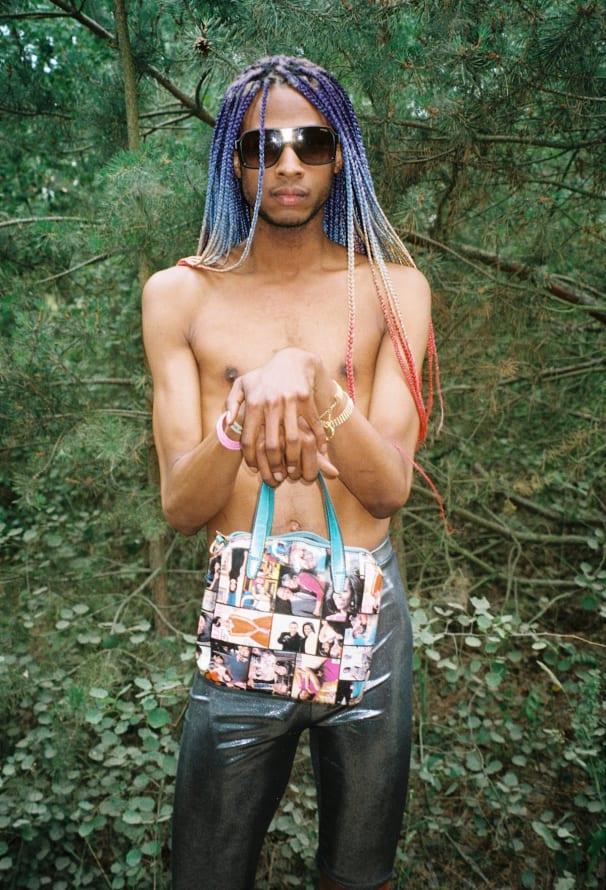

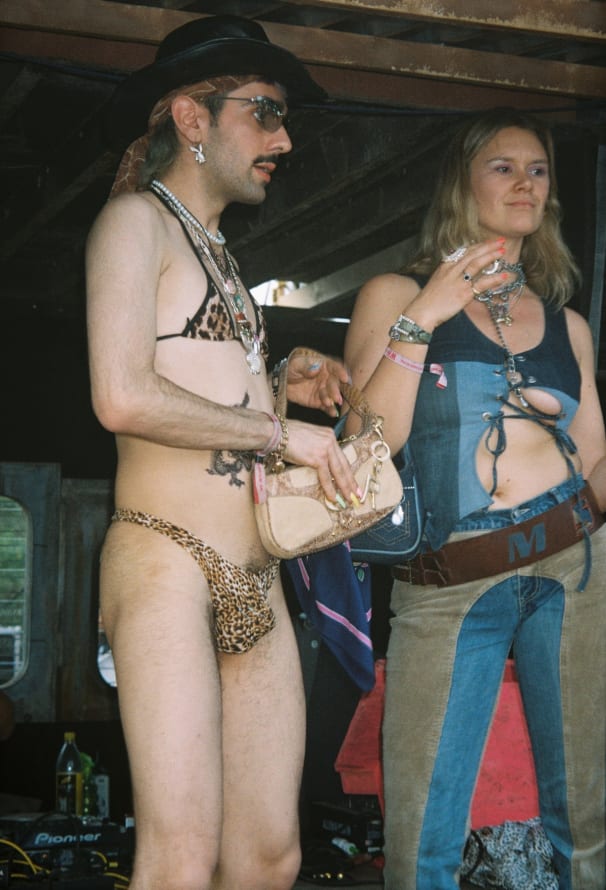

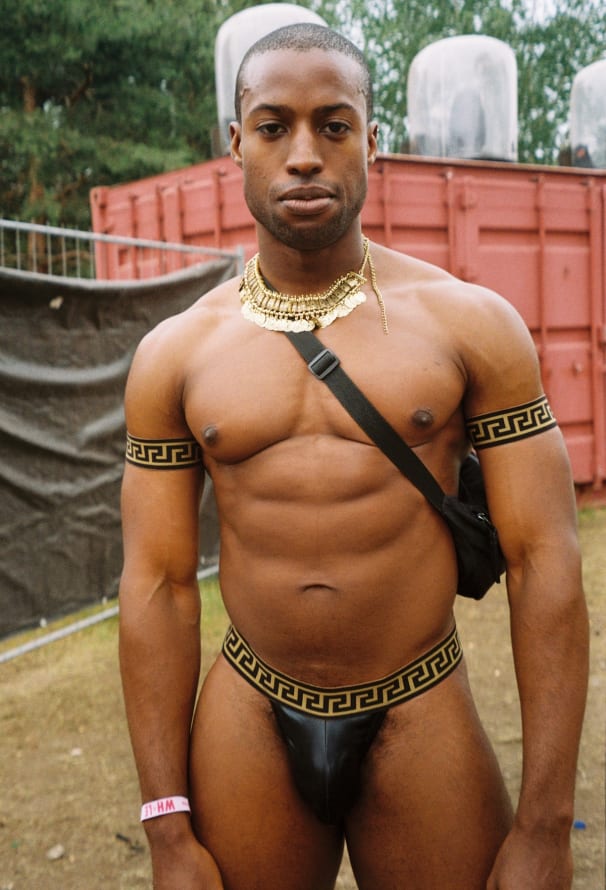

Club Histories and Geographies at WHOLE, A 3-Day Queer Music Festival In Rural Germany

We talked with Buttons' Jacob Meehan about WHOLE Festival, a new queer event held in the countryside near Berlin.

WHOLE United Queer Festival’s first edition in 2017 consisted of eight party crews from Berlin converging on the shores of the Bergheider See lake in nearby Brandenburg. Two years later, WHOLE drew together 28 crews hailing from a few different continents. Along with a wider geography represented on the bill (stretching from Mexico City’s performative unit Traición to a handful of residents from Tbilisi’s Bassiani club), the festival’s ambitions have expanded: a growing program of workshops, installations and panel discussions accompanied the music, providing a counterpoint of theory and discussion to the sweaty, kinetic practice going down on the dancefloor. A week before this year’s festival, poet and TEB contributor Nat Marcus spoke to WHOLE Festival organizer Jacob Meehan, who is also a resident DJ and coordinator of Berlin’s Buttons party, thrown monthly at ://about blank.

We can definitely agree that what it means to be queer in Mexico City is different than what it means in Pittsburgh or Tbilisi. So what, then, does this term “queer unity” mean to you?

JM: It’s definitely something that we reference a lot – and so we ask ourselves, “How do we embody this unity?” In no way is it a definitive statement, so we listen to the people that have been involved the whole time or people that joined in the past years. So it’s kind of an extended network. I was thinking today before I came—Buttons has a mutually supportive relationship with Unter in New York; they’ve done parties in Mexico City with Traición, who in turn have come to Berlin and collaborated with Room 4 Resistance; R4R work really closely with Mina; Mina organises events with Lecken…

What seems to prevent it from being cliquey is that it’s a network whose connections are open to branch out further. Like this expansive, expanding nebula of freaks.

The festival also isn’t just a bunch of collectives that have DJs – everyone’s pretty self-mobilized. It’s really about a group of organizers; everyone carving out their own little niche in their city and providing something that otherwise didn’t exist.

Is there a gap or a hole that WHOLE is filling as this kind of composite entity? I’m not really a festival girl, so I don’t know about the organization of these events.

There are others, for example the Queer Festival in Heidelberg, which is turning 10 this year. But it is a kind of new idea to bring this diverse group together for an entire weekend, camping, displaced outside of the city, being one in nature. And still there’s other examples of that—there’s the Honcho Campout in the US. But I think the scale of WHOLE is unique too: rather than some huge 25,000 person festival, 3,000 people are camping and kind of butting up against one another, mixing together. Which goes back to the idea of what “queer unity” could be…

There’s always an ambiguous relationship between the political reality of the club and the otherworldly, spiritual unity it can foster. You have Terre Thaemlitz on the one hand, who takes a really anti-spiritual approach, and sees in club culture’s messages of spiritual unity something that whitewashes or wipes out the differences of individual experiences that constitute this very culture: what it means to be a Latino gay man going to a club in the ‘80s in Chicago is different than what it means to be a white trans woman going to a club in ‘90s New York, or the ‘00s in Berlin, etc. But then you have someone like Eris Drew…

Who played at WHOLE 2018…

Yes she did! I mean she frames her practice as shamanistic, mystical. I saw on the program for this year’s WHOLE there’s a Gnostic mass ritual. So where do you think spirituality fits into the equation?

I think that you’re kind of signing up for it, or at least somewhat open to it, if you’re signing your time over for an entire weekend—commuting a couple hours and bringing temporary shelter. You’re kind of going through the motions of surrendering yourself to a willingness and openness to connect, or to be a part of a greater conversation. Obviously I can’t speak for every person’s spiritual motives, but I think it’s there.

I mean I don’t fall on either side of the equation: I believe in the kind of criticality with which Terre Thaemlitz approaches this history. And I feel we should, she’s been there, she knows what she’s talking about. But at the same time I really feel the spiritual unity.

I mean the music alone is capable of doing that. An organization called the Chicago Gay Liberation Front was responsible for helping organize Chicago’s first Pride March in 1970, one year after Stonewall, which was in June that year. But in April they also organized a dance: it was the first public dance organized by a gay organization that wasn’t tied to a university, so it didn’t have the security of an institution. There was a lot of trouble getting a venue and finding someone to insure them, but in the end they pulled it off. Reading this history has made me think that we’ve made a lot of progress, but it’s still so much the same struggle.

One always has to comb these histories in hope of finding something new. Or something repeating—I mean with the idea of a festival, you can go back to the multi-day parties Spiral Tribe was doing in the farm fields of the UK in the early ‘90s. But you can also go all the way back to the Dionysia in ancient Athens. There, in addition to the music and drinking and craziness, a central part of the proceedings was also the performance of Attic tragedy plays. And so I found it interesting that there’s a dedicated part of the WHOLE bill that’s for performance.

Yes, on Friday night and Saturday night. And a collective like Traición actually has someone performing in the middle of their musical sets. I didn’t even know this about them until I was researching, but their party is really rooted in performance art. They have these moments that punctuate the party.

It makes me realize too, that it’s not something we experience so often here in Berlin. I remember performances going down at Buttons, with an opera singer.

Oh yeah, yeah he’s performing at the festival—Ludwig Obst.

And then Lakuti and Tama Sumo have brought in the drag performer Kalypso Bang to their Finest Friday parties as well. It’s really refreshing to see, because it disrupts the format of a club night.

That’s something I realized when I moved here to Berlin. A lot of parties have the same kind of makeup: roll up to the club, program the DJs, that’s it. I feel like in the States there is still a more common tradition of performance in the parties; I mean at least a queen is going to get up there and do something. I used to be involved in throwing parties in Chicago at the Bijou Theater, which is now closed, but it was the oldest gay porn theater and sex club in the city. Having that theater space really taught me a lot. The space was built in 1969 or 1970—so think about this kind of pre-AIDs era in which men were all the more willing to go out and have sex with each other, but it was still very “nooks and crannies”. So there wasn’t a lot of room to work with beyond that theater stage, but that allowed us to program the music differently and change the whole structure of the night.

And how is it for you approaching a space like Ferropolis versus ://about blank? Nightclubs in general are space with some of the most kind of particular attention lavished on the sensory information presented in their environments—of course the sound, but also the lighting, temperature, smell and how the architecture is utilized.

On-site you have to learn how to adapt all of it on a different scale. We have two building teams and a tech team, an entire production staff and a ton of eager volunteers that help us get everything in place. We’re going do the floating stage again—but of course that requires a separate company to come and build a platform in the water. Someone was complaining on social media today that the festival is capitalizing on queerness, but I kind of thought to myself, “Oh, you don’t even want to know how much energy and resources we’re putting into this”.

This is a critique that will always be (and maybe must be) lodged at any kind of commercial entity that makes queerness a part of its identity or ethos. But if what that word stands for is such a central part of the festival’s existence, it’s animating ideal, what else are you gonna say?

It’s an easy critique to make, but if you dig deeper, you can’t deny all of the important work that every single one of these collectives is doing in their own scenes and their own cities. Even the different groups from Berlin—each one has a distinct mission and a different community they’re nurturing. One I’m most excited about is the House of Living Colors, which is curating the Friday night performance stage—all femme, trans, non-binary people of color, a group that stemmed out of not feeling welcome on many performance stages.

Do you think it’s possible for there to be political potential in the festival?

I think so. This is the first step – you’ve gotta be together and share space and have conversations.

It seems like that next step can be such a hard thing to manifest though. What do you do to keep that energy of the festival rolling forward? And what do you think is the political potential of a club or a festival?

Of course there’s the very act of it all: I think sharing space allows for conversations to be had.

And yet it’s not a united queer conference—it’s a music festival of international collectives.

But I want to turn it into more of a conference.

Okay!

Not entirely. But this year we’ve added some panel discussions, because we realized it’s going to be a huge missed opportunity if we bring everyone together and then there’s no time to sit down and just talk. Not just dancing next to each other and appreciating the music together, but also having some full-fledged conversations where we can share our experiences and exchange knowledge. So is it going to turn into an actual conference? No. But I like flirting with this idea of turning it into a kind of summit, because we need to exchange ideas and check in with each other. We want people to come who may not even give a shit about electronic music. But maybe they’re gonna come for the performances, or the workshops, or just to spend some time outside the city with a group of people they feel comfortable with.

We can have a discussion, listen to or sit on a panel, and then later we can go wild out together – and we can learn from each other in that way too!

It also goes back to this discussion of “unity”—there isn’t just one type of queer, so we want to provide for more than one taste.

Published July 10, 2019. Words by Nat Marcus, photos by Spyros Rennt.