The article you’re reading comes from our archive. Please keep in mind that it might not fully reflect current views or trends.

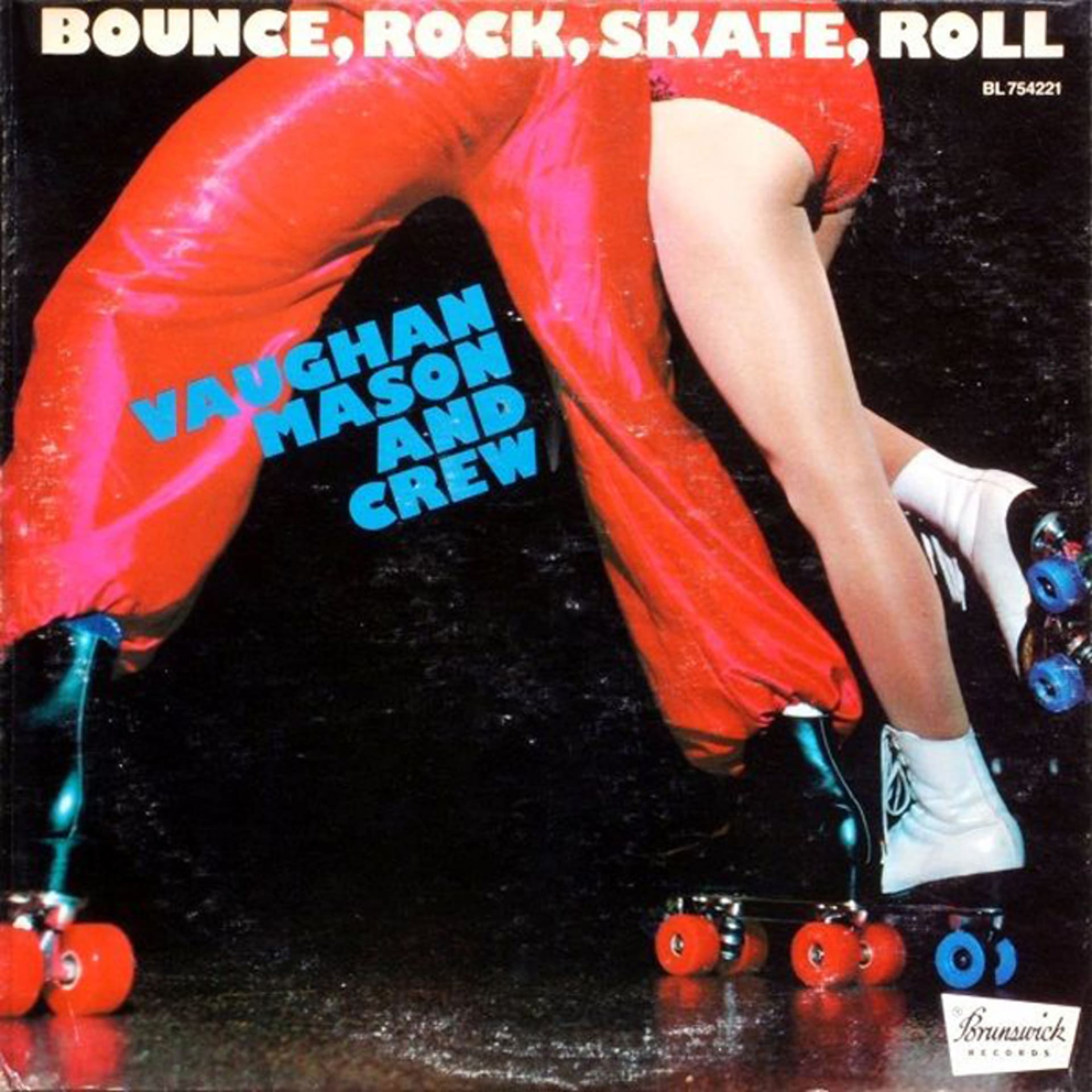

Vaughan Mason’s “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll” Story

Last month, we revealed part one of our in-depth feature on African-American roller skating communities, and before we unveil the second installment, we’ve decided to roll out an exclusive interview with one of the rink music’s most charismatic characters: Vaughan Mason, the mastermind behind the hit single “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll.”

Historically, thematic roller skating songs, even the best ones, have often been driven more by opportunism than artistic afflatus. The most famous rink burner, Vaughan Mason and Crew’s “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll,” was the product of the frontman’s entrepreneurial verve, scientific approach to constructing pop hits and the pressure live up to his family’s high expectations. His father, Vaughan Carrington Mason, was a famous OB/GYN who delivered the children of Thurgood Marshall, the first black Supreme Court Justice in the United States, while his sister became a Harvard lecturer. The Mason agnate rose to the family’s standard by creating a number of legendary singles, including “Roller Skate,” “Big Jammin’ Guitar,” “Smerphie’s Dance” with Spyder D and “Break for Love” with Raze, all of which have been sampled to death. As Electronic Beats’ print Editor-in-Chief A.J. Samuels discovered, the origin story behind “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll” is as eccentric as its creator.

VAUGHAN MASON: So, I’m working at a stereo store on Trinity Place, about four or five blocks down from the World Trade Center. This is the summer of 1979. I was living on my friend’s couch, and I was making about $125 a week. A friend of mine from Yonkers had just graduated from the Wharton School of Business in Pennsylvania, and was telling me about stocks and explaining how money works and all that. He said, “Why don’t you just get a Wall Street Journal and watch some penny stocks?”

So here I am making $125 a week and I have a Wall Street Journal under my arm, riding the subway from Brooklyn to Manhattan. On the front of the Journal to this day, there’s a section called What’s New, and that day there was an article that said “The industry is selling 300,000 pairs of roller skates a month.” I said, “There’s no way I can go wrong writing a song about roller skating!” Previously I had been a recording engineer, and was managing a band in the Washington DC area. Prior to that I went to Howard University, but I dropped out in 1972 when my father passed away. I’m digressing a little bit, but the catalyst for being into music was the Beatles. When the Beatles came out I was living in a white Jewish and Italian neighborhood in Yonkers, New York. I used to stand in front of the mirror and just wish and pray to God, “Why can’t I just have straight hair so I can shake my head and have everyone go ‘Hooo’ like the Beatles?”

Anyway, when I had the idea for the song “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll,” I first went to the Empire Roller Rink, stood on the side, and watched and listened. Anybody that was teaching someone how to roller skate would be skating backwards, and they’d be holding the hand of the person that’s trying to learn. They’d say, “Come on, bend at the knees, bounce.” That’s where “Bounce” came from. “Rock” was probably the laziest dance in the world; it was basically like doing the twist without moving your feet. That was a hot dance and everybody was doing it, so “Rock” stayed. “Skate” and “Roll” were easy. Musically, I’d also go to a club in Manhattan, Club Leviticus. I’d be listening and think, “This music, there’s nothing to it. It’s just guitar, bass, drums, another sound—either synthesizer or string—and a vocal, but these people are going crazy over this stuff.”

See, making music wasn’t about what I like; it was just a business thing to me. So I said to myself, “Let me go about this like a business person.” I bought a Billboard magazine for the month of July and looked across every chart—pop, the Hot 100, the R&B chart, the dance chart, then club and radio play, and then 12″ dance sales—looking for whichever song appeared in the top ten of each of those charts. Whether I liked the song or not, that’s the song I was going to pick as a model for a new single. “Good Times” [by Chic] fit those criteria.

Not being a musician, I basically got a paper and made a line like a goalpost down either side of the page, and then connected it going across horizontally. Each one of those from left to right would be eight measures, and then there would be a line that would be 17 to 24, 25 to 32, and so on. I sat there and listened to “Good Times” and counted out the bassline from that entire record. It was on one and three. So right on my first line on the left-hand side I wrote “Kick: one and three.” I went to the snare drum and I did the same thing, two and four. That’s what I did with the whole song—with the strings, the guitar, the piano, the Fender Rhodes—when they played and when they dropped out. I mapped out the whole damn thing—it took about five pages—and that’s what I went into the studio with.

I called my friend at Arrest Records, where I used to work in D.C. I said, “Listen, I’m coming down. I’ll bring the drummer, you play the keyboard. I need a guitar player, a bongo player, and a male vocalist. I’m coming on whatever the weekend is, let’s do it on the graveyard shift.” Because I only made 125 bucks a week, I flew down on the Eastern Shovel—that’s how far back that goes.

I get there, meet the guys, and I tell everybody, “I have $75 to pay you each, and I’ll give you first right of refusal to go on the road should this song take off.” The only people that took me up on it were the lead singer, Jerome Bell, and the drummer, Gregory Buford. Everybody thought I was absolutely crazy and when I met them down in DC, I said to the lead singer, “While I’m recording all these drums and all these other instruments, you go in the back. I need a verse about roller skating and a verse about dancing and a verse joining the two together.”

I made acetates of it once it was done—and they were expensive—from Sunshine Sound. I only made three of them because it was expensive. I’d walk around at night to different clubs that were hot in New York and talk my way past the bouncer. I’d tell them “I’m not here to have fun, I just want to give this”—and I’d hold up the acetate—“to the DJ and then I’m out of here.” So the guys would let me in.

Back then, the DJ booth was really high up and I had to reach and get the edge of the record over so that the guy could see it, and this hand from nowhere would come out and take it from me. If that DJ, whoever he was, played that record within the first half hour, I walked out of there and moved on to another place. If he didn’t I asked for it back.

I tell musicians and people all the time: feel the feel. Making money in the music business is not about the music, it’s about the feeling people have from what you’re playing, and what you’re playing will get to people faster if it moves like a record they know. When a DJ’s up in the booth and the dance floor is packed, people will say “Ah, he’s up there jamming.” No he’s not. He or she is up there—well, back in the day, today they’re just looking up names on a computer—looking for a song that either keeps the same number of people on the dance floor or adds to it. To this day, it’s human nature that if you hear something new, especially if you’re a dancer who just goes to clubs and wants to dance, you want to feel that same vibe. And that’s what letting a song feel like a hot record which is out already—almost like a remix to the damn thing—does. People will stay on the dance floor and think, “Yeah, I like this.”

But to convince people that it was something special, I stripped out of my usual schmuck clothes and became a cartoon character. I put on my boots—my boots were up to my knees—and black tights. I had a pair of Rooster underwear briefs, and then I had on a cape, a gold cape! I wore that shit out of the house and I became that person. When I was around the 50s of Manhattan on the West side, some girl came up to me and said, “What are you doing?” I said my usual line: “I’m an entertainer, I’m looking for financial help, can you help me?” She walks me up the street to Charles Huggins at Hush Productions. He hears the record and immediately says, “I’d like to sign you on as your manager. We’ll take you around to all the clubs that you’ve been to in the limousine, and just work it that way.”

We signed a preliminary management agreement, but I kept going to clubs on the weekends and giving out more acetates. The label on the record said “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll – Vaughan Mason” and phone number. Charles took it to every major record company, from Motown to Polygram. Meanwhile, I’m just doing my thing, and at 11 at night I get a phone call. There’s a lot of music playing in the background and a guy says “Hi, I’m Ray Daniels. I’m Vice President of Brunswick Records. Do you have a record deal?” I said no. He said, “The DJ has been telling me about this record for a long time. I just saw it happen. They put that record on, and the dance floor got ass to elbow. Can you be in my office tomorrow at 11 o’clock in the morning?” I hung up the phone and I was hitting Mariah Carey notes; I was screaming at the top of my lungs and I hurt my throat. I was screaming that loud because I’d followed through with something, and it had worked.

The song was not even supposed to be called “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll.” The name of the record was going to be called “Vinzerelli Bounce” because Vinzerelli was a big roller skater and very popular at Empire. We chatted a little bit, and he said that he played the soprano sax. I actually flew his ass down, just before I got the deal, to Washington and Arrest Records and recorded him doing a sax solo during the breakdown. It got nixed, but that’s how close the song got to not being called “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll.”

The band wasn’t supposed to be “Vaughan Mason and Crew” either. I need to kiss—and unfortunately I can’t because he passed away three or four years ago— Ray Daniels’ ring. I wanted to call the group the Truth, and I’m so glad that he said, “Let’s call it Vaughan Mason and Crew.” I’m not an egotistical person so I wouldn’t have named it after myself, but I went along with anything they wanted to do. My biggest mistake, in retrospect, was that I did not have them put my face on the cover of the album. It didn’t matter though because “Bounce, Skate, Rock, Roll” became the national anthem. The first time I heard it was coming down the alleyway from a record store. Brunswick shipped the records out on Greyhound and Trailway buses. You could ship anything on a Greyhound bus. That’s how Brunswick was getting those records out so fast. They shipped them all over the place.

For my next song, I thought, “If this horse is winning…” and I did a song called “Roller Skate.” Jerome Bell sang on it, and I thought of that bassline coming back from visiting my sister in Boston. I’m not interested in being the person that has to play a song—that’s too time consuming to learn how to do it really well, so I hired other people. I don’t think you’ll ever see Donald Trump with a fucking hammer in his hand. “Roller Skate” started going up the charts and doing well on Billboard, until Billboard found out that Matt Turnpole’s partner Jerry Kenney was hyping the numbers. They were saying it was a single when it wasn’t, and that made the numbers plummet. I remember Bohannon walked in there once wanting his fucking money and threatening people and shit, and the very next day there were Louisville sluggers in everyone’s office and some big Italian guy from Brooklyn hanging around to fuck him up.

Anyway, “Jammin’ Big Guitar” was my next single, and on that I took apart “Another One Bites the Dust” by Queen—that’s the formula I used. It’s just a song about a dick. It started off being something else, but it got to a swinging dick: [sings] “Now feel my big guitar.”

Then I became the opening act for Prince and Rick James on the Fire It Up tour. I was travelling all over the United States, playing every major coliseum of the day. I didn’t have any relationship with any kind of roller skating rink, but I did appearances as Vaughan Mason. But I can’t fucking skate, you know what I mean? They wanted for me to have flames coming out my ass and doing tricks, and that wasn’t in the plan at all. On tour I did learn to roller skate. I still have the roller skates and skate every once in a while.

Click here to check out part one of Electronic Beats’ feature on roller discos.