Why Are All Of These People Waiting In Line To Experience The New Infinity?

One fall morning in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district, a UFO-shaped white tarp landed on Mariennenplatz. Children began to run around and use the strange structure as a makeshift jungle gym, racetrack and climbing wall.

Mariennenplatz is a quaint square flanked on one side by the nearly 200-year-old church of St. Thomas, and on the other by the Kunstquartier Bethanien, which was originally built as a hospital in 1847. And between September 26 to October 14, it was home to a 16-meter-wide planetarium dome which accommodated The New Infinity exhibition. It was presented in partnership with Berliner Festspiele’s Immersion program and Planetarium Hamburg. The 100-person-capacity mobile dome was the follow up to March’s ISM Hexadome exhibition (which we reviewed here).

The event’s most remarkable performance was a closing showcase of “10000 Peacock Feathers in Foaming Acid”. The debut performance featured a collaboration between audiovisual duo Evelina Domnitch and Dmitry Gelfand, and ambient producer William Basinski. But it also hosted fixed media installations by Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, Fatima Al Qadiri and Transforma. Experimental video game maker David O’Reilly opened The New Infinity exhibition during Berlin Art Week.

The works on display produced stark contrasts. OReilly’s animation and the textured exploration by Al Qadiri and the Berlin visual art collective Transforma were much different than the quantum physics-inspired investigations led by Domnitch, Gelfand and Basinski. All three were unlike the short films created by Herndon and Dryhurst.

For project manager Marie-Kristin Meier, the value of The New Infinity laid beyond its context and diversity in Berlin. The works, she said, can be presented anywhere—in any planetarium across the globe. “I also think an important aspect is the possibility to reach out to new audiences,” she told me at the event. “Normally at the planetarium you don’t expect contemporary art.”

The New Infinity was promoted with the claim of bringing “new art to planetariums.” In a way, it did create a new context for multimedia art on an existing platform. As David OReilly expressed in his artist talk in the Kunstquartier Bethanien before the exhibition’s opening, “There was a strong feeling that this 3D stuff was not artistic, that it was too precise and that it couldn’t possibly be an artistic form. So that was a challenge that I became interested in.”

Presenting works like OReilly’s “Eye Of The Dream” furnished the planetarium with projections of dynamic, animated art. But it also established the suitability of showing OReilly’s work alongside short films like Herndon and Dryhurst’s Chain Opera.

The exhibition was a popular success in Berlin. More than 23,000 people visited over 19 days. Artists and young children alike filed into the big plastic bubble over the course of the exhibit. Children could be seen running around the structure and playing games on the steps surrounding it. At night, groups of friends gathered to have a drink and experience the eclectic selection of media on display. And it was free—for everyone.

It wasn’t only a novel experience for guests, though. For many of the artists, it allowed them to work with experimental projects of new proportions. “The most challenging part was to transport the image,” said Baris Hasselbach, a co-founder of Transforma. “You can create the atmosphere from a 2D image, but you never get the whole picture.”

With five projectors creating a 360-degree network of visuals, it was clear that the audience was not intended to see everything. Some projects, like OReilly’s, favored the middle of the dome, while others, like Herndon and Dryhurst’s, focused on only one section of the surface.

The setup also proved effective at creating an illusion of movement. But it was one to be explored with caution.

“There is a thin line where you get crazy physical effects,” Hasselbach told me. “Something is moving fast or slow, so you really get out of balance fast.” Once the eyes are concentrated, if manipulated, the screens can quickly elicit the illusion of propulsion.

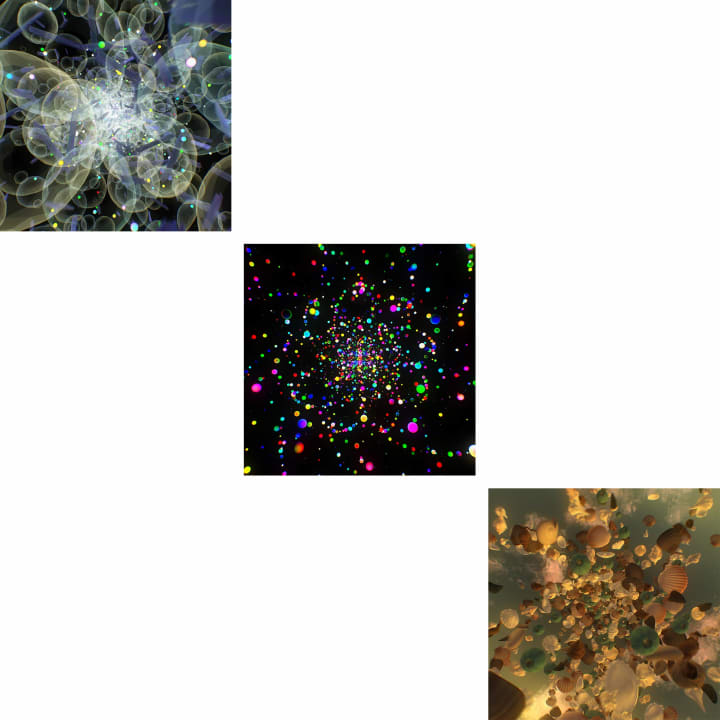

“You have to be careful on one hand,” Hasselbach said, “but you can also create a dense visual impact on the viewer.” While some works, like Herndon and Dryhurst’s, seemed slightly out of place on such a spherical stage, others like 10000 Peacock Feathers in Foaming Acid appeared to be created for this exact sort of environment. In the piece, Domnitch and Gelfand explored the geometric patterns of soap bubbles in water. When the light of lasers caught the bubbles’ edge, their behaviour was projected across the planetarium.

“[Gelfand’s] subtle and beautiful soundscape and sound manipulations live…it should be quite trippy!” Basinski anticipated ahead of the exhibition. “Think: ‘Music of the spheres.’”

As the most scientific and spacious of the works on display, it seemed the most appropriate. Instead of caving to the impulse to pack the screen with visuals, “10000 Peacock Feathers in Foaming Acid” was anything but dense. Instead, it gave the viewer plenty of time to appreciate the performance’s visual subtleties.

Domnitch and Gelfance are fascinated by quantum physics and have been crafting analog installations and other scientific experiments since the late 1990s. “There are some mathematical portals to the shape of our universe that are based on the geometry of soap bubbles,” Domnitch said in Berlin ahead of the exhibition’s launch.

“When one bubble structure collapses and another one arises immediately, it’s kind of an incredible feat of geometry,” she said. “I can imagine that [the audience] are looking at galaxies or into this infinity of the sky.” As the bubbles expanded and collapsed on the surface, the effect recalled a fusion of cosmic rainbows and the Aurora Borealis.

For Gelfand, work in the border realms of physics and classical art introduced opportunities for discovery. “Where you go from one domain to another and from one scale to another always interested us,” he said. “We think if you can catch this border, this razorblade age where the transfer happens, it kind of opens the door for you in understanding very deep things.” In the case of The New Infinity, the audience came along on their artistic experiment.

It’s impossible for two shows of 10000 Peacock Feathers in Foaming Acid to be the same. Due to the instability of the liquids, Domnitch and Gelfand can never predict the outcome of their work. But this seemed to be the most fitting part of their performance. In each venue, there were infinite possibilities.

The technology in Berlin’s mobile dome appeared more impactful than in Hamburg’s scenic planetarium. But despite the disparity, it was comforting to know that The New Infinity actually presented new artistic combinations that could never to be repeated.

After its dates in Berlin and Hamburg, The New Infinity will head on tour. In a much different context, it will visit festivals like Barcelona’s Mira and David Lynch’s Festival of Disruption in Los Angeles.

“It’s quite unique to open this institution of planetariums to artistic approaches,” Meier said. “There is a technology available all over the world and there are so many planetariums, but they are not really being used as tools for making art.”

Read more: ISM’s Hexadome is what immersive audiovisiual art has been missing

Published November 05, 2018.