“You’ve got to pay your dues”: Madlib talks to Thomas Fehlmann

Following the announcement of the upcoming release of a Quasimoto rarities record, we reproduce a conversation between the revered hip-hop producer, MC, and “man of few words”—he lets Lord Quas do the talking for him—Madlib and the Neue Deutsche Welle architect and member of The Orb Thomas Fehlmann. This feature is taken from the Winter 2012/13 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine.

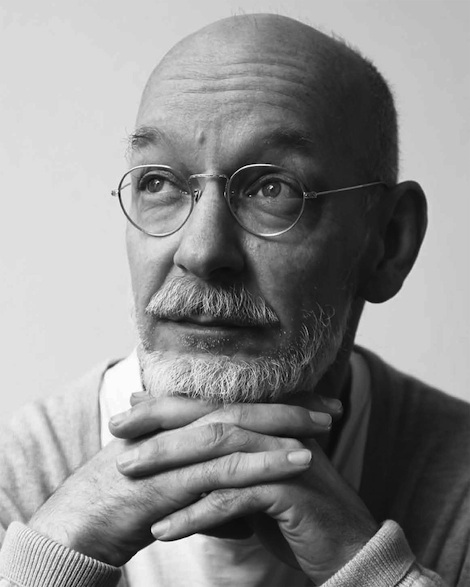

Los Angeles-based beatmaker and multi-instrumentalist Madlib is widely regarded as one of the most original producers in hip-hop. Born Otis Jackson Jr., the Stones Throw label vet and former Lootpack member has honed a jazz-tinged, sample-heavy sensibility that defined the genre’s underground offshoots in the late ’90s and early ’00s. An avid crate digger and a vocal proponent of sample source eclecticism, Madlib’s path has rarely strayed from the groove-related, and his most recent work with veteran krautrockers Embryo is no exception. In a rare conversation, the notoriously reticent musician opened up to Thomas Fehlmann of The Orb and Palais Schaumburg about collaborating with the late, great J Dilla and the joys of discovering German music. Main portrait of Madlib photographed in San Francisco by Mathew Scott, Thomas Fehlmann photographed in Berlin by Luci Lux.

Madlib: Thomas, just so you know: I’m a man of few words.

Thomas Fehlmann: The last big interview I read with you was in The Wire a few years back. My good friend and former fellow band member Moritz von Oswald was on the cover just a few months before that. Back in the day we played together in Palais Schaumburg. Have you heard the new album Fetch he did with his trio? It’s really impressive, very jazzy, electronic, and very eclectic.

M: No, I haven’t. I actually don’t know much about new music, really.

TF: Well, Palais Schaumburg is old school. And pretty experimental. Early ’80s. We started playing live again last year for our 30th anniversary. I played—and still play—live synth and trumpet through an echoplex. The lyrics are all in German and very Dada.

M: Oh, I’d love to hear it. Trumpet through an echoplex, huh?

TF: Yes, it’s pretty free, apart from an occasional riff, although our music is mostly structured around a danceable beat. It seems to me that generally speaking, European music is obsessed with rhythms in 4/4, particularly today’s dance music. Do you think this is a continental phenomena or what’s your take on straight rhythms?

M: Well, funk is 4/4. It’s so you can dance to it. Although, shit, I could dance to 5/8. It’s all music.

TF: I hear you. What have you been up to since coming to Berlin?

M: Just drinking wine, chilling with Embryo and relaxing. I’m sure you know that Embryo is a musical collective from Munich that started out in the ‘7os. They make pretty eclectic krautrock, working a lot with jazz musicians and world music and whatnot.

TF: Have you guys been rehearsing?

M: No, just listening to some of the stuff we recorded last time, around five hours of tape.

TF: But you’ll also be playing a show in Berlin later this year. I actually penned that into my calendar before I knew that I would be meeting you for this conversation.

M: Hey man, bring your trumpet to the show.

TF: How did you know about Embryo? Crate digging?

M: Actually from touring. I’d been coming out to Berlin since 2001, and I’ve been learning about different types of music. Krautrock is certainly one of my favorites.

TF: Have you checked out Can’s Lost Tapes?

M: Yup, I picked it up almost immediately when it came out. There are some absolutely brilliant tracks on there. Honestly, Can are one of my all-time favorites. I actually played with Jaki [Liebezeit] with the Brasilintime cats.

TF: He also has this brilliant project with Bernd Friedmann. It’s so cool that Jaki’s so persistent about working with all types of artists.

M: Yeah, he’s very open-minded.

TF: Have you gone record shopping in Berlin yet?

M: Actually, no. Nobody’s told me where the stores are at.

TF: Well, you should start with Hard Wax. It’s not your average shop. The people who work there and run it have very strong opinions about what they carry. There’s also a legendary cutting room there where they master the records for lots of international producers. Unfortunately, they don’t carry that much hip-hop anymore. . .

M: I never buy hip-hop records.

TF: They also have quite a selection of African music, which recently started to blow up a bit. This grew out of the whole reggae and dub wave, and it sits quite well with the broader stream of contemporary releases. I find some of it is very psychedelic.

M: I love psychedelic stuff. That’s my era.

TF: Is that what you grew up listening to with your parents?

M: My parents were incredibly open-minded. They had everything from James Brown to Kraftwerk, and I had a record player in my room, so I would always steal their stuff and listen to it on my own.

TF: You’re lucky. I had to fight with my parents to play what I liked and to get my turn at the record player. Eventually when they got a stereo, I was allowed to set up the old mono system in the basement for my use.

M: That’s how I first learned about music. Back then music was a different feeling. These days everybody follows trends. I honestly think things were far more open-minded back then. People tried harder, and there was more of a spiritual aspect involved . . .

TF: It’s maybe surprising, but I think music with a spiritual angle is the music that really endures.

M: I also like my music loose. Quantized is cool, but I also like that human feel.

TF: I think the humanness is what separates your productions from things done within the grid . . .

M: Well, I like that stuff too.

TF: I remember when I picked up the first Yesterdays New Quintet record—one of your many aliases—I was so impressed. I mean, a lot of people say they like jazz, but actually doing it is another thing. Of course, I’d been listening to you since back in the day with Lootpack.

M: It’s an honor for me to hear that. Actually, Yesterdays New Quintet was my first shot at jazz. Sometimes, I kind of feel like a musical schizophrenic, to be honest. But I think that’s probably not a bad thing.

TF: I know what you mean; trying to absorb all the magic stuff one is passionate for. The new Orb album we did with Lee Perry, The Observer In The Star House, was also a first for us in many ways. He actually spent a week with us in the countryside near Berlin. We had to be ready when he was ready to flow and that was basically always. He had a tremendous hunger for new beats. We needed to be fast, have all the machines and beats ready at any time. Lee also had a buddy with him, and he told us that usually after around two days, Lee gets bored with whatever he’s doing… but he stayed for the full week. This is the album [shows cover].

M: [turning it over] Ah, Steve Reich samples.

TF: Had to get permission for those.

M: Of course!

TF: As I mentioned before, I’ve been following you for quite some time. I decided to take a picture of all your records that I own. [showing collection pic] I’m not as prolific as you are but there are similarities, I also make lots of my music from my record collection, mostly older stuff.

M: Got to come back to stuff that people missed.

TF: I tend to treat my samples quite a bit, but it’s a similar flow in that existing music is the foundation and main source for the artistic result. That’s not to say that some of it can’t get pretty radical…

M: Even if it doesn’t sell, right? That’s some of the best stuff!

TF: When I see your work, I can look at it as if the idea of using your record collection to make music is a kind of conceptual art: the cultural output of society as the source material, put through the filter of your mind and your sampler. What about the other cultures that you explore in your music—non-Western conceptions of pop?

M: It’s all music that was done through records I bought—not visits to India or the Middle East or whatever. But I did manage to pick up the records from all over the world. The internet for me has been a help in finding material, but it’s actually something I just started using. I’m not constantly listening to streams or anything like that. We used to have tons of record stores where I live, but they’re disappearing one by one.

TF: Tell me about it! How important is the artwork for your records?

M: Well, it has to fit. A lot of the artwork just comes from pictures in my room or whatever. Like the Quasimoto album with the Frank Zappa bubble… This is stuff I look at all the time and surrounds me. I was living with Jeff Jank who does all the artwork, and we just listened to tons of Zappa.

TF: When I was a teenager I used to go to Zappa concerts when he was playing with Ruth Underwood and George Duke.

M: You got to love Zappa and Beefheart, The GTOs, Wild Man Fischer and George Duke… Zappa made me study all that stuff even more.

TF: Don’t forget Varèse! That’s the direction Zappa pointed me in.

M: You got to pay your dues.

TF: I think in Europe, there’s been resurgence in vinyl, amongst DJs, of course, but also people who love the object and its special sound quality. I see the whole numbering and signing thing as a part of that, which I know you’ve done. Is there a vinyl resurgence in the US?

M: Not that I know of. I mean, it’s still around and some people buy it, but not enough.

TF: You did it with the Medicine Show, too. Labels are becoming more like art galleries, encouraging their artists to put out stuff that’s really personal and unique, visually and sonically.

M: I think the art is as important as the music, to be honest. I don’t just download things. I want to know who played on a record, who produced it, where it was made… This stuff is important to me and always has been.

TF: So you don’t listen to contemporary music at all?

M: I do, but I don’t buy it. I’ll hear it when I’m in a club or whatever, but I don’t search it out.

TF: But there are musicians these days doing great things you just can’t hear in a club. It’s stuff that’s spiritual too but too experimental for the dancefloor, like Jan Jelinek or Daedelus, for example.

M: I like Daedelus, that’s my boy. But I have so much old stuff to discover I don’t know when I’ll have time to get to the new stuff.

TF: I remember reading in your interview in The Wire that you have all sorts of “future music” that’s unreleased. When are we going to hear that?

M: I don’t know. I don’t even know if I’m ready to hear it. There’s a lot of music I’ve done that’s gone unreleased: dubstep, synthesizer records, all types of different things, Cluster-like and beyond. I would say I’ve released around thirty percent of the music I’ve created.

TF: One thing I’m really curious about from a musician’s point of view is how you find the time to be in the studio and make so much music and still take care of, like, domestic stuff?

M: It’s not balanced. I’m mostly working in the studio. I mean, I have one at my house, but I’m usually in my bigger studio. I do what I need to do to feed my family, so they understand. It’s not really a balance yet, but I don’t see it as work. It’s music. Doing construction is work. What about you?

TF: I have to be able to let go to make good work. Forget about what’s going on in music, forget about my to-do lists. My mind and my environment have to be relatively in shape before I go into the studio.

M: Yeah, it’s easy to ignore everything, when your head is in the music. Even your health. It was the same thing with Dilla.

TF: Tell me about that. He’s regarded as one of the most important producers . . .

M: When he was alive, so many people seemed inspired by what he was doing. I heard Dilla everywhere, in so many different kinds of music. His influence was immense. He could do any type of music. I heard all sorts of stuff he didn’t release—electronic, Kraftwerk stuff… He was deep. I was lucky enough to kick it with him here in L.A. I guess he had to die for everybody to, you know, find their own way. It’s a weird way to put it, but that’s how it is. The music is so warm, precise and soulful. That’s how he lived. He’s like Bird and Coltrane, like Doom and… Doom.

TF: You’re one of the few people who’ve gotten access to the Blue Note archives, which you waded through to make Shades of Blue back in 2003. I always wanted to know what that was like.

M: It was fun. They have way too much stuff they should have released. The best records are still in the vaults.

TF: There are so many new things coming out of Los Angeles. I really like your brother’s work too, Oh No.

M: We actually just finished an album together.

TF: Really? That’s great news. I can’t wait to hear it. I’ve seen Oh No live a bunch of times. I actually just picked up his new record, Dr. No’s Kali Tornado Funk.

M: He’s a little beast. Both of us like looking all over the place for sounds. Really, you can find good things in every kind of music. I mean every kind, you know? You just have to look hard enough and have an open mind.

TF: In Germany we have a very broken relationship towards our cultural identity. Classical stuff here is more bourgeois. Then there’s the real folk music with accordions and all that. Some of it is impressive.

M: Everybody is one, we just live in different places. I’m ready to sample some Martian music, aliens and what not. I’ll perform for all Martians, you know what I mean? ~

See this article as it appears in our print magazine via Issuu.com below:

Published May 20, 2013. Words by Madlib & Thomas Fehlmann.