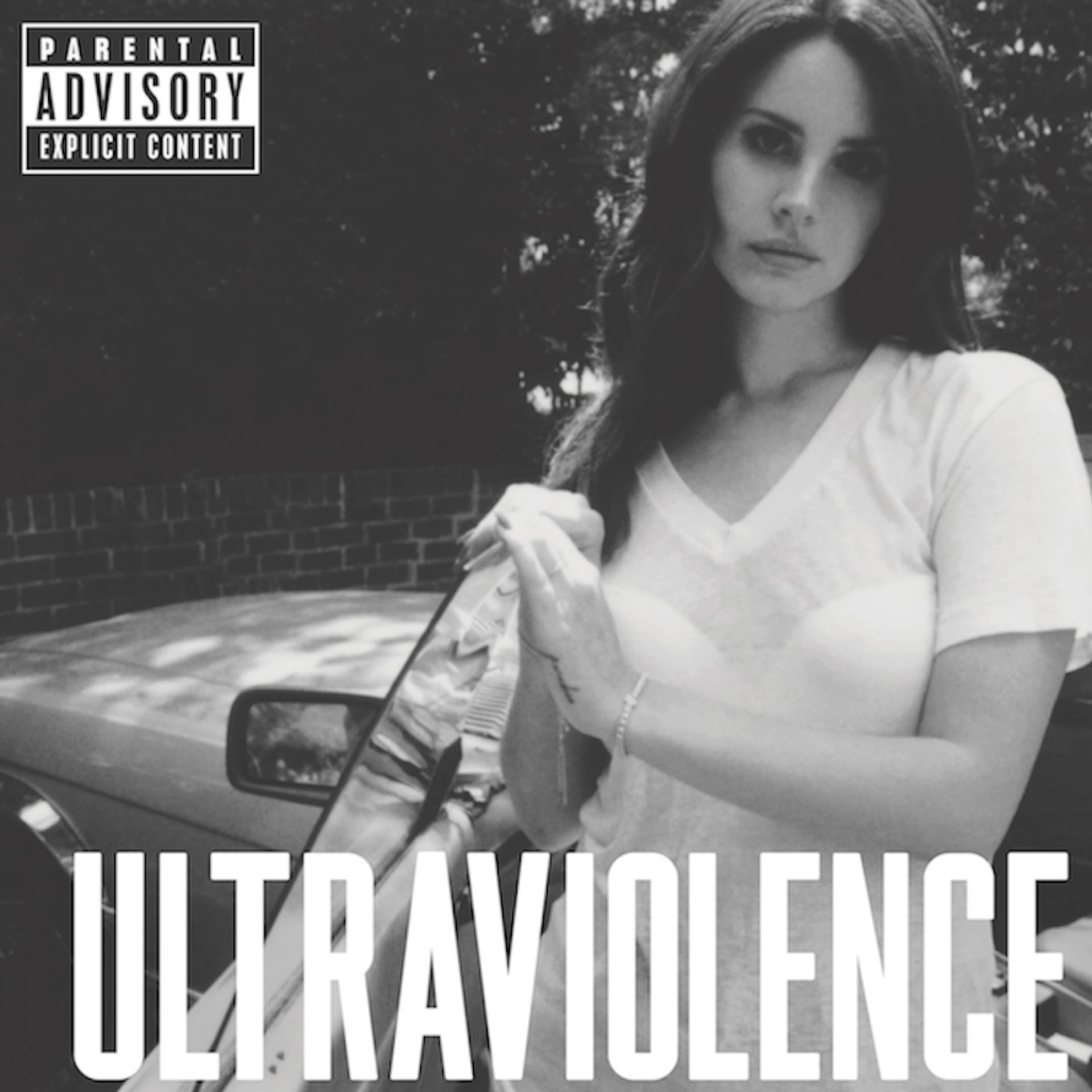

William Bennett and Lisa Blanning on Lana Del Rey’s Ultraviolence

Following their lively discussion of Lady Gaga’s Artpop last September, Lisa Blanning once again spoke with controvertial Cut Hands mastermind and Whitehouse member William Bennett—this time about Lana Del Rey’s current venture further down the rabbit hole of shifting pop identity on her new LP Ultraviolence.

Lisa Blanning: William, were you interested in Lana Del Rey’s music in the past? That is before Ultraviolence came out?

William Bennett: I had this superficial understanding of who she was. I originally assumed from the name—and this is an example of how you can project so quickly—that she was some sort of Cuban, South American songstress. Also echoing seventies porn star pseudonyms like Vanessa Del Rio, which is no bad thing. The name resonates in a way that it’s hard to imagine she’s of Scottish descent.

LB: It’s a memorable name.

WB: And it’s a powerful filter to how you experience music, I think, through a name.

LB: That’s interesting. Because obviously her real name Lizzie Grant is a completely different projection than Lana Del Rey.

WB: That’s right. And after getting familiar and after listening to Ultraviolence, I started exploring some of the early work, in particular the unreleased set of songs from 2005 recorded as May Jailer, and then she used her own name, Lizzie Grant. It’s interesting because I think people might say, “Oh, she would never have become famous if she’d been ordinary Lizzie Grant,” but I disagree with that. It would have just projected a completely different persona. And I think she’s interesting and charismatic and talented enough; very different to how Lana Del Rey feels, thematically, but I think still a great success.

LB: A friend sent me a blog post by this producer who had been brought in to provide early beats for Lana Del Rey before she got famous. It’s actually two posts: one right after their initial session and after she first blew up. He talks about how all of the elements of what we see now were there from the beginning, and he predicted from the get go that she could make it. So it seems like she had this purposeful direction to begin with before all of this; she had a sound, she definitely writes the songs, and she’s got a whole aesthetic that’s already been worked out, even before she started receiving major backing. I think that’s both interesting and cool. I haven’t actually heard any of the pre-Lana Del Rey stuff . . .

WB: Well, the Sirens set that I’m referring to from pre-2005 is very, very stripped down. It’s just her singing with acoustic guitar, which on the face of it, doesn’t sound too interesting. Yet it’s actually a very beautiful album and the songs work brilliantly. As an album to keep in one’s collection for a long time, I think it’s arguably better than Ultraviolence, funnily enough. For being so young then, it’s remarkably confident, and not just in a retrospective way. I think Sirens stands on its own merits.

LB: That’s one thing that you can tell all of her records as Lana Del Rey: essentially the songwriting is the same through all of them and then they’re dressed differently.

WB: Very true.

LB: I would say that Ultraviolence is my least favorite Lana Del Rey record. I have to admit that I’m not the hugest fan, but the Paradise EP I think is really good. That’s eight songs and almost every one is very good, whereas on her first album, Born To Die, I feel like there’s only a few good songs on there and there’s a lot of throwaway material. Paradise is a fully realized piece and it’s all one aesthetic, as well. I think the problem I have with Ultraviolence ultimately is the producer. I really don’t like the inclusion of Dan Auerbach, who is famous for working with The Black Keys. I feel that this actually takes away from her sound what makes her special. To me, it’s a big step backwards, although I understand how as an artist you want to try different things.

WB: I guess it’s a question of personal taste: What kind of dressing do you like with your Lana Del Rey? I agree with you, I personally don’t like this band-with-guitars-in-a-big-empty-room thing. I prefer the dark hip-hop, electronic style, which I think works really well with her music. There are moments on Ultraviolence where the songs are, for me, ruined by cheesy guitar solos played right over her voice.

LB: I agree, the retro rock production. For instance, there are two songs especially, that I really dislike. One of them, “Cruel World”, is co-written by the guitarist in her band, Blake Stranathan, and the other, “Brooklyn Baby” is co-written by her boyfriend, Barrie-James O’Neill from the band Kassidy. On the first album, the hip-hop leaning is the most obvious. In the second release, it’s this modern production that takes from hip-hop but isn’t really hip-hop, but is so rich and full, it makes it unusual. For me, it worked because she’s got an old-fashioned style of songwriting, but with the modern production it created a frisson. That’s lost now. There are a couple of tracks that have that on this new album, but all that mystery is lost. I don’t know if you noticed, but also on a couple of songs on the new album her voice sounds very thin and off-key, and that’s not how she sounds in any other context that I’ve heard her, including live. I feel like that’s a bad way to portray her.

WB: Going back to 2005’s Sirens, that stripped-down approach actually would work as well. Either it’s just her voice and acoustic guitar or the style on Paradise.

LB: She says she works with essentially the same team for both Born To Die and Paradise. For instance, Rick Nowels, Emile Haynie, and Dan Heath, these were names that appeared prominently on both of those releases. Nowels and Heath appear on the credits for Ultraviolence, but Haynie doesn’t at all. And Haynie was a producer that started out in rap music, he actually worked with Eminem and Raekwon and Cormega. He worked with all of these big rappers before he came to her. Auerbach is the major producer, obviously, and that sound really makes a massive difference.

WB: I agree. It might just be the influence of rock types she hangs out with including her boyfriend. Because we know that since the beginning her songs are similar in style and approach, maybe she’s not that invested in the actual production and leaves a lot of that to the people she’s hanging out with.

LB: It’s obviously pure speculation, but it’s a shame, because I feel there was something very special. But I still think she can definitely write a song, but I’m no longer interested in listening to it when presented as it is on Ultraviolence.

WB: In mitigation, I think the songs survive on Ultraviolence despite the production, as her personality shines through so powerfully that it could be dressed up in anything and it would still be quite affecting. A lot has been said in reviews about all these dodgy men referred to in the songs and, barring the bonus tracks, I don’t feel the main tracks on Ultraviolence are really about these men. They’re much more a vehicle for her own responses or narcissism, which clearly is what interests her audience, and me.

LB: Yeah, but if she didn’t portray herself as this Lolita/bad-girl figure but everything else was the same, would she still have the same draw that she has? Personally, I do think it’s a really interesting aspect to her persona, but I was trying to deduce what it was about her that made her of such zealous interest. Her fans are very passionate while other people are equally enthusiastic about tearing her down; she’s very polarizing. I think she’s got this really strong charisma, which I can’t really define except to say that it’s star power. My feeling is that she is very talented, but there are celebrities out there who are more or just as attractive and talented. But for whatever reason, she really captures people’s imaginations.

WB: This is the thing: She’s definitely anomalous in the modern era where there are so many of performers straight out of performing arts schools with everything’s so practiced, in terms of their interview technique, the way they look on stage, the way they sing their songs. It’s almost high-class karaoke we have now, where they say the right things, they do the right things, they sing all in the same kind of way.

LB: Right, where with her it doesn’t feel that way.

WB: No, she’s an original pop icon of an era that’s almost passed us. She’s unusual. She doesn’t fit with people’s expectations. We were talking before about her interviews and how jarring and clumsy they come across, which I personally find endearing. She’s not practiced. She doesn’t say the right things, which rubs people the wrong way because we live in an era where interviews are absolutely necessary for your career.

LB: I know what you mean, when she doesn’t say the “right” things, but having said that, I do think she has a narrative that she continues to push and is important to her.

WB: What do you think that is?

LB: I feel as though she’s really intent on making people think or realize, one or the other, that she hasn’t had a leg up, so to speak. She doesn’t want people to believe the accusations that she comes from a rich family. She’s also intent on telling people that she hasn’t had any sort of plastic surgery—although that blog post I mentioned earlier, that producer says her lips are definitely bigger now…

WB: I’ve seen pictures of her when she was younger and she does look very different. I think she was beautiful when she was a teenager and she looks beautiful now, and it’s not a big deal. I can also understand why people would be touchy about plastic surgery.

LB: It’s more what it signifies. The whole furor surrounding her in the beginning was this question of authenticity, i.e. the claims that she’s completely manufactured and the accusation of surgery is just another example of that. I think now that’s unimportant. But the focus of authenticity changes. Now it’s less about, “Has she been propped up by her dad?” who actually works in advertising and probably helped her promote her early on in the music industry—and more about, “Is she actually the wild child she portrays herself as?” And that she consistently refers to herself in interviews as. Because that portrayal actually makes the basis of so many of her lyrics, I would say there’s probably some truth in them.

WB: My base feeling with the whole issue of authenticity is that, as a fan, I care that it’s presented to me in a believable way. So I don’t care if it’s true or not, I just don’t want to know. It’s your job as an artist to give me your art in a believable way. There’s a music industry machine now that’s very effective at doing that. In rap and all kinds of music, your background is now really important to your credibility. I think she probably found herself in a tricky position where she started out her career, signing a deal for not very much money with the original record label, and then in order to make her career believable through Interscope, who are part of that machine I’m referring to, she’s having to rationalize that period of her musical career. Which may have been awkward for her.

LB: Yeah, I feel as though the question of authenticity leads you down a theoretical cul de sac where it doesn’t matter. And I agree with you that essentially people don’t care, and let’s use Rick Ross as an example of that—he portrays himself as a drug dealer in his tracks when actually he was a corrections officer who named himself after a famous drug dealer. We all know this but that doesn’t mean we don’t like his music or that he ceases to become popular. Maybe with Lana Del Rey, specifically, it feeds a really particular male fantasy, doesn’t it? More so than an artist like Lady Gaga.

WB: Absolutely. I think it’s interesting to compare her with is an artist like Beyoncé, who’s that typical I-woke-up-like-this flawless. Where she peddles this idea of perfection, everything being done the right way, a benign image of what empowered women look like: hetero, family-oriented, sexy but ultimately wholesome where it counts. I love Lana Del Rey’s open wallowing in daydreamy, suicidal ideation. I’m not qualified to say this and I’ll go out on a limb and say it anyway, I think it may speak better to many women’s experiences of being a woman—in ways where Beyoncé doesn’t.

LB: I don’t know if I would agree with that, as a woman. I don’t think she speaks to me so much as a woman, although I see how possibly she would. She’s definitely said some things that speak to me as a person.

WB: Can I give you an example? This song “Pretty When You Cry” from Ultraviolence, portraying a woman checking out the wreckage of a horrible face after or during crying is a powerful notion, and it’s something that you definitely wouldn’t expect in mainstream modern songs, these ideas of beauty in misery or tragedy.

LB: There’s a point you hit on that isn’t about womanhood and is actually about personhood, and that’s the real. That’s the thing about all of the dark things that don’t just happen but are within us and that we either choose to explore or we don’t. And she openly says that she wants to explore that side. And I think that’s the part that is really interesting about her. But that doesn’t have anything to do with being a woman, that just has to do with being a person that is willing to admit that shit exists. And also saying so in a pop context, which is usually a very safe, anodyne place.

WB: The difference here isn’t the fact that it exclusively happens to women, but in terms of its presentation. In other words, the voice that we get is typically one of the hetero, family-oriented, wholesome-where-it-counts. And Lana Del Rey is providing something that women may not commonly be exposed to, that kind of self-expression or communication. It’s a glorious outlet. You don’t hear often these things in the context of women, so if you’re listening to the radio and Lana Del Rey comes on, it speaks to them in a way the usual crap doesn’t.

LB: You’re obviously correct in that assessment, because apparently Born To Die has now sold seven million copies worldwide. We’ll see what happens with her next tour, I don’t think she’s at the stage yet where she’s playing stadiums, but that’s a lot of records. So, I suspect that she’s on her way to that level. And it’s interesting that she could get to that level when there does seem to be a tangible darkness to what she’s talking about.

WB: It’s remarkable how uncompromising the whole project is. And considering it’s selling these kinds of numbers, I think she’ll have quite a long successful career.

LB: I think the lucky thing for her is she’s one of those kinds of artists who will never be required to change her sound. I really do think she’s talented and I also think she possesses something unique, and she’s got charisma, but I also think her work falls a level short of being truly great. It’s strange because it’s obvious to me that she wants to reach these depths, but she does it in kind of a shallow way. I think she’s capable of recognizing that deepness, that resonance, but I don’t think she’s actually attained that level yet. A lot of that comes down to her lyrics, though. Conversely, that’s also what makes her unusual in the pop realm. Again, I think it’s the tension between those two things—her desire to reach the kinds of levels of the people she admires, like Allen Ginsberg and Lou Reed—and the affect of her music. Maybe that’s part of what makes her compelling as a character. Her words, I feel, are more interesting when she does this poetry in between songs, like she did in the “Ride” video and in Tropico, a short film that incorporated three songs from Paradise EP. A lot of the lyrics in her songs themselves are ultimately pretty shallow. Except for “Ride”, I feel as though that’s saying something big. When she says, “I’ve got a war in my mind.” That’s a line that really sticks out. So many of the rest of her songs are about being the object of male fantasy, and luxuriating in that role.

WB: Yeah, I actually thought about that. I thought it might be a deliberate process, because in some ways, the vagueness of the lyrics—if they were much more dense, like say Lou Reed, Leonard Cohen and so forth—it would actually detract from the power of the songs. Otherwise, the more meaning that can be taken out of it, the less detail there is, the more you can project your own personal situation into the song.

LB: That’s the driving mantra of pop music, isn’t it?

WB: Exactly. This is something that is interesting from the field of cold reading practiced by fortunetellers and so forth, that they can use detail that is essentially a “universal experience” detail. Typically, a medium for example might say things like, “I’m seeing somebody, his name begins with J. J, J, who could it be? Who do you know whose name begins with J? Is it John, is it Jimmy?” With a direct hit it can sound uncannily personal, “How did you know I have this friend named Jimmy?” Songs are most effective in my opinion when that happens, and it’s usually either something like that in a song, which seems to speak to us personally, or via the environmental association we had when we heard the song. I think that’s how a lot of music works and Lana Del Rey, consciously or not, achieves this extremely effectively with her songs. ~

Published June 26, 2014. Words by Lisa Blanning & williambennett.