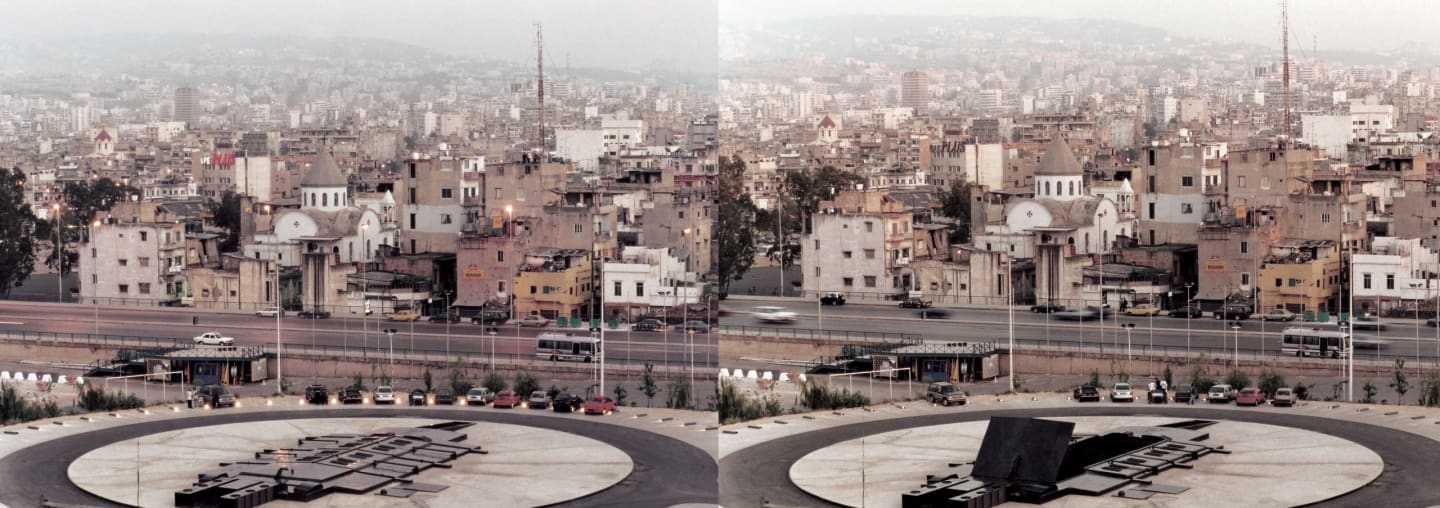

Another long-standing club, however, turns lack of presence into a design quality in itself. B018 in the north-east of Beirut was designed by Bernard Khoury, one of Lebanon’s best-known architects, in the late 1990s and continues to hold parties over twenty years later. As with the emergence of Berlin’s techno scene in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin wall, B018 appeared in Beirut at a time of significant urban transformation at the end of the civil war. Khoury sees his design for B018 as an intervention to directly confront the violent history of the city and site. “How do you build a place of debauchery on a site that has very deep, visible scars, in a period when the whole reconstruction efforts [of Beirut] were in complete denial?” he ponders.

“Unlike the other projects along the highway where B018 is, where everyone tries to be as visible as possible for short-term financial value, I decided to make a totally invisible project.” The club is a void—a crack in the ground with a sculptural but low-lying roof structure that lifts up each night, exposing the sunken dancefloor to the Beirut sky. At ground level, the arriving cars of party-goers create a circular geometry that extends the energy of the club beyond its underground interior and towards its surroundings. “The project has a very serious relationship to its site and its zone,” explains Khoury. “Clubs are never usually given an architecture, were never considered as anything worth investing architecturally-speaking. They are usually tucked underneath building. You rarely hear of a club that is given a serious architecture, or at least attempts to have some kind of political relevance.”

We can, of course, still read political relevance in the spatiality of clubs which eschew or turn away from their immediate contexts. While inherently wrapped up in the socio-economic realities of their contexts, nightclubs have also been seen as places to imagine and enact new ways of being together; imaginative places where social, gendered, sexual and other norms might be deconstructed or reframed. With this in mind, the deliberate lack of architectural interaction between the club interior and exterior can create a safer place inside, where the outside world can be temporarily banished. This is taken to an extreme at Hyperdub’s regular Ø night where room-scale installations, by artists such as John Akomfrah, Lawrence Lek, and the Otolith Group, are presented in one room, while DJs play in the other. “In some ways, a focus of Ø is imagining another future. A lot of the installations we host look at different strains and ideas around futurism,” explains Shannen SP, DJ and co-curator of Ø. “So the whole space needs to be immersive—down to the body-rattling sound system.”

What’s more,

a club clearly need not hinge around sheer volume like Berghain’s main

dancefloor to be spatially successful. The inverse to the techno-temple

archetype might be the dimly-lit sweatbox, such as London’s much-missed Plastic

People, where the spatial experience is defined by proximity, but also a

certain architectural myopia. Again, Ø, which is held at Corsica Studios is a

useful example of this. The room hosting DJs is often filled with dry ice, to

the extent that the crowd, DJ and, crucially, the space of the club itself are

obscured into a disorienting, bass-filled cloud. Similarly, during Amnesia

Scanner shows, Kalliala and co-producer Ville Haimala use stage technologies to

produce different spatial effects: “we’re not only interested in using strobes

or smoke as an image, but as something that you have to be fully enveloped in,

and maybe lose your sense of orientation in,” Kalliala says.

In its purest sense, these examples might be understood more as set design than as architecture, but there’s no doubt that these effects produce transformative club environments. They also demonstrate that, regardless of the architectonic sophistication or amount of raw concrete on display, the experience of clubbing will always be as spatial as it is sonic.

George Kafka is a London-born, Athens-based architecture writer and editor. Visit his website here.

Published April 27, 2020. Words by George Kafka, photos by Jon Shard.

Follow @electronicbeats