A History Of Unsound Festival According To Co-Founder And Artistic Director Mat Schulz

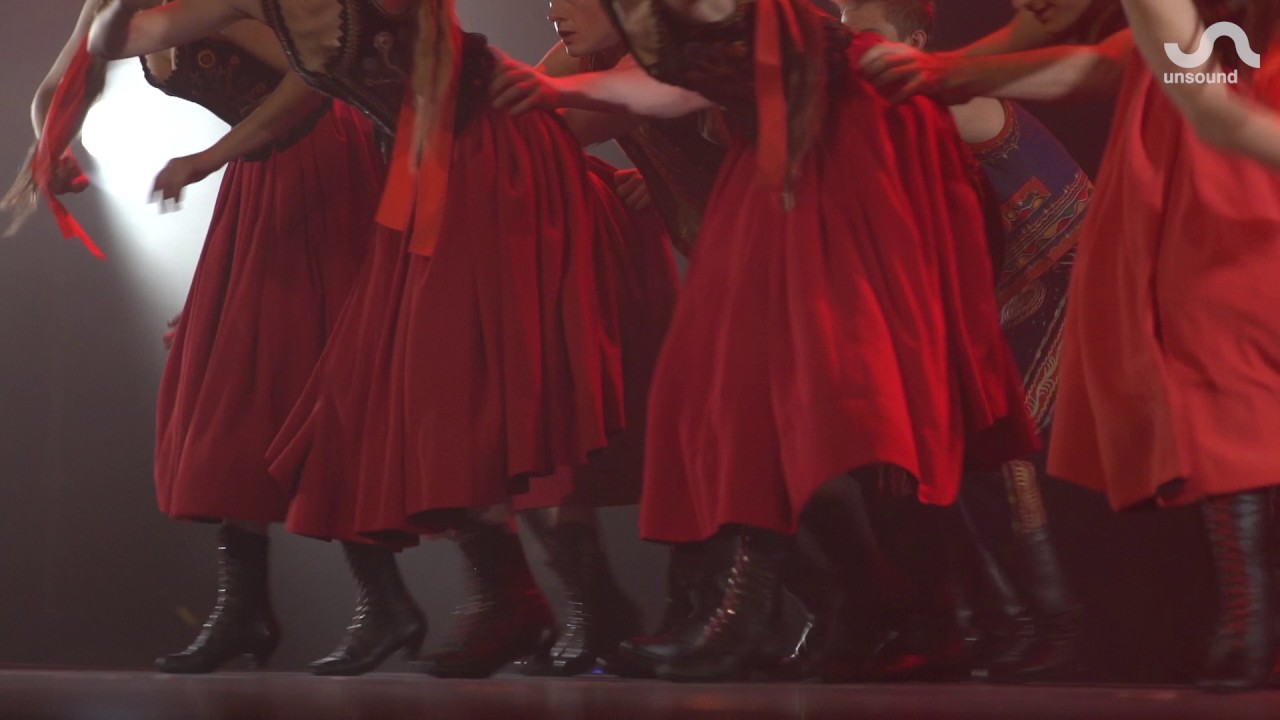

Over the past sixteen years, Kraków’s Unsound Festival has evolved into one of Poland’s most important cultural events, with an almost peerless reputation in Europe and beyond. The avant-garde music and visual art festival was co-founded by Australian novelist Mat Schulz in 2003, and he has been the festival’s driving figure since, overseeing the launch of satellite events in major cities like Toronto, London and New York as well as in smaller locations in Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Georgia.

This year’s Kraków edition of Unsound Festival is now underway. We caught up with Schulz to talk about the festival’s past, present and future, and we learned about his own ambivalent relationship with the festival.

[Read more: Our report from last year’s Unsound Festival Kraków]

When did you first arrive in Kraków?

I first came here in 1995, shockingly. I stayed for several months. I was studying Polish and had just had a novel published in Australia. I wanted to live somewhere in Eastern Europe and write. I was quite fascinated by the area that had recently opened up after Communism and the fall of the Berlin Wall. I was going to go to Prague, but it was already too touristy for my liking. Kraków was very raw and untouched at that time. I thought I’d stay for a little while, but one thing led to another, and I’m still here. I still go back to Australia for a couple of months when it’s winter here, and I’m very often travelling to different countries to put on other Unsound events.

How did the first Unsound come about?

I started the festival in 2003 with an American friend I was living with, Stephen Berkley. It was intended as a hobby, something small. Stephen and I were both into similar types of music at the time, and there wasn’t really any other festival dealing with this range of music in Poland. We thought we’d find some sponsors to pay for it, but that didn’t really work out. We’d go to these businesses in Kraków and ask for some kind of sponsorship or partnership, and instead we’d end up getting an offer to teach them English. So both of us paid for the first Unsound by teaching a lot of English.

What was the first Unsound like?

The first night was held at a small cellar venue called Klub Re. It was full, around 140 people. The second night we had about the same amount of people at another venue, but they kicked us out halfway through because they didn’t like the music. The third night it was meant to be at that club we got kicked out of, but we went back to Klub Re. Eight people bought tickets [laughs]. It was quite an experience, and neither one of us thought we’d do it again after that, patly because we lost a lot of money. But one thing led to another, a few people joined the team, and here we are.

Did either of you have a background in this sort of thing?

Neither of us had experience putting on events, so it was a trial by fire in a way. But you can learn a lot in a short period of time

How did you recover from that first year?

An independent curator working for the Goethe Institut got involved, but it remained a very local DIY event, basically, in these old cellars in Kraków for the first few years. Stephen stopped working on it after the second edition. The cast of people was always changing. It wasn’t until 2006 that Gosia (a.k.a. Malgorzata Plysa), now the executive director, got involved. She founded an NGO to run the festival, and we started to get funding from the city of Kraków. This allowed us to realise ideas that we’d had for a while.

Those ideas included expanding the festival internationally.

Unsound has always been very mobile and collaborative, both with other festivals and other countries. Very early on, in 2005, we collaborated with CTM Festival Berlin. In 2007 we took Unsound on tour, across borders. We went to Kiev, Minsk, Prague and Bratislava. The first Unsound in New York in 2009 increased our visibility internationally. Then, in 2010, we gave Unsound a theme for the first time—“Horror: the pleasure of fear and unease”—and all these things kind of combined to attract attention, to create a wider context.

That was a good thing, no?

In a way, Gosia and I were very ambivalent about the festival, in terms of if that was and what we wanted to do as a career. For me, I had my writing as well. Sometimes I found it quite frustrating that I didn’t have the headspace to write because it’s an important part of my life. And I don’t have too much time to do it these days. But I think this ambivalence was good in a way because it meant that we would take risks that we wouldn’t necessarily have taken otherwise. It’s always obviously good to take risks when programming a fesetival, and it’s easy to fall into a trap of not doing that.

Do you still feel that ambivalence now?

Yes, because I’m still not writing much. I did finish a new book actually, but I haven’t published it yet. It took quite a few years because I was mostly writing it when back in Australia. It’s quite funny, how things have reversed. I moved to Kraków from Australia to write, and now I do most of my writing when I’m back in Australia.

What’s the book about?

It’s a memoir set between 1995 and 2005 about moving to Poland and kind of moving back to Australia for a few months each year and the weirdness of that. But it’s not about Unsound, there’s nothing about Unsound in there.

Why Unsound, anyway? Where did the name come from?

There was another version of Unsound in Wagga Wagga—in regional New South Wales, Australia—started by friends and my brothers. That started a year or two before Unsound in Kraków. It went for one or two years then stopped, and the Polish version kept going.

How many tickets do you sell to the Kraków edition these days?

Over eight days, we have about 25,000 attending Unsound. The smallest venues might host 150 people, the bigger venues could have up to 2000 people going through them over the night. We could sell a lot more passes, but it would mean going into bigger spaces. That would change the program and the atmosphere.

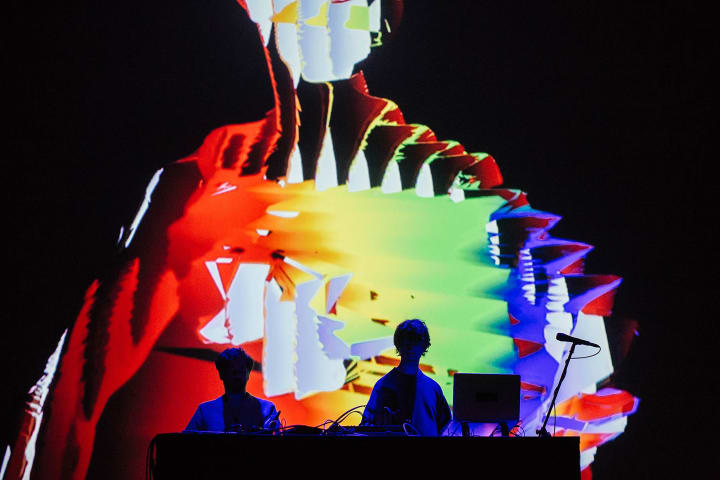

There are examples of other festivals that have gotten bigger and lost the thing that made them unique. So it’s very much been a conscious decision to not grow beyond a certain size. At the same time, we began thinking about other ways the festival could grow, and we started commissioning projects. We develop projects and tour them, working with artists like Jlin and Robin Fox, and also developing events in other cities. In Toronto we held Unsound at a power station with eight thousand people, but we don’t have that sort of space in Krakow. More and more, we’re using the platform of Unsound to develop different ideas and projects.

What’s the local to international ratio of attendees?

I’d say around 50% of people buying tickets are from other countries, the rest are people from across Poland. After Poland, the next biggest country in terms of attendance would be the United Kingdom. We try to not make it too expensive because we obviously want Polish people to come. It has to be same price for everyone, that’s really important, and we also set tickets aside for the club nights for locals. There are a lot of free events, too. The discourse program from 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Monday to Friday, all of that is free. The closing party is usually free too, and we have free concerts. The Morning Glory concerts at 11 a.m. are always free. A big part of the festival is to make it accessible and inclusive, so it’s important for us to have all these free elements too.

Unlike at other festivals, at Unsound it’s possible to attend pretty much every event in the program without missing anything, right?

It’s still pretty much the case. If you come at the start of the week, you can go to pretty much every event. We don’t really have two events on at different times. Maybe it happened once last year, but generally there are no clashes. Except for at the club nights at Hotel Forum, where things are going on in different rooms at the same time, so you might have Polish jazz going on at the same time as club music upstairs. It makes a really nice contrast. It’s important for us that people have the experience of moving around the city and going to different venues. I’m really interested in the idea of how architecture and spaces change when you put a show on there and how it works in acoustic terms.

What’s your booking policy?

We’re always looking for new artists, newer strains of music or genres or subgenres that we find interesting. This gets harder, navigating your way through all of that, as it seems to come at an accelerating rate. There are more and more festivals as well, and ways we would have programmed the festival several years ago that might have been radical are not so radical anymore. We’re constantly thinking of ways to make it unique in terms of the way we present things and what we present together. In some ways that’s easy to do, and in some ways it’s quite hard. You kind of need the anchors of things you know in order to experience the things you don’t know. Each year we also try to commission projects, develop projects or present new projects connected to the theme.

You do have certain artists who return regularly though.

I don’t think of Unsound simply as a festival but more of a platform in some ways. In terms of its relationship to certain artists, it’s also like a label. We’re very happy to invite artists back who are doing something new and different, especially if we’ve been working with them from the start, like Jlin. Gosia is her manager, and we love her music. Tim Hecker is another one. He was part of Ephemera, the sound and scent project we produced, and we also developed a live show with him. Another good example is Ben Frost, who we’ve worked with a lot. Just last week we were working with Ben on the recording of a film score for the newest series of [TV series] Fortitude. He wanted to record with Polish jazz musicians. We put together a big ensemble, and we recorded in Warsaw.

Do you adapt the concept of Unsound depending on where the events are held?

Not really, but it does tend to change depending on the location. A big reason we did Unsound in New York was to bring artists from Poland and surrounding countries and create a context where they could play alongside better known artists, and people would come to a show who might not otherwise. To give another example, the experience of putting on Unsound in Tajikistan was very different to doing it in Poland. We had to move a bunch of artists from Friday night to Thursday night, as the club said we would scare away their regular weekend audience. That was one of our Dislocation events [Dislocation was the Unsound theme for 2016 and 2017, with satellite events held in Kyrgyzstan, Georgia, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine]. Some of them have been amazing. Some have had problems pop up that you wouldn’t expect. But it’s been a great thing to do, bringing this music to places it wouldn’t otherwise get to, for the artists, and the audience. It’s also good for keeping perspective on things. People think it’s the same everywhere, but it’s not true at all.

Is it true that only 50% of your revenue comes from ticket sales?

Tickets are less than 50% of revenue actually, the rest is city funding and regional funding from Malopolska, the region we’re in. We haven’t had any funding from the Ministry of Culture for the past few years since the government changed. We do get some EU funding. Unsound is quite unbranded, let’s say. It’s been quite intentional, but it gets harder to produce the festival without working with sponsors. Putting together the festival and keeping it on the same level with the same budget is quite a struggle. It’s more Gosia’s side of things rather than mine, but it’s not easy to do. It’s true of all independent organisations that run festivals.

It’s testament to your curatorship that people will buy tickets even when half the lineup is a secret, as was the case in 2015 with your “Surprise” theme. How successful was that?

I think it was Ben Frost who suggested that we just don’t announce the lineup. I was thinking for a while, “How would that work?” I thought it would be too much, so we announced half of it. A lot of the program is a surprise anyway to some people, so the Surprise theme was just taking that one step further. In terms of concept and execution, it was one of my favourite Unsound festivals.

You banned phones one year too, right?

There were phones. It wasn’t enforced but rather strongly suggested that people don’t use their phones. We didn’t take any photos, and we didn’t let media take photos. We had people drawing the shows, so that was done instead of photography that year, basically.

It kind of ties into your theme of “Presence” this year, too.

It’s almost quaint to think of this photo ban just a few years on. And Presence is related to technology, yes. We don’t want to say this is bad or that is good, but rather ask how do you relate to technology and use it, and how does it affect you?

For more information about Unsound festival, visit its website here.

Published October 08, 2018.